Where are America's truck drivers?

There is a truck driver shortage in the U.S. At least according to multiple media reports, the American Trucking Association, and the cost of shipping goods on trucks.

In June, the ATA’s chief economist Bob Costello said that, “Finding enough qualified drivers remains a tremendous challenge for the trucking industry and one that if not solved will threaten the entire supply chain.”

Jobs data released Friday, however, doesn’t tell quite the same story of an industry in crisis.

Employment in the sector only just topped the pace of overall job growth in the economy last month — employment in the trucking business rose 1.7% over last year in June while the overall economy saw a 1.6% increase in workers.

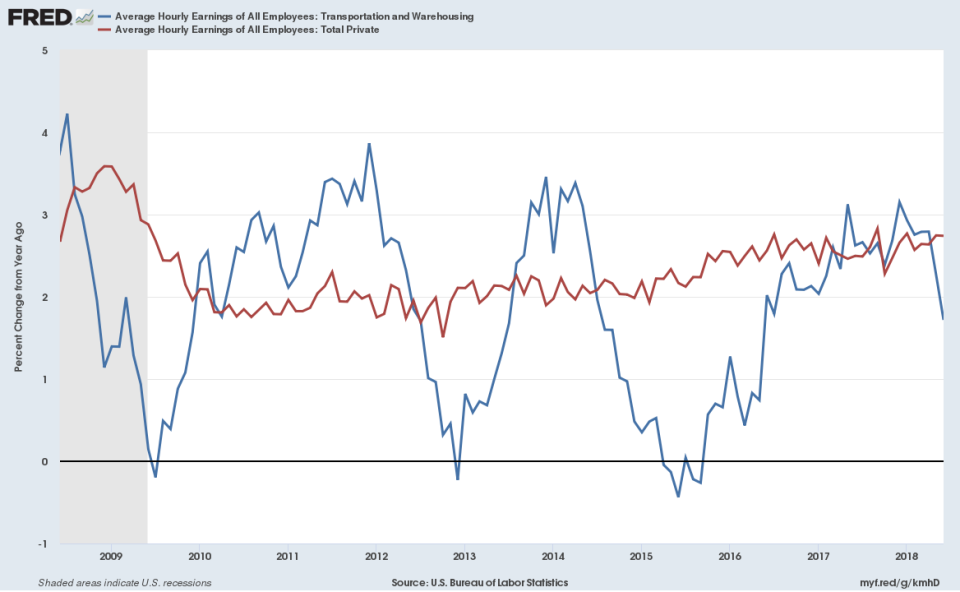

Meanwhile, wage increases in the transportation and warehousing industry have risen less than the rest of the private sector in the last two months. And though this broader sector-level read on wages doesn’t isolate truck drivers the way employment data do, one would still expect to see the industry outperforming the rest of the labor market.

In a note to clients following Friday’s jobs report, Michael Feroli, an economist at JP Morgan, wrote that as wage growth disappointed expectations in June, “the contrast with common anecdotes about pay growth is striking, particularly when one digs down and sees wages in industries like long-haul freight trucking up only 1.4% over a year ago.”

In recent months, we’ve highlighted how economic data that hinges on qualitative evaluations of the economy like the Fed’s Beige Book and the NFIB’s small business optimism index have indicated that labor is scarce and wages are likely to go up. And the economic textbook teaches that when the supply of something — in this case, labor — declines while demand for that good or service increases, the price must go up.

The actual data, then, are either lagging this anecdotal assessment of the economy or the anecdotes are biased in favor of employers who always want the same thing — cheap, available, skilled labor.

Writing for The Financial Times on Monday, Alexandra Scaggs characterizes the current labor market — where wage gains remain meager, job openings are plentiful, employers complain about hiring, but unpaid internships are considered a necessity — one powered by a “cult of meritocracy.” This dynamic roughly says everyone is where they are in life because they earned it and those who can’t catch up are simply not qualified. Therefore, the economy is plagued by a “skills mismatch,” which in some ways more closely resembles a story we tell ourselves to look past rising inequality than an assessment of the labor market.

Cardiff Garcia, a reporter with NPR’s Planet Money, earlier this week highlighted a series of news articles from 2009, ’10, ’11, and ’12 which suggested that employers wanted to hire more but couldn’t find good workers. In these post-crisis years, no one was talking about an economy overheating.

In recent months, the drop in the unemployment rate, the Fed’s clear desire to raise interest rates, and suggestions that a tight labor market was just on the cusp of causing an acceleration in wages and inflation led to some discussion around whether the economy overheating.

But coming off a month in which an industry reportedly starved for workers raises wages less than the national average and 601,000 people joined the labor force, it seems there is still plenty of slack to take out of a labor market clearly still recovering from the post-crisis recession.

And it’s a reminder to take suggestions that America’s economic culture which made the country the world’s most prosperous in the post World War II-era just magically disappeared with a grain of salt.

NOTE: A version of this story was published on July 8.

—

Myles Udland is a writer at Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter @MylesUdland