How Trump can fix the most persistent problem in the U.S. economy

As overall economic growth since the financial crisis has disappointed, increasing attention has been paid to low worker productivity.

And some of President Donald Trump’s key economic initiatives might be the answer to this economic drag.

On Thursday, we learned that in the first quarter productivity fell at an annualized pace of 0.6%, which was more than expected.

And given that the current unemployment rate is 4.5%, indicating that a lot of labor market “slack” has been taken up in recent years, some might argue that the prospects for increasing productivity at this point in the economic cycle are dim.

Over the last five years, U.S. labor productivity growth has averaged just 0.6%. And while the economy has added about 16 million workers over that period, slow productivity implies these workers are not increasing overall economic output. As productivity in the first quarter fell, unit labor costs rose, hitting 3% annualized in the first quarter. This indicates that employers are paying more for less.

Remembering the 1990s

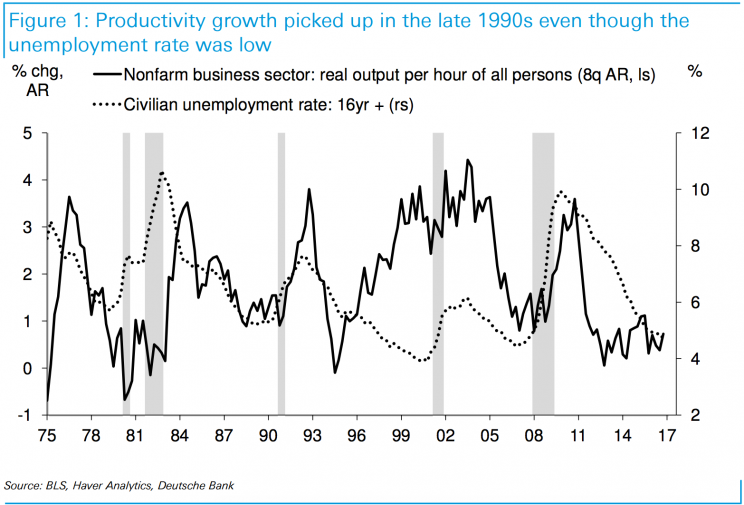

Deutsche Bank economist Joe LaVorgna, however, notes that in the late 1990s we saw a productivity boom alongside an unemployment rate that was below 5% and falling. In the late 1990s, the internet and computers were, in LaVorgna’s view, the major drivers behind the pickup in productivity.

In the current cycle, the potential for productivity gains rests in Washington, D.C., because productivity gains simply come down to boosting one thing: business spending.

“In this cycle, we believe the driving force will be a shift towards pro-business policymaking,” LaVorgna writes.

“In particular, regulatory relief and corporate tax reform, including a substantially lower corporate tax rate and full expensing of capital outlays, should boost business spending… If the economy’s capital stock expands, productivity growth will improve and thus enable a faster pace of growth relative to what has been the experience over the last several years.”

An increase in productivity and resulting benefits to overall economic growth would, of course, be welcome news to Trump, who pledged a return to 4% GDP growth during the campaign.

And while Trump has been aggressive on passing executive orders aimed at reducing regulations, tax reform requires cooperation from Congress and legislative initiatives have so far eluded the administration.

Measuring growth

Some economists, including Rick Rieder at BlackRock, have argued that there is a measurement issue in terms of how the government is accounting for the changes we all know are taking place in the economy.

“We don’t capture technology efficiently in GDP,” said Rick Rieder, the global chief investment officer of fixed income at BlackRock. “Vehicle miles traveled are at all-time record. Gasoline consumption, all-time record. Air miles traveled, all-time record. Auto sales running at 17.5 million cars [per year]. Meaning, the number we get through GDP, it’s just not calculated right. And it just lags what’s changed in the way that the economy works today.”

In other words, the slow growth and depressing productivity numbers we’re seeing reported may be underselling the overall strength of the economy.

“Real GDP growth essentially equals the sum of productivity growth and employment growth,” writes LaVorgna. “Over the past year, nonfarm payrolls have increased 1.6% while real GDP has grown 1.9%. Hence, there has been a negligible 0.3% gain in productivity.”

LaVorgna adds that, “With the unemployment rate at a relatively low level and trending lower, the pace of job growth is likely to decelerate further… consequently, for the pace of economic growth to accelerate, productivity will have to do the heavy lifting.”

For other economists, the lack of productivity is the outgrowth of a lack of innovation in the economy, an idea that falls broadly under the umbrella of “secular stagnation” and perhaps best captured in economist Robert Gordon’s book “The Rise and Fall of American Growth.”

In a note following Thursday’s productivity numbers, Chris Rupkey, an economist at MUFG Union Bank, wrote that, We don’t know if productivity is just lagging, we don’t know if the workers are just lazy…but for some reason companies don’t have enough skilled labor to pump up the volume on production and growth.

“The missing ingredient and the success for any economic expansion is always productivity.”

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland

Read more from Myles here: