5 million Native Americans getting some respect from Dem candidates

Presidential elections are decided by many things: media exposure, financial backing, personal chemistry, timing and luck. Policy positions often are just a way of signaling where a candidate stands on the political spectrum. But 2020 is shaping up to be different, the most ideas-driven election in recent American history. On the Democratic side, a robust debate about inequality has given rise to ambitious proposals to redress the imbalance in Americans’ economic situations. Candidates are churning out positions on banking regulation, antitrust law and the future effects of artificial intelligence. The Green New Deal is spurring debate on the crucial issue of climate change, which could also play a role in a possible Republican challenge to Donald Trump.

Yahoo News will be examining these and other policy questions in “The Ideas Election” — a series of articles on how candidates are defining and addressing the most important issues facing the United States as it prepares to enter a new decade.

About 5 million Native Americans live in the United States. The 573 federally recognized tribes across the country have long suffered from high poverty rates, lagging infrastructure, poor education and endemic violence against women.

Presidential campaigns usually ignore Native Americans and their unique position and struggles. The 2020 race might be different. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, two of the campaign’s biggest names, will attend the first-ever presidential forum devoted to the issues on Aug. 19 and 20.

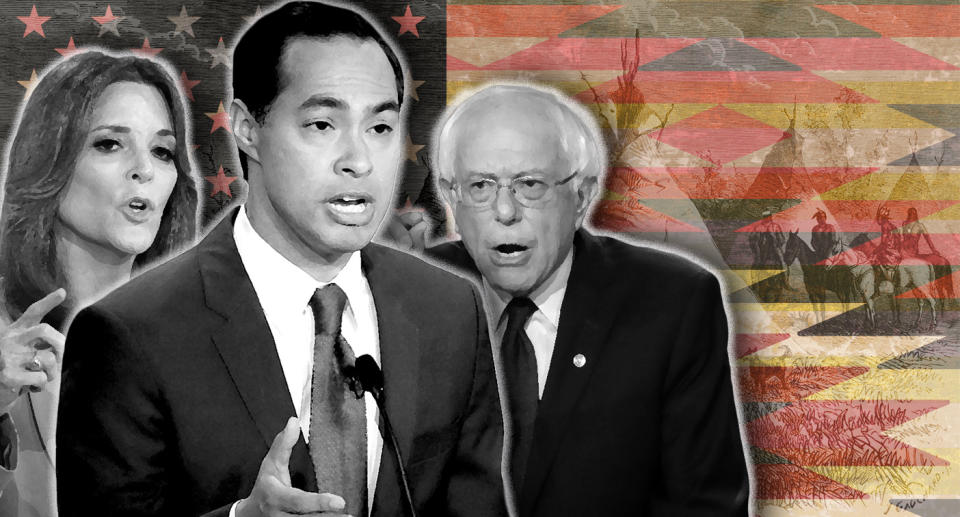

Four Directions, a Native American voting rights group, is sponsoring the forum, which will be in Sioux City, Iowa. The other Democratic candidates who plan to attend are Julián Castro, Amy Klobuchar, John Delaney, Marianne Williamson and Steve Bullock.

Warren’s presence will likely be controversial because of her previous claims of partial Native American ancestry. She was widely criticized for releasing a DNA test in October 2018 that showed Native American heritage going back several generations. Shortly after announcing her presidential campaign in February, Warren apologized for claiming descent from the Cherokee tribe based on family anecdotes.

Frontrunner Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, another top-tier candidate, haven’t announced whether they will attend the forum. Only Sanders, Castro and Williamson have released proposals that specifically address Native American issues. O.J. Semans, executive director of Four Directions, said candidates will discuss the sovereignty of tribal nations, the protection of Native American lands and health care, among other issues.

Four Directions has sued South Dakota, Montana, Nevada and Arizona to fight for better access to voting on tribal reservations. Hours before the Democratic debate on July 31, Semans told Yahoo News that he could guarantee candidates wouldn’t mention the issues of the “First Americans.” He was right.

Health care has been a leading issue in the Democratic primary. What many candidates don’t realize, Semans said, is that Native Americans are already promised health care from the federal government.

The federal government launched the Indian Health Service in 1955 to provide direct medical services to members of federally recognized tribes. The IHS was created “to ensure the highest possible health status for Indians and urban Indians and to provide all resources necessary to effect that policy.”

IHS provides health care to 2.5 million Native Americans living on or near reservations. The health of Native Americans often lags far behind “the highest possible health status.” The life expectancy of Native Americans is 5.5 years lower than the country’s average, according to IHS data, and Native Americans are more likely than the average American to die of cancer, heart disease, flu, pneumonia, drug overdoses and suicide.

