Why Rising Interest Rates Won’t Benefit Savers

If there have been any victims of the Federal Reserve’s easy-money policies, they have been old-fashioned savers. People who rely on income from CDs, bank accounts and other super-safe assets have watched their cash flow dry up as interest rates have fallen to record lows.

With the Fed now signaling a pullback on some of its easy-money policies, interest rates on some types of loans are rising. Yet savers may continue to suffer because the Fed is coaxing up long-term rates while continuing to keep short-term rates extremely low. The paradox is that rising rates are punishing some consumers — such as those interested in buying a home — with no corresponding benefit to ordinary depositors. “This is not a positive development for savers,” says Greg McBride of Bankrate.com. “Banks are not going to boost yields.”

The growing disparity between short- and long-term rates arises from an apparent shift in Fed policy meant to curtail some, but not all, of the monetary stimulus measures that have helped recharge the economy for the past five years. The Fed and its chairman, Ben Bernanke, have signaled recently that the central bank may begin to rein in “quantitative easing,” or QE, by the end of the year if the economy continues to grow at its expected pace. This is the program in which the Fed buys huge amounts of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, helping to push down the interest rates borrowers pay.

Quantitative easing has basically worked as intended. When the Fed was fully committed to such bond purchases, interest rates on the closely linked 10-year Treasury note and 30-year mortgage fell to record lows. That was an obvious boon for the U.S. government, which saw its borrowing costs plunge even as it racked up more and more debt, and also for home buyers who have enjoyed the best housing affordability on record.

A sharp rise

But since the Fed indicated it might cut back on QE, rates on both types of loans have shot up, because investors anticipate that reduced demand for those assets in the future will force borrowers to pay more. Rates fluctuate all the time, but long-term rates have spiked by a full percentage point during the past two months, an unusually sharp rise that has spooked investors and contributed to the big selloff in stocks.

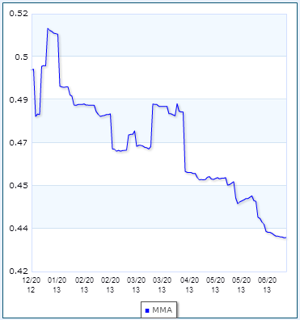

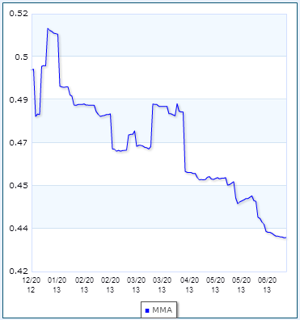

That quick rise in rates, however, has not touched shorter-term assets such as bank accounts or CDs. The following two charts from Bankrate, in fact, show a widening gap between long-term loans such as 30-year mortgage rates (first chart), and liquid holdings with no long-term commitment, such as money market funds (second chart):

Average rate on a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage:

Average rate on a money-market fund:

The only rates that have risen appreciably during the past two months, in fact, are those on loans with a duration of 10 years or more. The average rate on a 30-year mortgage, for instance, has jumped from about 3.4% at the beginning of May to nearly 4.4% today, according to Bankrate. Yet the average rate on a 5-year jumbo CD, at 1.3%, is just a hair higher than it was at the beginning of May and actually lower than it was in mid April. Rates on auto loans and credit cards — also linked closely with short-term rates — have been flat as well.

While allowing longer-term rates to rise, the Fed has made clear it plans to keep short-term rates as low as possible until 2015 or perhaps even 2016. It will do that by keeping its own “federal funds” rate — the rate it charges commercial banks for short-term loans — at or near zero, which allows banks, in turn, to lend out money at slightly higher (but still extremely low) rates and still make a profit.

Pushing short-term rates down is conventional monetary policy, which is supposed to benefit the economy by making credit cheap for companies and encouraging investment. The Fed began lowering short-term rates in 2007, then introduced QE in 2008, when short-term rates hit zero, maxing out that approach. So as the Fed gradually withdraws unprecedented amounts of monetary stimulus, it makes sense that it would curtail the controversial quantitative easing program first, while leaving the traditional easing program in place longer.

The market itself is helping keep interest rates on bank deposits low as well. Deposits at banks have grown by more than lending during the past several years, which means banks have more deposits on hand than they need to meet demand for loans. With lending still at depressed levels, banks have no incentive to pay higher rates on the deposits they hold, since they can’t make up the difference by lending out the money at higher rates. “Banks have plenty of deposits they can’t lend out as it is,” says McBride.

Nowhere to hide

For savers, there’s really nowhere to hide. Rising rates on Treasury bonds make those a slightly better investment, yet most people buy Treasuries through bond mutual funds, which stand to lose money as rates go higher. Investors who buy bonds directly will benefit from the rise in interest payments, but only if they hold the bond for the duration of the note. It’s also possible rates could drift back down as investors get more comfortable with the prospect of a Fed pullback, which would make bonds paying current rates a good investment. But that would require the kind of risk-taking conservative savers usually prefer to avoid.

Part of the Fed’s overall strategy has been to push interest rates so low that traditional, risk-averse savers move their money out of “safe” assets into riskier, higher-returning investments such as stocks. That seems to be one part of the strategy that hasn’t really changed. Die-hard savers can complain all they want about Bernanke & Co., but fighting the Fed still doesn't look like a smart financial move.

Rick Newman’s latest book is Rebounders: How Winners Pivot From Setback To Success. Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman.