2 Top Food Stocks to Buy Now

The food chain around the globe is vast. It's easy for us to single out the obvious players: the farms that grow the food, the grocery stores that sell it, and the restaurants that serve it.

But the network is so much bigger. It includes chemical companies that make fertilizers, manufacturers that make machines used on farms, middlemen who take farms' raw materials and turn them into packaged goods, and distributors who move them all over the world.

Image source: Getty Images.

There are tens of thousands of companies involved in the food chain. And yet, I believe only two such companies have stocks worth buying now -- and neither are pure-play grocery stores, restaurants, or food processors.

Those two stocks are:

Company | Connection to Food |

|---|---|

Amazon.com (NASDAQ: AMZN) | Parent of Whole Foods Market with growing grocery-delivery ambitions |

Walmart (NYSE: WMT) | Mega-retailer that relies on groceries for over half of U.S. sales |

The importance of moats in investing

But before we get to those companies, it's important to note why there are so many food companies left off this list. It all comes down to a company's moat -- or sustainable competitive advantage. Companies with moats can not only grow, but also fend off competition for decades; that allows earnings to compound, creating huge wins for investors.

In general, there are four types of moats a company can have:

Network effects: A company's offering gains utility with each additional user or customer. A prime example is Facebook -- there's no reason to join a social network if others aren't on it. Each additional user makes Facebook more valuable.

High switching costs: Deciding to switch away from a company's services would be a pain in terms of time, resources, and money lost. A prime example would be leaving your bank. So many automated payments are tied to your accounts that it would be a logistical nightmare to switch banks.

Low-cost provider: If a company can offer something at a lower cost than the competition, it will always win business. This is the basis for Amazon's delivery success. With a bigger network of fulfillment centers than anyone else, it can afford free one-day delivery on more items (with a Prime Membership) than anyone else.

Intangible assets: This includes things like brand value, patents, and government regulation. Prime examples of companies that benefit from these moats are Apple (which has the most valuable brand in the world), drug companies (whose patents allow them to charge high prices), and utility companies (which are heavily regulated).

Why restaurants and food stores aren't good food investments

The big problem with most restaurants is that they have, at best, very weak moats. Already, grocery businesses are feeling the pinch; the past decade has seen a huge number of operations either consolidated or taken private. Consider the factors at play:

There are no network effects involved with restaurants or grocery stores. In fact, it could be argued that once customers reach a critical mass, it becomes a pain to frequent such locations.

Some stores gain a measure of high switching costs with customer loyalty programs, Starbucks' rewards program being a great exemplar. But largely, there's no real switching cost involved with going to the competition.

Companies with enormous scale can sometimes lock in their food for lower prices, but this advantage is being quickly eroded by demographic changes we'll discuss below.

Brand value -- once the most important thing food stores had -- has disappeared.

The biggest trend to be aware of is that the combination of e-commerce, new technologies, and the generational shift in preferences that millennials have ushered in are changing the face of food.

As former hedge fund manager Mike Alkin outlined in a January 2018 conference, millennials are after three things in their food and packaged goods:

Products that come from local organizations.

Products that come from small organizations.

Products that are, when possible, organic.

Publicly traded companies by their very nature cannot fulfill these first two requirements. Crucially, Alkin has found that when a smaller brand is bought out by a bigger conglomerate, millennials will often pivot to a new product as a result, making the acquisition virtually worthless over the long run.

Already, the biggest names in food are struggling to bring in more foot traffic. Huge companies like McDonald's and Starbucks have only been able to increase comparable-store sales because of rising prices -- not because they're attracting more customers.

Does that mean that there will be no winners in the restaurant business? Absolutely not. There will be another Chipotle that comes along and -- for reasons that are almost impossible to predict -- strikes a chord with customers. When that happens, investors will likely enjoy a huge windfall.

But forecasting with any level of certainty which companies those will be is very difficult. Chipotle itself has actually figured that out the hard way: Its attempts at pizza, Asian, and hamburger joints have all been met with a rousing "meh" from consumers.

As such, I think there are better places for your money in the food sector.

Why aren't there any distributors on the list?

"Fine," you might say, "I can see why you left restaurants and grocery stores off the list. But why distributors?"

Such an argument has merit. It costs tens of millions of dollars to build out distribution networks. They aren't easy to build out -- tons of red tape involving safe transport and refrigeration of goods are at play. And we are hugely reliant upon these distributors to get our food from farms and factories to our kitchen tables.

The industry's three biggest players -- Sysco (NYSE: SYY), US Foods (NYSE: USFD) and United Natural Foods (NYSE: UNFI) -- all have formidable moats around them: low production costs and moderate switching costs. Because these companies have built out their distribution networks, they can send food across the country for lower internal costs than upstarts. And because they become ingrained in the operations of food producers, there's a strong incentive to stay with the distributor you're familiar with. No one wants to unnecessarily mess with a distribution network that is working just fine.