On the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota, where Semans lives, the IHS emergency room was forced to close in 2015 because of dangerous conditions. It was fixed and reopened, but the local newspaper says the improvements weren’t permanent.

“All of the things they’re talking about out there are the same things we’re dealing with here,” Semans said. “But we’re dealing with it because of the treaties the government hasn’t honored from the day they signed them.”

The U.S. government signed 370 treaties with tribal nations between 1781 and 1871. These treaties usually involved exchanging tribal lands for other “reserved” territory and various benefits and protections. Tribes that resisted the expansion of settlements were met with military force.

In Seminole Nation v. United States (1942), the Supreme Court interpreted the relationship between Native American tribes and the federal government to involve “moral obligations of the highest responsibility and trust.” The federal government now provides services beyond treaty requirements, according to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

But Semans sees the IHS as an example of the federal government not fulfilling its obligations. Congress allocated $5.8 billion for the IHS in fiscal year 2019, or $2,109 per capita. In comparison, the federal prison system spent $8,602 per inmate on health care in fiscal year 2016.

Native Americans would be able to maintain their coverage from the IHS under Sanders’s Medicare for All plan. At the forum in August, Four Directions hopes to push candidates from the comfort zone of a “one-size-fits-all approach,” Semans said. Candidates will be asked if they will make improving health care for Native Americans a priority, and about tribal sovereignty and the protection of Native American lands.

All Native American reservations are federal lands, meaning that only federal laws apply there. Contrary to popular belief, Native Americans do pay federal income taxes (e.g., on wages from outside jobs) except on income earned from the reservation land itself. States usually have no jurisdiction on reservations. Some, however, have tried to pass laws taxing non-natives on reservations and claim greater jurisdiction over arrests on trust lands.

“The federal government is supposed to step in on our behalf and protect, which most of the time they do not do,” Semans said. “It’s almost being the stepchild.”

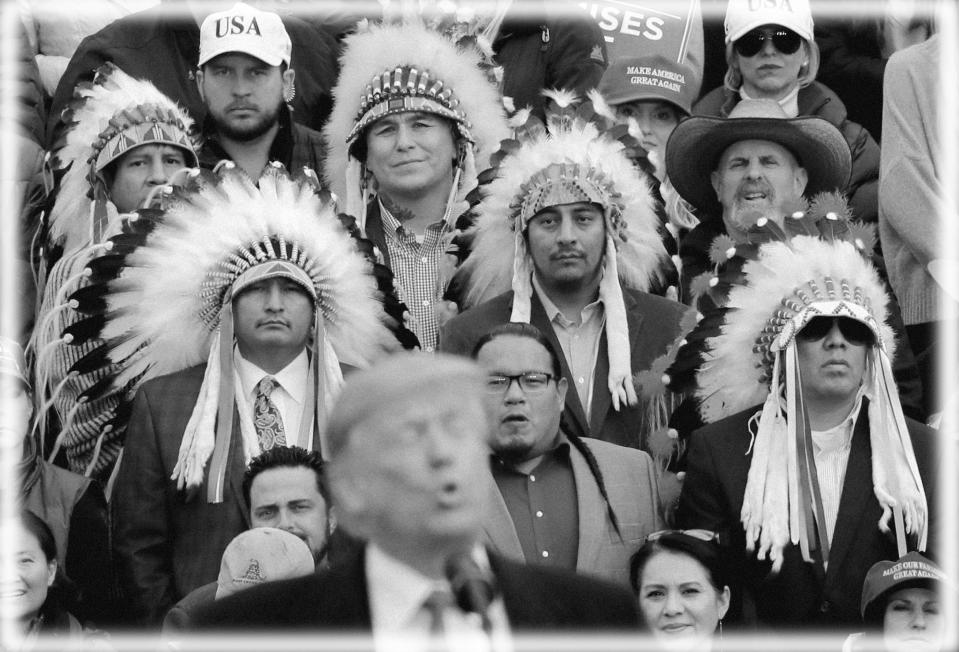

The Trump administration has moved from traditional indifference to tribal sovereignty toward a more combative relationship. In 2018, tribes requested exemptions from the Department of Health and Human Services for Medicaid work requirements being considered in several states. Work requirements would be difficult to meet on tribal reservations, where unemployment runs well above the national average. There are precedents for exempting Native Americans from mandates that are inapplicable or difficult to meet on reservations, such as the Affordable Care Act’s mandated individual health care coverage.

Not only did the administration break with these precedents by refusing the request, it went against centuries of precedent by arguing that tribes were a race, not sovereign nations that enjoyed treaty status with the United States.

