‘The Fall’ Season 3 Postmortem: Creator Allan Cubitt’s Deep Dive on Spector and Gibson’s Fates

Warning: This interview about the Season 3 finale of The Fall, “Their Solitary Way,”

contains spoilers.

It’s been a month since the third (and at least for now, final) season of The Fall aired its finale in the U.K. and hit Netflix. Fans now know that Paul Spector (Jamie Dornan), the Belfast Strangler, is dead, having committed suicide, and our hero, Detective Superintendent Stella Gibson (Gillian Anderson), lives to fight another day. Yahoo TV spoke with creator/writer/director Allan Cubitt about the finale’s key scenes, Paul’s amnesia, Stella’s revealing conversations with Dr. O’Donnell (Richard Coyle) and young Katie (Aisling Franciosi), and that parting shot of Gibson.

We’ll focus on the finale, but to begin: When did you realize that Paul claiming he couldn’t remember the years after 2006 would be the framework for Season 3?

Allan Cubitt: It was always in my mind when I was looking at what kind of trauma he could suffer as a result of the shooting [in the Season 2 finale] and what would be good to complicate the situation for Gibson. I suppose it was partly finding a way of keeping [Gibson and Spector] apart again. Finding that there were once again people interposing themselves between her and him — in this instance, medical professional people. I was interested in the professional reaction to him, given what he stands accused of and given who he might be. [The doctors and nurses] don’t know; he hasn’t been tried and he hasn’t been convicted. I was interested in the tensions it would create — trying to save the life or treat this individual who, all the signs are, is responsible for terrible, terrible things.

Reading reviews of the final episode, and just having conversations with friends, it’s clear people have different opinions about whether Paul’s amnesia was real, in the end. I’m guessing that you love the fact that people are debating that, but how did you view it?

It’s not something I want to pronounce, because I do like the fact that people are debating it. It seemed to me that if I resolved it either way by revealing that it was completely fake or by suggesting that it was entirely real, it would be a compromise, it would be a cop-out in some kind of way. I think the ending is so self-destructive. It’s so full of the kind of destructive nature of his character that there’s no doubt that there’s continuity to his character, do you know what I mean? It’s not as if he’s a changed person in that regard, and in part it’s playing off those aspects of his character that always were easier to contemplate — his intelligence or his apparent charm and so on, and how those come to work on other people.

I think one of the reasons why Dr. Walden is there to say to Dr. Larson, “Look, it has to be malingered” and why Gibson continues to say, “It has to be malingered” is because that’s partly the conclusion that you need to reach. His symptoms are impossible to fake when he first comes around, so he’s genuinely confused, and there may possibly be some foundation to amnesia that’s real in the first instance. But my feeling is that he builds on that. As people keep saying, “If it’s not entirely malingered, then it’s probably exaggerated, and he’s using it toward his own ends.” I think that’s probably the case, because as I say, in the end, he behaves in a way that fulfills his own sort of prophecy in Season 2, where he says to Katie, “Serial murder is a form of slow suicide.” He says to her, “Not my style,” but I think anyone who embarks on crimes of that nature knows that chances are they will perish as a result of it.

When they decide to suspend the final interrogation scene, there’s that great moment when Gibson is staring at Spector with a look of satisfaction, and Spector smiles. You could read that smile as either, “You got me, I’ve been faking, but I’m figuring out how to attack you now” or “Fine, I’m going to give in — you think the worst of me, if it’s really in there, I’m going to let it out now.”

Yes, I think that’s absolutely right. It sort of wants to be open to interpretation because, I think, what I’m trying to reflect is a kind of reality whereby these things are never clear-cut in the real world either, how far someone is feigning. I mean, it’s partly the conclusion that they sort of move toward in The Sopranos when Dr. Melfi decided that she wasn’t going to treat Tony anymore on the basis of some research that suggested that sociopaths actually enjoy the talking cure because it was a possibility for them to rehearse their responses to situations as if they were a normal person. They cry crocodile tears. The thing that people consistently say about these individuals is that you might see something that looks like remorse, but it’s more likely to be remorse that they’ve been caught than it is remorse for their victims. It’s interesting to me that those things are open to interpretation, and that’s the way it should be, because the reality is that you can never know for sure and so you’re always trying to interpret the signs, you’re always trying to make sense of the thing that’s placed in front of you, working off the best evidence you can. I’m glad you picked up on that moment. It’s a kind of a key one, you’re right.