But there's an 800-pound gorilla moving into the distribution industry that could upend everything: Amazon. We'll get into the specifics of why below. Let's just say for now that Amazon already has the distribution network to challenge Sysco and its peers. And because it gets lots of cash from other sources -- like Amazon Web Services -- it can offer prices low enough to lure customers away.

What about the fast-growing food delivery niche?

This article was originally titled "3 Top Food Stocks to Buy Today." First-mover GrubHub (NYSE: GRUB) was also going to be on the list, and for good reason. The food delivery niche is growing like gangbusters: Ark Invest believes it could reach anywhere from $80 billion to $3 trillion by 2030. And GrubHub is a market leader.

The company also benefits from (what should be) a very wide moat. The number of restaurants signed up with GrubHub almost quadrupled from 2014 to 2019, with a healthy boost provided by acquisitions. Many of those restaurants could eventually get locked-in via high switching costs through one of GrubHub's most recent acquisitions, LevelUp, a platform that allows restaurants to manage payments, orders, and loyalty programs. Once the data is on that platform, the costs associated with leaving -- and losing that data -- become high.

At the same time, there are powerful network effects at play: As more people use GrubHub (there are over 19 million), restaurants have incentive to list on the site. As more restaurants list, it draws in ever more diners. In theory, that's a virtuous cycle that's tough to stop.

But certain industry dynamics would give any investor pause. None was more eye-opening than looking at how the network effects aren't global -- in fact, they usually end at a major city's limits. For instance, what good does it do a Dallas resident to know that lots of New York City burger joints are on GrubHub?

That helps explain why, according to research by SecondMeasure, food delivery is highly fragmented by region. GrubHub has the most market share in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston, for instance. But in Dallas, Houston, Washington, Phoenix, and San Francisco, DoorDash is the market leader. In Miami and Atlanta, Uber Eats is the leader.

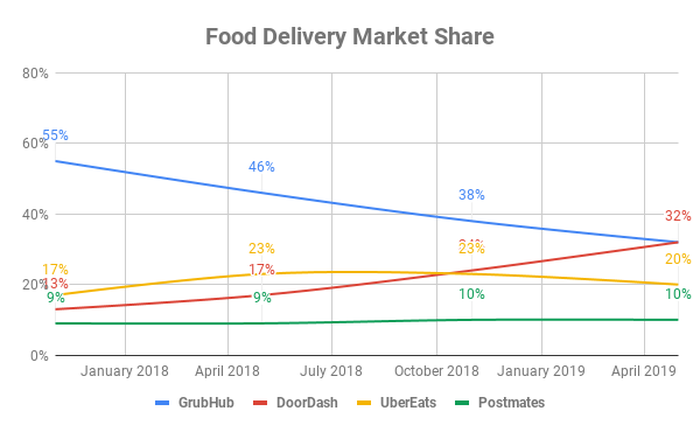

Most concerning, while the overall market has continued to grow, GrubHub's market share plunged in less than two years leading up to the summer of 2019.

Data source: Second Measure via ReCode. Percentages rounded to nearest whole number.

This will continue to evolve. By the time you read this, GrubHub may have already regained its footing. But the dynamics are more important than the specifics: What has happened before (drastic loss of market share) can easily happen again.

One of the biggest explanations for this is that diners don't seem to be all that loyal to any one program. Many of GrubHub's regular users, for instance, are also users of Uber Eats and DoorDash. In the end, that starts a pricing war: Each company wants to give customers the best possible deal.

While that's awesome when you and I want to order a cheap burrito, its awful for investors. Things may eventually stabilize in the industry, but I think it's worth waiting on the sidelines until that moment comes.

Why Amazon has a leg up in the food wars

Which brings us to Amazon. Of all the companies that have even the slightest interest in the food industry, Amazon is far and away the strongest. Let's start with the most important aspect to evaluate: Amazon's (multiple) moats.

Intangible assets: While brands come and go, it's worth noting that Amazon has one of the strongest in the world.

High switching costs: It would be very difficult to find a deal that even comes close to the advantages of being an Amazon Prime member. Not only is there free two-day shipping, but there's also access to a wide range of streaming content, special online deals, and in-store savings at Whole Foods. There are also high switching costs associated with using Amazon Web Services, as clients know that migrating to a different server can be expensive and logistically challenging.

Network effects: Amazon admitted in 2019 that third-party sellers had become the dominant vendors on Amazon.com -- not the company itself. That means they're choosing to list their goods on the platform and have Amazon fulfill those orders. It's not hard to see why: It's long been one of the most-visited sites in the world. As more customers visit, merchants are incentivized to list -- which only draws in more customers.

Low-cost production: But for what we're talking about, the real moat comes from low-cost production. Because Amazon has hundreds of fulfillment centers worldwide, it can guarantee fast delivery for a lower internal cost than anyone else. And matching that scale is prohibitively expensive.