The leasing of federal lands to oil companies in recent years is another contentious issue. During the Obama administration, Native American tribes resisted planned construction of the Keystone XL pipeline and Dakota Access Pipeline, citing concerns about potential damage to ancestral lands and the environment. Developers planned to build the Dakota Access Pipeline under Lake Oahe near the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in North Dakota.

Obama rejected the Keystone XL proposal in 2015. Only four days after taking office in 2017, President Trump signed proclamations moving both pipeline projects forward.

Julián Castro, the former Housing and Urban Development secretary, has released the most comprehensive plan to help Native American communities. Castro’s plan, titled People First Indigenous Communities, addresses issues including tribal sovereignty, health care, housing and education.

“The federal government has repeatedly failed to honor treaty obligations, respect unique government-to-government relationships, and allowed corporations to exploit sacred land for their own profits,” Castro wrote in a July 25 post on Medium.

Castro pledges that, if elected, his administration would honor tribal sovereignty and prior treaty commitments. His plan would establish a White House Council on Indigenous Communities, bring back an annual tribal nations conference and create advisory committees in every Cabinet-level federal agency.

Castro also calls for greater funding for federal programs that assist indigenous communities — $2.5 billion for housing grants, $150 billion for public schools and $150 million for business development. Other proposals focus on “cultural sovereignty” by investing in the return of cultural property to tribes.

Sanders and Williamson, the author and self-help guru, are the only other candidates who have policies that specifically aim to help indigenous communities. Their proposals focus on tribal sovereignty and pledge additional aid, but mostly lack specific details about how they hope to reach those goals.

Warren released plans on Wednesday to assist rural Americans and the farm economy. While her plans aren’t specifically focused on Native Americans, she is calling for $5 billion in federal grants to expand access to internet on reservations, and additional funding to help tribal governments acquire and consolidate reservation lands.

Both Sanders and Castro have proposed ways to address domestic and sexual violence against indigenous women. More than 4 in 5 indigenous women have experienced violence, according to the Indian Law Resource Center, and more than half have faced sexual violence. The plans from Sanders and Castro urge Congress to reauthorize the Violence Against Women Act with an expansion of tribal jurisdiction to prosecute non-native criminals.

Castro’s plan goes one step further by proposing a presidential task force to tackle the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls and human trafficking on indigenous lands.

Castro proposes the federal government should stop leasing lands for the exploration and extraction of fossil fuels if those lands hold cultural significance to indigenous communities. He would require federal agencies to obtain the consent of Native American communities to begin major infrastructure projects.

While Sanders’s plan doesn’t mention the leasing of federal land, he joined a protest against the Dakota Access Pipeline outside the White House in September 2016. Williamson has proposed giving federal lands in the Black Hills of South Dakota back to the Sioux Nation.

Congress creates the federal laws that govern reservations, but the president can set the tone for how their administration will interact with Native American tribes. It took Trump only four days in office to sign an executive order affecting the leasing of federal lands. A Democratic president could quickly reverse those policies.

Native American voter turnout has historically lagged behind the national average for decades. High poverty rates, low high school graduation rates and long distances to polling places all depress turnout. Voter ID laws in several states require proof of address that may be impossible to obtain on a reservation, where houses may not be numbered.

One such law was passed in North Dakota ahead of a hotly contested midterm election in 2018. Semans accused the Republican-controlled legislature of seeking to suppress Native American voting. Four Directions worked with tribal leaders to determine addresses and print voter IDs in time for the election. The end result was record-high turnout among Native Americans.

The 2018 midterms were historic for another reason: Sharice Davids of Kansas and Deb Haaland of New Mexico became the first Native American women elected to Congress. Haaland has defended Warren amid outrage over her DNA test. Last week, she endorsed Warren’s presidential bid, calling the senator a “great partner for Indian Country.”

About 70,000 people decided the 2016 presidential election in three states that gave Trump a victory in the Electoral College. Semans makes the case that, as Native American turnout increases, the 2020 candidates shouldn’t forget about millions of potential voters.

“Natives are now realizing their political power, and if they’re ignored, they’re going to ignore the candidates,” Semans said.

Download the Yahoo News app to customize your experience.

Read more from Yahoo News:

FBI document warns conspiracy theories are a new domestic terrorism threat

Marianne Williamson on reparations and her emails with Oprah

'It's blasted across America': How Fox and Sean Hannity amplified a Russia-fueled conspiracy

Democrats resume search for a 'smoking gun' to bring down Trump

PHOTOS: President faces protests on visit to cities hit by mass shootings