Related: On the Set of The Fall: Gillian Anderson and Jamie Dornan Prepare for a Final Showdown

Some people think the level of brutality of Spector’s physical attack on Stella is evidence that he had been faking, because there was so much rage. But, on the other hand, this woman had just detailed the sexual abuse he remembers suffering at the orphanage and told him what kind of attention-seeker he’d become and to grow up and accept responsibility for his actions. So again, he could be thinking, “Fine, I’ll be who you say I am.”

I’ve always wanted to suggest that the people who perpetrate crimes of that sort are driven by a fantastic level of rage, and that’s something that’s been a part of him and was released in Season 1 when he’s attacked by Joe Brawley — his rage was off the charts. We approached the attack on Gibson on the basis that he wouldn’t stop attacking her unless he was stopped from attacking her. There was no sense in which he was teaching her a lesson or something; he would kill her if he was allowed to. But yes, he has, just before that, said, “I’m fascinated by this person. I want to learn who the real Paul Spector is.” The look that he gives her feels as if he has been defeated in some kind of way and that he’s going to react in a Spector-like way, which is to unleash the rage that has obviously been part of his life ever since childhood.

The look that Spector gives right before he attacks Stella is absolutely chilling. Did it take a lot of takes to get?

No, it was something I saw Jamie do on that shot, as it were. There’s the look beforehand, but there’s also that look that he gives as she walks, where he follows her with his eyes briefly. I knew I had both of those things, and I didn’t ask Jamie to do them, that’s just what he did in the moment. Jamie is, I think, a brilliant actor, and he very much finds those moments for himself. The look he gives there is really stunning because it’s complex — he is both defeated in that moment and defiant in that moment — and it is chilling for the coldness, the contempt.

But, of course, he’s fueled by a massive amount of self-contempt. Good actors can make things self-reflective. It’s like in the first episode [of Season 3] when Gibson talks to Tom Stagg in the corridor about the best way to approach Rose, the best way to approach a woman after a sexual assault of some sort, and the brilliant thing about Gillian is that she brings it back to Stella in some kind of way, so you get the sense as she’s doing it that she’s really talking about a time in her life when she needed kindness and tenderness and understanding and didn’t perhaps get them. I think they’re both actors that have the capacity to do that, to make it self-reflective, to make you think, “Oh my God, she’s talking about herself.” That’s a great quality.

When, in your mind, did Paul decide to kill himself? Was it sealed when Dr. Lawson (Krister Henriksson) told him that he was treatable but not curable, that he’d need to learn how to experience feelings and not act on them?

It’s an interesting question, isn’t it, because as I say, I think it’s an inevitable end for him. I wanted the audience to think that he might be in the process of trying to get out. In the initial visit to Larson’s office, to find Larson’s office dark and locked, it’s not completely clear, and then of course Larson walks back into the trap, as it were. Spector had seen the plastic bag when Larson stowed his keys away in the airlock, and so he’s got it in his mind … Yes, there comes a point where he thinks the game is up. I’m aware of the fact that, again in reality, quite a few of these individuals do, at that point in time, take the opportunity to take their own life because they want to maintain some kind of control, even if it’s the ultimate self-destructive control. The desire to control the situation, the desire to undermine any sense of Gibson getting satisfaction. Gibson is desperate to see justice done, she’s desperate to see him go to trial, to be convicted, to spend the rest of his life in prison. And like I say, quite a few of these individuals say, “You’re not going to have that satisfaction” — a bit like deciding to take Gibson to see Rose at the end of the second [season], it’s another attempt to regain control of his life. Even if in this instance it’s just his death, he’s in control.

It’s somewhere around the Larson conversation that he knows it’s the end of the road for him in some kind of way, and I think it possibly comes in the “man of double deed” and “death and death and death indeed” moment. It’s a sort of death sentence on them both, him and Mark Bailey, though of course Mark Bailey doesn’t know that. So it’s one last revoltingly destructive act, both in terms of the callousness and pointlessness of the murder and then his self-murder as well.

Why does he strangle Mark? Knowing Mark’s backstory with his sister, was there a part of Spector that thought Mark deserved to die, or was he just an easy target to help feed his demons one last time?

