The college earnings premium is near record highs

It’s been a pretty solidly established fact by now, but in case there’s any lingering doubt about whether it’s worth it to go to college, here’s more evidence.

The college earnings premium—the ratio of earnings for those with a college degree to earnings for those with a high school degree—has reached historical highs in recent years.

In 2014, the median full-time, full-year worker over age 25 with a bachelor’s degree earned nearly 70% more than a similar worker with just a high school degree. Jason Furman, head of the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers tweeted out this chart illustrating the earnings premium after the July jobs report was released last Friday, citing findings from a July report by the CEA.

Over the course of a career, the median worker with a bachelor’s degree will earn nearly $1 million more than the same type of full-time worker with just a high school diploma, according to the CEA report which covers trends in student borrowing and repayment. The same type of worker with an associate’s degree earns a premium of about $360,000. (It does, however, take longer for some to break even on their college investment than others, as Goldman Sachs pointed out last year.)

“Higher education may be the single most important investment that young Americans can make in their futures,” the authors wrote. (The CEA report also touts President Obama’s PAYE plan which caps monthly student loan payments at 10% of discretionary income, and which the White House says is benefiting nearly 5 million borrowers.)

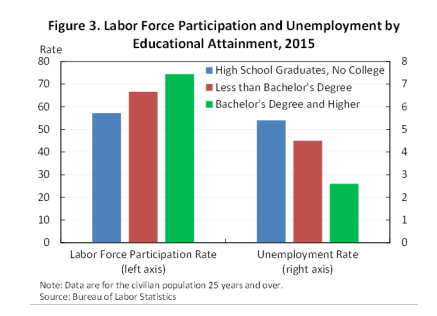

In addition to higher earnings, college graduates are also 1.3 times more likely to work than those with just a high school degree. The report cites BLS data showing that college graduates with “at least a bachelor’s degree participate in the labor force at a higher rate than high school graduates (74% vs. 57% in 2015) and also face a lower unemployment rates among those who participate (2.6% vs. 5.4% in 2015).”

And, by the way, in June Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce gave yet more weight to the college-is-worth-it argument with its report that found that out of the 11.6 million jobs created in the post-recession economy, 11.5 million went to workers with at least some college education. And of those jobs, 8.4 million went to workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Another bonus for grads: they have higher odds of moving up the economic ladder and experience “a wide range of non-economic benefits like health and happiness,” according to the CEA report, which cites past research.

Despite the stark difference in earnings and employment between the degree-haves and have-nots, the report delves into why some students, burdened by their student loans, don’t end up better off after college.

Here are 3 more takeaways from the report:

College returns vary and it’s especially bad for for-profit students

Overall, the financial benefits of a college education are high, but of course, it doesn’t work always work out great for everyone – particularly for those who attend for-profit schools.

The years following the Great Recession saw a spike in student-loan borrowing, driven largely by students attending for-profit and community colleges and by those from low-income families. The problem is that many of these schools “yield low or even negative returns, especially for students who do not complete degrees,” according to the study. Between 2009 and 2015, outstanding debt grew by 158% for community college borrowers and 142% for for-profit borrowers, compared to an overall increase of 107% in outstanding undergraduate debt.

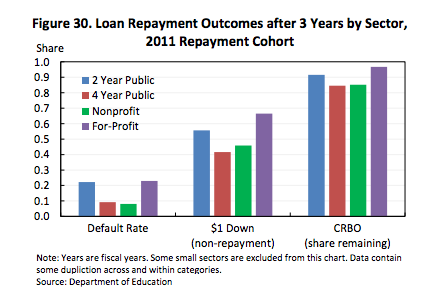

For a comparison, check out this chart:

After three years, borrowers from nonprofit and four-year public schools have paid down 15% of their original balance on the whole, compared with only 8% and 3% at community colleges and for-profits, respectively.

For-profit students, the CEA report says, are “more likely to be unemployed, to default on their loans, and to say that their education was not worth the cost.”

Size of your loan matters

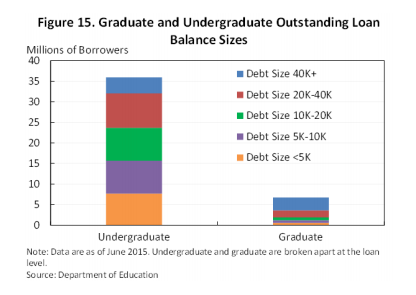

Outstanding student debt in the US has reached a whopping $1.3 trillion as of 2015. And although individual federal debt levels have been mushrooming and outstanding balances of $40,000 or more are not uncommon, there is a bright spot: the debt burden owed by the typical student is on the “modest” side.

As of June 2015, the majority of borrowers with outstanding undergraduate loans owed less than $20,000 (the average amount of undergraduate loans held in 2015 was $17,900); 42% owed less than $10,000; and only 10% owed more than $40,000, the CEA says. It’s typically graduate-school borrowers who have heftier debt loads: 43% owed more than $40,000 in graduate loans.

Dropouts fare worse

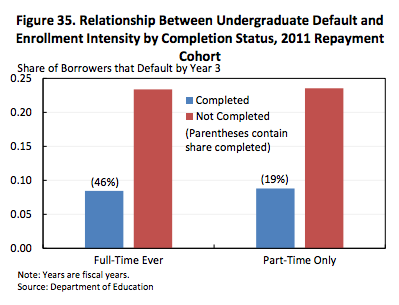

Who’s most likely to default on their student loans? According to the CEA, low-income borrowers, those who attend for-profit or community colleges, part-timers, and especially, those who don’t finish their degrees.

Defaults are concentrated among borrowers with small-volume loans, in large part because these borrowers are less likely to have completed their degrees. Loans of less than $10,000 accounted for nearly two-thirds of all defaults for the 2011 cohort three years after entering repayment. Loans of less than $5,000 accounted for 35% of all defaults.

The report found that among undergraduate borrowers who entered repayment in 2011, those who didn’t finish their degree defaulted at a 25% rate after three years, compared with just 9% among those who did complete. And after three years, 58% of degree-holders had paid back at least a dollar of their loans, contributing to a 14% decline in their original balance. Of those who didn’t finish, only 39% of had paid down a dollar of their initial balance and 94% of their original balance remained unpaid after three years.

Lisa Scherzer is an editor at Yahoo Finance. Read more:

Companies are making big changes to their parental leave policies

How your brain gets in the way of making smart money decisions

Aging parents: Your adult kids aren’t total ingrates like you think they are