As for food, the real coup came in 2017 with Amazon's $13.7 billion acquisition of Whole Foods. Few commentators describe Amazon's thinking better than Ben Thompson, who runs the subscription blog Stratechery.

In Thompson's thinking, we sometimes get distracted by the fact that Amazon has become "The Everything Store" -- an online destination where you can buy anything. Instead of focusing on the store, he argues, we should focus on all the tools Amazon could afford and justify building to serve The Everything Store:

Amazon could build Amazon Web Services because even if it failed in its infancy, it would still serve the company well. It has since become Amazon's main profit engine.

It isn't hard to justify building out those fulfillment centers, given the volume of what Amazon sells. What other company could justify such ambitions to investors?

When it comes to shipping and delivery, Amazon has had little trouble building out a network that could soon challenge FedEx and UPS.

Which brings us to Whole Foods. Thompson argues that Amazon wasn't really buying a business so much as buying a customer. If Amazon has a customer -- Whole Foods -- that needs shipping services specific to food, it can justify the investments in making it happen. Those investments will not only help Whole Foods, but anyone else who wants Amazon to ship their food.

And because Amazon has lots of other profit levers -- like Amazon Web Services, Fulfillment by Amazon, and advertising -- it can offer those food distribution deals for less than the competition. In essence, delivery can be subsidized, at least until Amazon has captured enough of the market where it can start flexing its pricing muscles.

That, in a nutshell, is why I left Sysco, US Foods, and their peers off this list: Amazon alone can afford such a distributed delivery network. And the combination of moats tips the scale in the company's favor within the food market.

Why Walmart is able to challenge Amazon

Had I written this article in 2017, Amazon may very well have been the only company I included in this list. But retail giant Walmart has shown an impressive knack for turning its brick-and-mortar locations -- once a key competitive asset that became a liability in the age of e-commerce -- back into an asset.

In 2016, the company made a huge splash by spending $3.3 billion to acquire e-commerce specialist Jet.com. By 2019, the company's U.S. e-commerce operations had begun to boom.

Data source: SEC filings.

The key behind this move is Walmart's ability to leverage its existing locations. Customers can place an order online (including groceries, which accounted for 55% of U.S. Walmart sales in 2018) and pick it up at their nearest Walmart. With over 11,000 locations worldwide, that's a valuable -- and convenient -- proposition.

As my fellow Motley Fool Rich Duprey argued, if it really wants to dominate a niche in e-commerce, focusing on groceries would be Walmart's best bet. Its physical locations aren't just shopping places for you and me, but also "pick centers" where merchandise can be selected and packaged. The company is going to great lengths to leverage this strength, as Duprey noted:

[As of mid-2019] the retailer has 3,100 stores that offer grocery pickup, including innovations like towers where customers can collect their online grocery orders. More than half of the stores will offer same-day delivery by the end of the year. Walmart is also trying a new delivery service that puts customers' fresh food orders into their refrigerators. And it is investing in automated order fulfillment and driverless delivery technology.

Leveraging these assets gives it superiority in groceries versus Amazon, which will likely have to partner with other retailers if it hopes to have anywhere near the same physical footprint as Walmart.

I'm not betting against Amazon, either. But I think Walmart's stock offers a favorable valuation. While many e-commerce companies have yet to turn a meaningful profit or free cash flow (except Amazon), Walmart routinely spits out over $15 billion in free cash flow. While the stock fluctuates every day, it rarely trades for the type of nosebleed valuations found at Amazon.

The larger point is that Walmart is attractively priced, offers a sustainable dividend, and is turning its retail centers back into a moat that can protect its business.

A final word about food stocks

Over the next five years, I have little doubt that many food-related stocks will outperform Amazon and Walmart. Why haven't I included them in this list? Because I simply can't predict which stocks they will be.

If we can truly use both hands to grab the idea that the future is unknown, then we'll embrace just how important analyzing moats really is. Companies that have them offer outsize returns with less risk. Companies without them could boom...or fall flat on their face -- and we shouldn't fool ourselves into thinking we can tell one from the other.

Because Amazon and Walmart both have sizable moats surrounding their businesses, I think they're the best bets within the food industry to beat the broader market over the next decade.

John Mackey, CEO of Whole Foods Market, an Amazon subsidiary, is a member of The Motley Fool's board of directors. Randi Zuckerberg, a former director of market development and spokeswoman for Facebook and sister to its CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, is a member of The Motley Fool's board of directors. Brian Stoffel owns shares of Amazon and Facebook. The Motley Fool owns shares of and recommends Amazon, Chipotle Mexican Grill, Facebook, FedEx, and Starbucks. The Motley Fool recommends Grubhub and Uber Technologies. The Motley Fool has a disclosure policy.

This article was originally published on Fool.com