I think it’s both of those things. I think on the conscience level, it transgresses Spector’s view of children — the age of [Mark’s] sister was crucial to Spector’s understanding of it. But that ultimately is just another act of, as you say, feeding his own demons. Again, it’s defiant. It’s going out with a “bang” basically, and not a whimper, to paraphrase T. S. Elliot. It’s an attempt to do that, but it’s futile and hideous as well. So it feels fitting for Spector to make this last grandiose act, but it’s a shabby and disgusting one.

There is a moment when Paul is dying where he seems to reach up as if he wants to try to stop it.

I think that was precisely it, not that he would necessarily want to stop it, but again, you’re feeling that sense of, “Oh, my God.” I suppose I feel that for a lot of people, when they’re taking their own life, there must be that moment. People who’ve survived suicide attempts have often reported that in that moment they want to live.

From the very beginning of The Fall, one of the things that I was trying to write about was the will to live, which I think is incredibly strong in people. I’ve talked about this before, but one of the reasons why I had Sally Ann as a neonatal nurse and had the idea that there would be a premature baby in the drama at the beginning, was to try and convey to the audience that, for the most part, all of us have a real will to live, and that that’s apparent in the baby that’s 21 weeks old who has got a powerful urge to live. I was trying to contextualize the idea of someone who then chooses to take other people’s lives: What it is that you’re doing at that point, how horrifying it is that you would snuff out someone’s life. You feel you have the right in some kind of way, or you’re driven to an act of that enormity. I wanted to try and capture something that conveys the horror of the idea that you could end someone else’s life — and that someone would know their life was ending in this sort of squalid and horrible way. So I suppose even Spector has a life force, from that point of view, that might have been struggling against his own actions. I guess that’s why he does the bag and the belt and goes to those lengths to stop himself from saving himself, as it were. He’s beyond redemption.

Related: The Fall Postmortem: Creator Allan Cubitt’s Deep Dive Into Season 2

There was some conversation after the finale aired in the U.K. about the depiction of Paul’s death. To me, when you have a character talking about “a visible and an invisible world,” you need to show the reality of that moment.

I think so. I don’t know how you would do it otherwise. One of the things that we’ve always been committed to in The Fall, and I hope this came across in the medical stuff, was to try and make it as real as possible. Obviously, there are ways in which you cut around that and cut away from it, and you don’t want it to be overly graphic and so on, but I think it could have been deeply unsatisfying if you didn’t have a sense of what he was doing, or how he had done it. If you simply came back to find him dead on the floor, it could have been really quite anticlimactic. But also because, as I say, it’s a squalid ending, I didn’t push it. I’ve seen deaths of that sort before where they concentrate on the fact that people urinate and defecate and all the rest of it; we didn’t do any of that. It was trying to address the reality of the situation, but I don’t think it was especially graphic compared to some of the other things I’ve seen in other dramas across the years. But it was shocking, I think.

You’re also weaving that Spector sequence with Stella’s conversation with Katie, as Stella’s trying to convince her to fight for herself. That was surprising, to see Stella open up and reveal more of her own backstory about how she, too, cut herself after her father’s death.

Right from the very beginning, I’d always seen Gibson as an enigmatic character, someone who reveals herself only little by little and slightly reluctantly gives up any of her own personal details. She’d hinted at it at the beginning of the second season by saying to Annie Brawley, “I once found having a band around the wrist and flicking it helped me, you might find it helps you.”

She goes further than that in the conversation with Katie, but I think that’s because I wanted her to reunite with the feminine side of herself, if you like, that she’s at times had to batten down. Particularly in the third season, it’s been eating away at her — it happens when she’s watching Sally Ann, and it happens when she goes to see Olivia in the hospital — so it’s something that’s coming to the fore in Gibson. That was a conscious and deliberate emotional arc for her in the piece. She’s operating, as she says to Ferrington, in a patriarchal, paramilitary organization, and that’s the world in which she’s chosen to work for all kinds of really quite powerful reasons. Right from the very beginning my idea was always that she has a particular interest in protecting and saving female lives. So the focus across those seasons began to narrow down to Rose and to Olivia and ultimately to Katie.

