'This is life or death': Workers at Amazon, Target, Instacart hold nationwide strike on International Workers Day

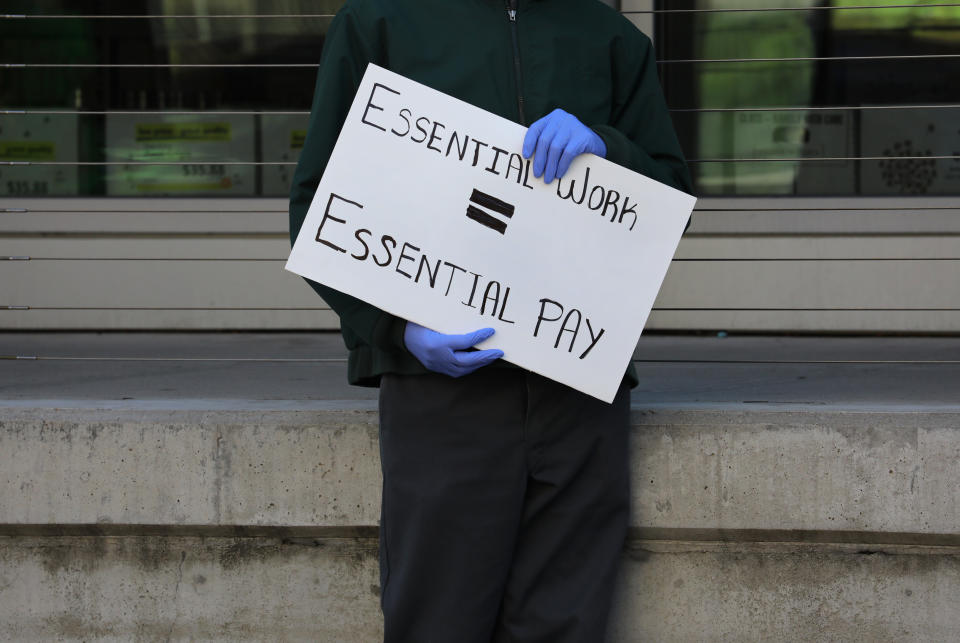

Essential workers nationwide at Amazon (AMZN), Whole Foods, Target (TGT), Instacart, and other companies held a coordinated strike on Friday that marked International Workers Day, saying they fear for their lives due to potential coronavirus exposure and calling for workplace safety protections, paid sick leave, and hazard pay to ensure their well-being amid the pandemic.

The action on Friday is the latest and broadest demonstration in a string of strikes since the coronavirus outbreak forced hundreds of millions of Americans into their homes last month, spiking demand for e-commerce and delivery as Amazon and other companies posted strong sales in recent earnings reports. Workers have expressed frustration over what they consider inadequate safety measures and compensation amid the heightened risk.

The strike on Friday marked the first coordinated workplace action by workers from several of the companies at once. The protests remained predominantly virtual, as participating workers posted messages on social media; but a small demonstration was held outside of an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island.

“This is life or death — that’s what we all have in common here,” says Chris Smalls, a former Amazon warehouse worker whom the company fired on the same day he participated in a strike on March 30. (The company says it did not retaliate against Smalls but rather terminated him for violating social distancing rules after several warnings).

“We put aside that our companies are competitors,” adds Smalls, who said he helped organize the strike over conference calls with workers that began two weeks ago. “We all realize that the time is now for us to speak up — that’s why the alliance was easy to form.”

Willy Solis, a gig worker who has delivered for Target subsidiary Shipt since last November, said he fears coronavirus exposure because he’s immunocompromised but lacks the equipment necessary to protect himself.

“They haven’t provided us with anything,” says Solis, who adds that he used to make as much as about $690 per week with the company but has significantly reduced his work. “I myself am still waiting for masks — ordered some but they haven’t come yet.”

(“Shipt provides face masks and gloves for shoppers to pick up from their local Target store each day,” a Shipt spokesperson said, adding that the company has sent protective equipment to active workers or those in high-risk areas.)

Worker demonstrations at Shipt began last month, but Solis helped plan the coalition action on Friday because it strengthens the demands of all workers involved, he said.

“The reality is that the companies continue to ignore us individually,” he says. “As a collective whole, we’re showing unity and solidarity together.”

Instacart, a digital grocery delivery company that relies on independent contractors it refers to as “shoppers,” said it has prioritized worker safety amid the pandemic, and will continue to do so.

