Congress votes to roll back internet privacy protection

Update: On Tuesday afternoon, the House approved the bill to stop the FCC from enforcing its internet privacy rules. The bill now goes to President Donald Trump for approval.

The House was expected to vote Tuesday on a bill that would stop the Federal Communications Commission from enforcing rules that would stop your internet service provider from tracking your browsing behavior and selling that information to advertisers. The Republicans backing this measure would like you to think that it’s a pro-competition move that will only improve your internet experience.

But a closer look at this issue should leave you skeptical of that sales pitch.

Yes, your ISP might want to snoop on you

The text of S.J. 34, a resolution that passed the Senate by a 50-48 vote last week, is stunningly concise by legislative standards: “Congress disapproves the rule submitted by the Federal Communications Commission relating to ‘Protecting the Privacy of Customers of Broadband and Other Telecommunications Services’ (81 Fed. Reg. 87274 (December 2, 2016)), and such rule shall have no force or effect.”

The FCC passed those rules in the final weeks of President Obama’s term after establishing a legal footing for them with the net-neutrality rules that prevent internet providers from slowing or blocking legal sites or charging them for priority delivery of their data.

Those open-internet rules put internet access services in the same “common carriers” legal category as phone companies and therefore subject to the same longstanding privacy principles. That, in turn, led to the process of writing these rules—although they have not yet gone into effect.

Not hypothetical

It also followed two notable examples of ISPs selling data about their users. Verizon (VZ) attached a “supercookie” tracking bit to the unencrypted data of wireless subscribers, then took months to offer an opt-out. AT&T (T), in turn, required subscribers to its gigabit fiber-optic service to opt out of an “Internet preferences” tracking scheme — although that tracking at least yielded a big discount.

This is not a hypothetical threat, much as the net-neutrality rules followed years of bluster by Big Telecom to charge sites for the privilege of using their pipes.

Trade groups like the wireless association CTIA and the cable group NCTA say they will do no such thing, declaring their commitment to protecting customers’ personal information.

Those organizations and others released a list of privacy principles in January that include getting customer permission to use “sensitive data” (the Federal Trade Commission’s term for details you could use to steal somebody’s money or identity) and giving customers a chance to opt out of the marketing use of “non-sensitive” information.

The companies listed on it include AT&T, Charter (CHTR), Comcast (CMCSA), Optimum owner Altice USA, T-Mobile (TMUS) and Verizon — but not Frontier Communications (FTR), Sprint (S) and U.S. Cellular (USM), among others.

Google and Facebook aren’t the same as your ISP

Telecom companies like to complain that web companies don’t operate under the same regulations. That is true. Ad-driven firms like Google (GOOG, GOOGL), Facebook (FB) and Yahoo Finance’s corporate parent Yahoo (YHOO), benefit from a more lenient environment.

“The concern is really one of making sure that consumers have a consistent online framework,” said NCTA executive vice president James Assey on a conference call with reporters Tuesday.

But those web firms also occupy a different position relative to customers. You don’t have to use Facebook or Google, nor do you have to use them all the time. When most Americans are limited to the cable company for the fastest connection, leaving that firm is a lot harder.

The increasing use of encryption by websites does help secure their link with your browser and limit your ISP’s ability to spy on you. But the ISP will still see the domain names of sites you visit — which, if they correspond with political parties, pharmaceutical firms or advocacy groups, can still reveal a good deal about you. Dodging that scrutiny would require you to use a virtual private network service to encrypt your entire connection.

Facebook and Google also let you see, edit, delete and export most of the data they have on you. They were also documenting government requests for consumer data in “transparency reports” long before telecom firms picked up the habit.

Congress could fix real problems instead

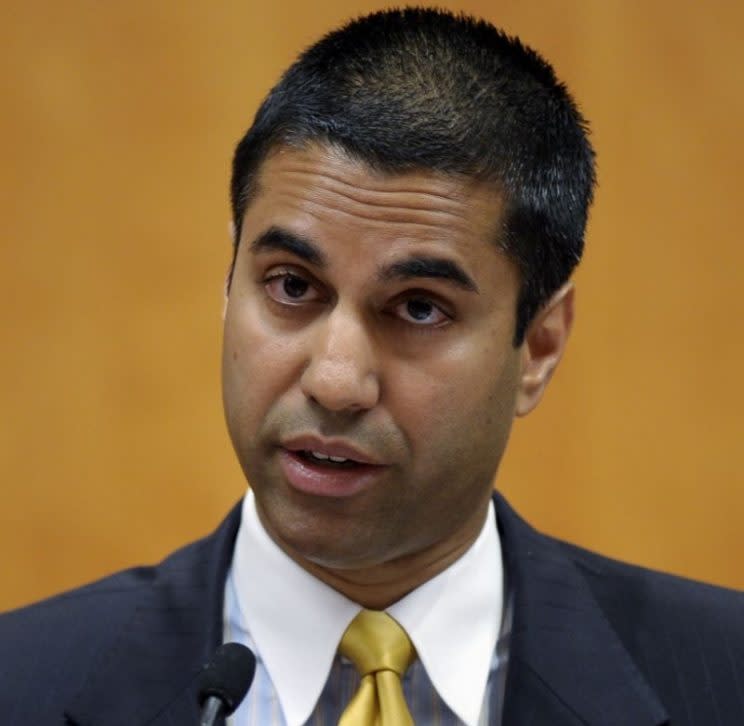

The rush to undo the privacy rules looks especially unseemly given that FCC chair Ajit Pai has already led a vote to stay implementation of a subset of them requiring ISPs to disclose data breaches promptly. And as participants on that media call emphasized, the FCC will retain its underlying authority even if the impending set of rules gets cast aside.

Meanwhile, let’s look at the actual tech-policy problems Congress has failed to solve. It still hasn’t reformed the Electronic Communications Privacy Act, a 1980s relic that says cops don’t need a warrant to peek at email stored online for more than 180 days (fortunately, major webmail firms insist on one). A “Dig Once” bill could make expanding broadband infrastructure part of federally-funded transportation projects, but Congress continues to dawdle on that too.

I agree that it would be nice to have some federal standards for privacy that would apply to both ISPs and web firms. But the idea that this Congress will pass a comprehensive privacy bill is laughable.

Passing big tech-policy bills just doesn’t seem to be Congress’s thing anymore — the Telecommunications Act of 1996, the last major one, is now old enough to drink, and it seems in zero danger of being replaced.

So if the House does vote to shut down the FCC rules, the realistic alternative isn’t some sweeping privacy law like the European Union’s forthcoming General Data Protection Regulation. It’s hoping that publicly shaming companies will curb the worst abuses.

(Disclosure: Verizon is currently expected to purchase Yahoo Finance’s parent company Yahoo.)

More from Rob:

Google’s chief internet evangelist seems nervous about Trump’s tech policy

Venture investor on Trump: ‘We are in an absolute unmitigated crisis’

The real lesson of Wikileaks’ massive document dump — encryption works

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.