Now Katie, or Sally Ann for that matter, is not someone she had taken a particular interest in prior to that — seeing Katie as someone who was acting out in an adolescent kind of way and was basically creating problems. But there’s something about the self-harming that strikes a chord with Gibson whereby she feels that Katie is someone who can be redeemed. I suppose what I was going for, without it being simplistic, was the idea that Katie stands a chance of surviving. Just as I think Olivia stands a chance of surviving — that last scene with Olivia is supposed to do something of a similar sort. I wanted Gibson, basically, to be talking to Katie at that point more as a woman, rather than as a police officer or someone with that kind of world experience, and as a corrective to what it was that Spector represented and stood for throughout the course of the drama.

Related: The Fall Star Gillian Anderson Takes Us Inside Stella Gibson’s Mind

I’ve always had this notion that it really is about the power of love. There’s scenes right from the very beginning [of the series], the scenes with Sarah Kay’s sister or Sarah Kay’s father are always the ones that I would find most moving in terms of writing them — the sort of sense that people are connected to one another, they have loving relationships and those loving relationships are the things that allow us to survive. Bit by bit, we begin to understand that Spector’s been starved of those loving relationships at a crucial, formative time. What Gibson is saying [to Katie] is, “Look, we both lost our fathers and that’s traumatic to us, but we were loved. We were loved when we were little. We were loved and supported, and that gives us strength.” And of course by implication, that’s the strength that Spector doesn’t quite have. Which is why even Olivia might survive, because she has actually been loved despite the terrible destructive nature of Spector’s influence on her life.

It seemed to me that it was where the heart of The Fall lies, and it’s also that corrective to what it is that Spector’s doing, which is this extremely masculine, destructive behavior — which is, as I say, a kind of male response to powerlessness, a deep and abiding rage, for some men. What Gibson’s talking about is being creative and nurturing and saying, “You won’t get any of that stuff from him. You need to put him out of your mind because he won’t support you, and he doesn’t love you, and he doesn’t even know you exist, he doesn’t care about you at all, and it’s crazy that you have any vested emotion or investment in him.”

Another revealing scene was when Dr. O’Donnell sat with Stella in the hospital and began asking her questions. I loved the way they played that.

It’s quite an interesting thing to me that in myth, there’s quite often what is sometimes seen as a kind of campfire scene after an ordeal. If they survive that ordeal, there’s a scene of regrouping, and it’s often a downbeat, quite quiet scene. So you’ve had the brutality of the attack on her, and then in the middle of the night, someone pays a visit and it doesn’t advance the plot [laughs], it’s just a character moment.

I was conscious of the fact that I wanted there to be some good men in The Fall. And O’Donnell might be a little bit arrogant and a bit full of himself, but he’s definitely a good man. And Larson is a genuinely beautiful man, I think. I just thought it was ironic and it amused me, the idea that Gibson would reveal more of herself in terms of personal details to someone who is in some ways a complete stranger than she had across the entire three seasons thus far. I found that enjoyable and I thought rightly that they played it very well. They had a bond there that was two professionals who do these fantastically difficult jobs and they do them with great commitment and at some personal cost. I think if he’s a full-on A&E consultant, then there’s no doubt that by the time he’s 40, you start to think, “Oh my God, there must be some other way of making a live.” Because it’s exhausting and demanding. I have massive respect. I had a really brilliant A&E consultant who worked on the series with me, and just the times when he would text me, “Oh, I’m at work,” and I would hear bits of local news, like someone being attacked with a samurai sword or something, and then I’d talk to him and he’d say, “Yeah, he came in and his arm was severed and we couldn’t save …” It’s extraordinary that people are doing that sort of thing all the time, making an attempt to save people’s lives regardless of whether they’ve been stupid, or whether they had done something daft, or if they’re reprehensible characters.

He harks back to that idea that, during the troubles [in Northern Ireland], you could have someone who’d set a bomb and blown themselves up and blown up other people as well, but you’d be treating people, as he says, according to their clinical needs, not according to your attitude toward them or your moral judgments about them. I thought that was interesting.

Their conversation is also nice because he asks Stella if she likes flowers, and we hear she does, and then when we see her return home to her flat at the end of the finale, she’s brought some with her. Was that always how you imagined the final shot of Stella — returning home alone, drinking wine in front of the flowers she’d abandoned when she left for Belfast, avoiding opening her mail?