“We remain singularly focused on the health and safety of the Instacart community,” Instacart spokesperson Charlotte Healow says. “Our team has been diligently working to offer new policies, guidelines, product features, resources, increased bonuses, and personal protective equipment to ensure the health and safety of shoppers during this critical time.”

Target noted low turnout among striking workers, and highlighted measures implemented since the outbreak such as a $2 per hour pay increase as well as masks and gloves made available to workers.

“We’re aware of less than 10 team members who chose to participate in today’s activities,” Target Spokesperson Shane Klitzman said. “The vast majority of our more than 340,000 frontline team members have expressed pride in the role they are playing in providing an essential service in our stores across the country, and we applaud them for their efforts.”

Whole Foods said criticism of the company doesn’t represent the overall sentiment of its workforce, and noted its own pay increase of $2 per hour as well as safety measures like mandatory temperature screenings and plexiglass barriers at checkouts.

“We continue to operate our stores and serve our customers without interruption,” a Whole Foods Spokesperson says. “Statements made by this small group of individuals, some of whom are not employed by Whole Foods Market, misrepresent the full extent of our actions in response to this crisis and do not represent the collective voice of our more than 95,000 Team Members.

Meanwhile, Amazon strongly rebutted the claims of unfair employee treatment and said the demonstration on Friday has not interrupted operations.

“The fact is that today the overwhelming majority of our more than 840,000 employees around the world are at work as usual continuing to support getting people in their communities the items they need during these challenging times,” Amazon Spokesperson Rachael Lighty says. “While there is tremendous media coverage of today’s protests we see no measurable impact on operations.”

Less than five protests took place nationwide on Friday, Amazon said, involving less than 100 people, most of whom were not Amazon employees.

The company has implemented safety measures that include efforts to take the temperature of workers before they enter U.S. facilities, provide all workers with protective masks, and give partial pay to workers who are sent home with a fever.

Jane McAlevey, a longtime union organizer and author, acknowledged that the strike on Friday only involved a fraction of workers at the companies but said the actions are significant nonetheless.

“They’re still small but the number of people participating is growing,” McAlevey says. “Importantly, the public’s awareness of them is growing because of the COVID crisis. Many Americans see what these workers are going through.”

“I think we have a ways to go with employers like Amazon and Whole Foods,” she says. “They’ve got billions and billions. They’ll fight tooth and nail.”

Worker demonstrations at the major brands began on March 30, when Instacart workers nationwide refused to fulfill orders and Amazon warehouse workers at a facility in Staten Island walked off the job. The next day, workers at Whole Foods held a sickout, demanding protective equipment and other safety measures. Late last month, on April 21, Amazon warehouse workers staged their largest refusal to work.

Labor outlet Payday Report has identified more than 150 wildcat strikes — workplace demonstrations undertaken without union approval — since March, when it became known that the coronavirus had spread widely in the U.S.

On Thursday, Amazon reported revenue of $75.5 billion, a leap of 26% over the same three-month period last year that’s likely attributable to the reliance on e-commerce as many Americans have stayed in their homes. Amazon announced in March that it would hire 100,000 workers to meet the increased demand, and in April said it would add 75,000 more.

“All of those companies and industries are frantically trying to get more workers,” says Ileen DeVault, a professor of labor history and the director of The Worker Institute at Cornell University. “And I think that’s exactly why the workers have realized they can’t just sit back and take the treatment they’ve received in the past.”

“While some people are sheltering in place there are a lot of ordinary workers having to go out and work often in dangerous conditions,” she adds.

Jordan Flowers, 21, a warehouse worker at the Staten Island facility, has not gone in for a shift since Feb. 28 out of fear of contracting the virus, he said. But he has helped organize warehouse workers, including the strike on Friday.

At the end of April, Amazon stopped allowing workers to take unlimited unpaid leave, leaving Flowers concerned that he’ll soon lose his job, he said.

“Too many people with families, too many with children are getting infected,” he says. “I don’t want to be in that boat because of my job.”

Addressing his comments to Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, Flowers vowed to continue the demonstrations.

“We’re going to continue until he does something about it,” Flowers says. “We’ll be back every week.”

Correction: In the original version of this story, Shipt employee Willy Solis said he had made as much as $800 per week with the company. After publication, he corrected the figure, telling Yahoo Finance that the most he had made in a week was $694.

This story has been updated with statements from Target, Shipt, Whole Foods, and Amazon.

Read more:

'We're risking our lives': Why Amazon warehouse workers are walking out over coronavirus fears

Top unions call for closure of all Amazon warehouses — experts say it would be disastrous

Workers condemn coronavirus relief bill's loophole for big companies

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance