Back from quarantine in China, Taiwanese fear discrimination at home

Shelly Chen left her ancestral house in Hubei province, the coronavirus epicenter in China, at the end of March after Chinese authorities lifted an order that she stay inside for two months. She rented a private car for the sleepless, 15-hour overnight ride that would get her to Shanghai on time for a rare flight home to Taiwan.

Now she’s in quarantine yet again, in a government-allocated room in a Taipei suburb, where she must stay through mid-April with a toilet, balcony, WiFi, TV, two bottles of water and three meals delivered daily. Once that ends, the single mom can finally see her son and daughter again and reopen her beauty salon franchise, which closed in February because she wasn’t around to run it.

But she feels no elation about her upcoming freedom. Instead, like hundreds of other returnees to Taiwan from mainland China, she fears she’ll be the victim of a damaging social stigma that also has the island’s government concerned.

“You let people know you’re coming from Hubei, or even China, and people freak out,” Chen, 40, said by social media chat from her isolation room. “I plan to see a therapist once I’m released.”

Stigma against people exposed to COVID-19 is hardly unique to Taiwan. But Chen and another 979 people who have returned in waves to Taiwan after 45 to 60 days trapped in Hubei are bracing for more than the usual disapproval.

Taiwanese still associate Hubei with the virus despite the tapering of infections there and because Taiwan’s government itself treats returnees from Hubei more rigorously than it does people flying back from heavily infected Western countries. Folks such as Chen are “seen as people who very much have the virus,” said Huang Kwei-bo, associate professor of diplomacy at National Chengchi University in Taipei.

Taiwan is hyper-vigilant about its coronavirus caseload. Many Taiwanese cite the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, which also originated in mainland China, as reason for caution about pathogens coming from the mainland.

Chen had gone to Hubei in January, before the COVID-19 outbreak there peaked, to see her father after his stroke. Now she’s worried about sidelong glances and whispers behind her back by people who assume she’s infected with the coronavirus.

“There are some people who think that but won’t directly say it’s because you’re from Hubei,” said Chen, who shared screen grabs of chats with fellow returnees warning her about stigma. “Eastern people are polite.”

But the result could still be ostracism at school or work. Chen is debating whether to postpone seeing her children after her isolation ends, even though she cries at the mention of them. She doesn’t want their classmates to find out where their mother came from and blab it around. “I’m afraid I’ll impact them,” Chen said.

A few of her teenage son’s after-school friends already know what his mom has been through. That’s because she has taught him to not to lie, Chen said.

She’s also wondering whether to try to reopen her 3-year-old business. The salon lost about $3,300 during the first month alone of her confinement in Hubei. She fears that many of her customers won’t come back, perhaps suspecting her to be an asymptomatic virus carrier.

The specter of such stigma prompted Taiwan’s health and welfare minister, Chen Shih-chung, to speak out. “We urge our citizens not to discriminate,” Chen told a March 30 news conference. “They’re coming back totally safely and safely going into quarantine centers. We hope the society can accept them.”

But the government itself has treated the Hubei returnees differently, forcing them to stay in government quarantine while most returnees from other places, including heavily infected Western nations, are allowed to self-isolate at home. Just 11 of Taiwan’s total 380 coronavirus cases originated in China, data from the Taiwan Central Epidemic Command Center show. Most entered from Europe, the United States and other parts of Asia.

As of April 2, all but 370 of the returnees from Hubei had been released from government isolation.

Many of those who had traveled to Hubei went in January to see aging parents and in-laws for Lunar New Year. According to Taiwan government figures for 2018, about 339,000 of the island’s 24 million residents were mainlanders married to local Taiwanese.

As the coronavirus caseload in Hubei began rising dramatically, the visitors were banned from leaving apartments and hotel rooms until March while the Chinese and Taiwanese governments bickered over whose airlines would run charter flights and who should be flown back first. The fractious relations between Taipei and Beijing, which regards Taiwan as part of its territory, complicated matters.

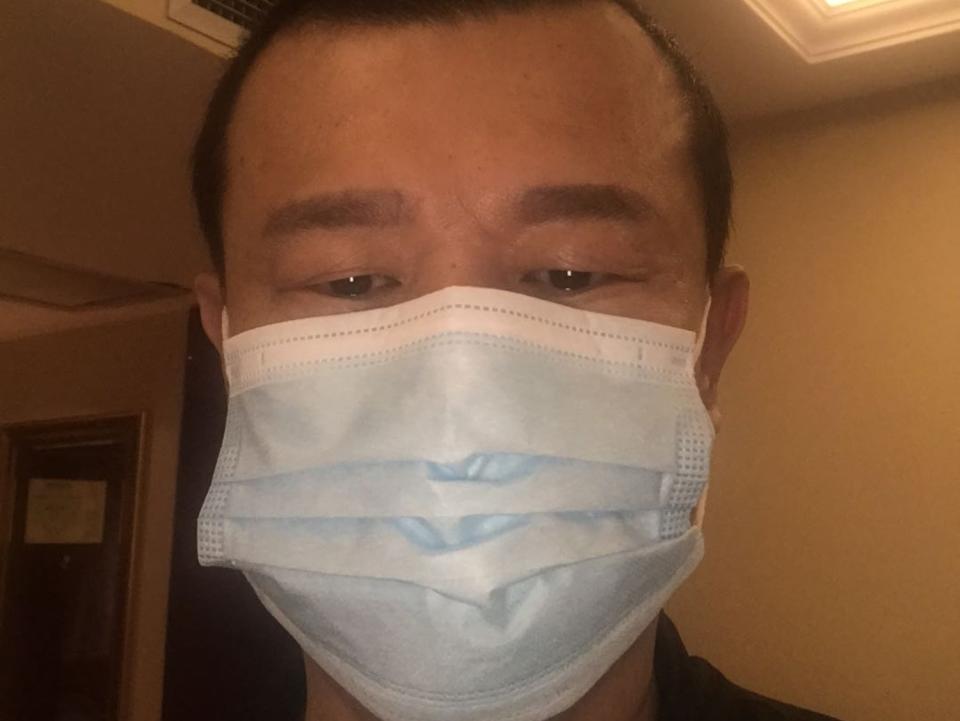

Chen Chi-chuan (no relation to Shelly Chen) is trying to preempt people’s disapproval by masking up and avoiding people who might otherwise avoid him.

The 51-year-old Taiwanese electrical and plumbing contractor lived in a 24th-floor hotel room in Shiyan city, also in Hubei, for 46 days and on March 14 got on a charter flight from Wuhan back to Taiwan. A car took him from Taiwan’s chief international airport straight to an isolation room.

He’s been able to settle past-due accounts for his business and resume work on construction sites without alarming anyone from behind his face mask, a thick white one that rides almost up to the eye sockets.

But neighbors in the housing complex where he and his wife live in the southern city of Kaohsiung know they went to Hubei in January to see his wife’s relatives. The couple are now keeping a “low profile,” Chen said.

When leaving his compound, he steps to the side when approaching his neighbors so that they don’t have to. “They’re afraid, so I keep my distance,” he said. “Taiwanese media have reported this to death, so people feel panicky.”