The thing I didn’t get to shoot was her stopping at a delicatessen and buying the flowers, and so someone said to me at some point, “Who gave her the flowers?” [laughs] I was like, “It was just I never managed to shoot the scene where she bought them.” So, no, they hadn’t been sent by Spector or something. But yes, just a little bit of beauty, I suppose, a little bit of “and then life goes on” kind of feeling. Just positioning her so that hopefully you’re thinking what a traumatic journey she’s been on and yet she’s still standing. “She’s my hero, and she’s still there.” It’s a hollow victory to be sure, but she survived. As she said to Rose, “You survived. That’s what’s important is you survive.” How people cope with trauma is again one of the things The Fall is about: You go through traumatic events and it’s so important how you seek to deal with those traumas, and who can deal with them and who can’t. Again, she’s saying to Katie, “You can deal with these things if you get loving support from the people who really care for you, but you can’t survive traumas otherwise, I don’t think.”

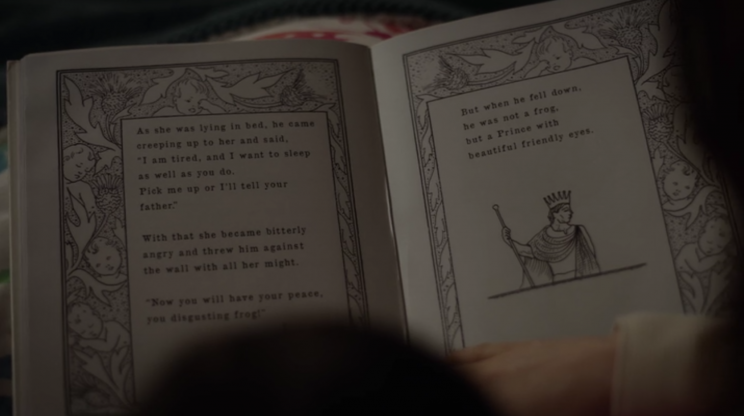

You mentioned Rose. There’s that scene with her reading the Grimm Brothers’ The Frog King to her daughter, with the princess throwing the frog against the wall instead of kissing him. How should we interpret that moment?

I’m one of those writers who finds a resonance and enjoys it. I’m a conscious artist, if you like, but at the same time, I like what happens if you just set something up to resonate and you leave it for people to interpret. Partly, it’s got to do with Rose has survived and her daughter has not lost her mother. They’ve got that bond, and that bond will mean that maybe Rose will get over what she’s been through but also her daughter will grow up loved and supported by her parents, and particularly her mother in that instance. But yes, it is that inversion, it is retelling some of those kind of classic tales from a more feminist, more female point of view.

I read an interesting deconstruction of “Blue Beard,” which applies well. At the end of that, the person who’s naïve has to gain knowledge and realize that this man is essentially a serial killer, as it happens, but in the story, she’s saved by her brothers just in time. But of course you can view that as being actually her growing on the forces of her own animus, you know? It’s finding those strengths within you. One of the things The Fall has always been about for me is Spector as a sort of dark intruder represents all our fears about what might be out there, but you have to balance that with the bravery to go out into the world and achieve things in the world. So she’s saying essentially to her daughter, “You can’t be naïve about this stuff. There are dangers out there, and you need to recognize them. Not because you want to spend your life cowering in fear, the reverse; because you need to properly integrate those fears to make you a stronger person who understands that there is a shadow side to life.” The fairy tales are all very strong in that respect, and it seemed like a nice idea given the mythic quality. [Laughs] One of the things I’m always trying to do is to make a story work with the power of a myth. Gibson’s been on a quest: She leaves the normal world and she goes into an abnormal world and she brings hope to some people and she, basically, survives. She comes through it, and there are lessons learned, and some lives have been touched along the way. Some healing can be done, so let the healing begin, I suppose, is partly the idea.

I also wanted to ask about Assistant Chief Constable Burns (John Lynch). The amount of drinking he was doing, and the way he yelled for DCI Eastwood (Stuart Graham) to get his hands off of him when Burns went after Spector following Stella’s attack, made me wonder if there was more at work there than Burns simply having investigated the pedophile Father Jensen.

It does feel like that. I think his investment in that is more than just a police officer who was traumatized by what he discovered on the arrest. I think it’s a police officer who’s had some history of abuse himself. The “get your hands off me” could just be a rank thing, like, “I’m your superior, how dare you touch me,” but because John was in tears when he said it… I think he’d got himself into a place whereby the torch that he’s carried for Gibson, which might be even the reason why he brought her in, in the first place, has gotten nowhere; he’d been to see Father Jensen [in jail in Season 2’s “The Perilous Edge of Battle,” asking for information about Spector] and had found that a futile and painful experience; and he’s ridden with guilt about things like that happening in the Catholic church and him being a Catholic, which is not to say it doesn’t happen in every other kind of church as well, but you know what I mean. Of course, Gibson’s reply to that would be, “Well, you have these ‘boys only’ clubs, then these things are going to occur.” But I think you’re right: his ultimate demise would suggest that he’s had some experience or abuse that goes beyond just arresting a pedophile and hearing the horrors.

Also, I was playing around with the idea that anyone who was a police officer in Northern Ireland through the troubles has been traumatized, and it’s a question of how they deal with it. They’ve seen so much carnage, so much death and destruction, as a younger police officer. I had a speech that he made about his past and how he got into being a police officer and the implications for his family in becoming a police officer as a Catholic, but I ended up taking it out. I don’t think I achieved it particularly well, so it ended up hitting the cutting room floor. But yes, a sad arc to Burns’s story. [Laughs]

And Anderson’s arm will be okay?

Ah, poor Anderson, yes it is. Yes it is. I don’t think it’s the end of his career.

I’ve seen you say that you’d be open to doing more of The Fall in the future, but that you have other things that you may want to pursue first. Is there any update on either end?

I don’t know at the moment, really. I kind of positioned it with Gibson so I could [do more], but I would need to have — and I don’t think I do have at the moment — a compelling story that I want to tell. Some of the things that I think about as potential stories, I feel like I’ve already covered some of the ground through Spector. Some of the issues, for example, surrounding criminality which are about childhood, about some of the dysfunctions and things that lead people to behaving in anti-social ways, so right now I’m not chomping at the bit to write another crime story, to be honest.

I’ve been working on a play at the moment. I’m adapting a dark and intense novel by a guy called Eugene McCabe, [Death and Nightingales], which is set in County Fermanagh, so it’s another Northern Irish project but in the 1880s. That’s exciting. It’s a powerful, slightly Gothic kind of love story. I have a lot of ideas in the early stages of developing which would allow me to try and do something a little bit different again, perhaps with TV drama. I think a lot of television is based on other television programs, and I think it’s incumbent on us all to try and come up with things that don’t feel like that. The best shows feel fresh and original in some kind of way and you don’t think, “Oh, I’ve seen all this before.” But there’s a lot of telly that you watch where you think, “I’ve seen this before.” I have a particular bête noire which is characters who are talking in a kind of TV language rather than having a psychological truth to them. I like things to be about something, and not all TV dramas are.

To that end, is the message of The Fall encapsulated by that quote Stella hangs on her refrigerator? Does it go back to what you were saying earlier about love being the key to overcoming trauma?

It’s not the message of the show, but it’s an important part of the message of the show. [Laughs] If that makes sense. It’s [Nurse] Sheridan’s message to Spector, but obviously it resonates with her. And it’s coming from a simpler place than Gibson would articulate. I loved the character Sheridan, and I loved the relationship between her and Spector. Again, she’s trying to save him in some kind of way. Of course she’s his ICU nurse, so she has a very important critical care kind of relationship with him, but she obviously sees something in him that she’s attempting to redeem him again and say to him, “Whatever you’ve done and whoever you are, there is the possibility of redemption.” She’s coming obviously from some kind of religious place, and therefore the religious quote is a reflection of that. That’s one of the things that religion, at its best, offers — the idea that you can be redeemed. Spector would say he can’t, and Larson says, “Well, you can’t be cured,” so there are correctives to that view.

I think the fundamental thing is true, that if you’re not loved, then you do abide in death, but that is not to say that someone like Spector, by being loved at this point in his life… The thing that really fascinates me, and the thing that haunts me, is there’s obviously arguments about whether there’s a genetic predisposition. And therefore Gibson’s very interested when she hears that Spector’s biological father is in jail for murder. She says, “A female victim?” and is told, “No, a male victim.” She’s obviously immediately thinking, “Is there some genetic predisposition?” For the most part, I think these individuals are made by appalling life circumstances, and, of course, there are people who go through similar traumas in childhood and don’t grow up to be murderers, who grow up to be good, upstanding citizens and loving fathers and things. Love in itself at the right time for Spector could have saved him perhaps, as a child.

All three seasons of The Fall are streaming on Netflix.