How China flooded the U.S. with lethal fentanyl, fueling the opioid crisis

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

This is part 2 of Yahoo Finance’s Illegal Tender podcast about the big business behind opioids in the United States. Listen to the series here.

Fentanyl in the form of a highly lethal, synthetic opioid that’s been making its way through the U.S. over the last decade. The largest source of this illicit drug is China.

Ben Westhoff, an investigative journalist and author of “Fentanyl Inc.: How Rogue Chemists are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic,” decided to see firsthand how these drugs are being made.

“I went really deep and tried to learn everything I could about this problem, and that brought me to China,” he said. “I actually went undercover into a pair of Chinese drug operations, including, I went into a fentanyl lab outside Shanghai. And I was pretending to be a drug dealer.”

He continued: “What I learned was that these companies making fentanyl and other dangerous drugs are subsidized by the government. And so when they work in these suburban office parks, for example, the building, the costs for research and development, they have these development zones, they get export tax breaks.”

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season three: The United States of Opioids: Behind a uniquely American crisis

Shoddy regulations on China’s side has led to these drugs entering the U.S. The U.S.-China Business Council stated this is in large part because local governments were prioritizing economic growth and development objectives “above all else,” in addition to “the fragmented nature of China’s administrative system that oversees the production and export of chemical and pharmaceutical products.”

Lax postal service regulations have also contributed to the drug’s rise in the U.S. Initially, those who were shipping fentanyl from China to the U.S. would mislabel the packages and ship them through another country as an extra precaution.

The U.S. government enacted the Synthetic Trafficking and Overdose Prevention (STOP) Act, which was signed into law in October 2018. The legislation mandates that the USPS require being supplied with advanced electronic information for all shipments arriving internationally.

“I think the first thing that really needs to be done is China has to curtail these policies,” Westhoff said. “We can only really control what's happening at home. And we needed to start figuring out: Why are people taking fentanyl? How is it getting into the drug supply? How can people better be prepared to deal with fentanyl when it's discovered? And that's something I put a lot of time and thought into.”

Back in February 2019, the medical journal JAMA published research detailing how the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), pharmaceutical companies, and doctors overprescribed fentanyl as a painkiller from 2012 to 2017. And so the drug — which is sometimes administered when patients with chronic pain are physically tolerant to other opioids — reached more people than it should have and spilled over into the street trade.

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season three: The United States of Opioids: Behind a uniquely American crisis

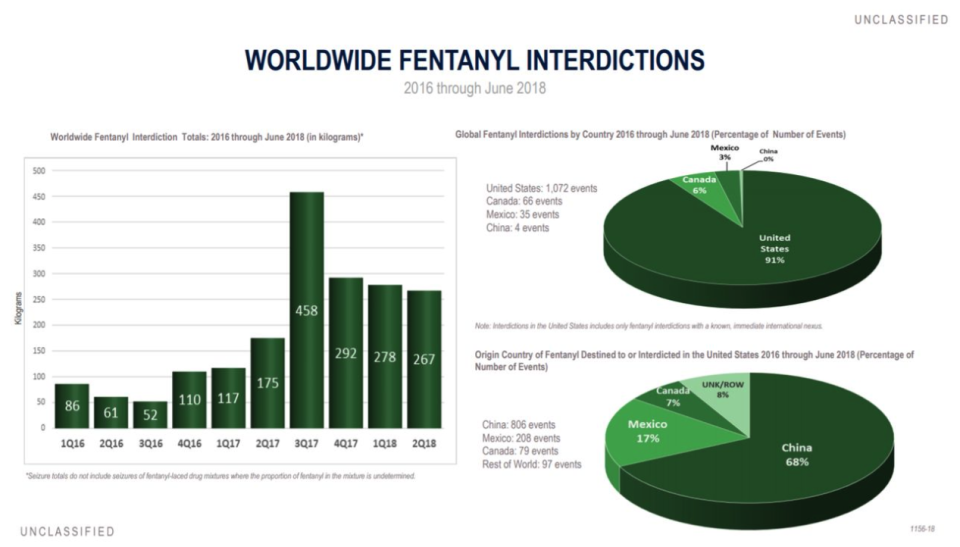

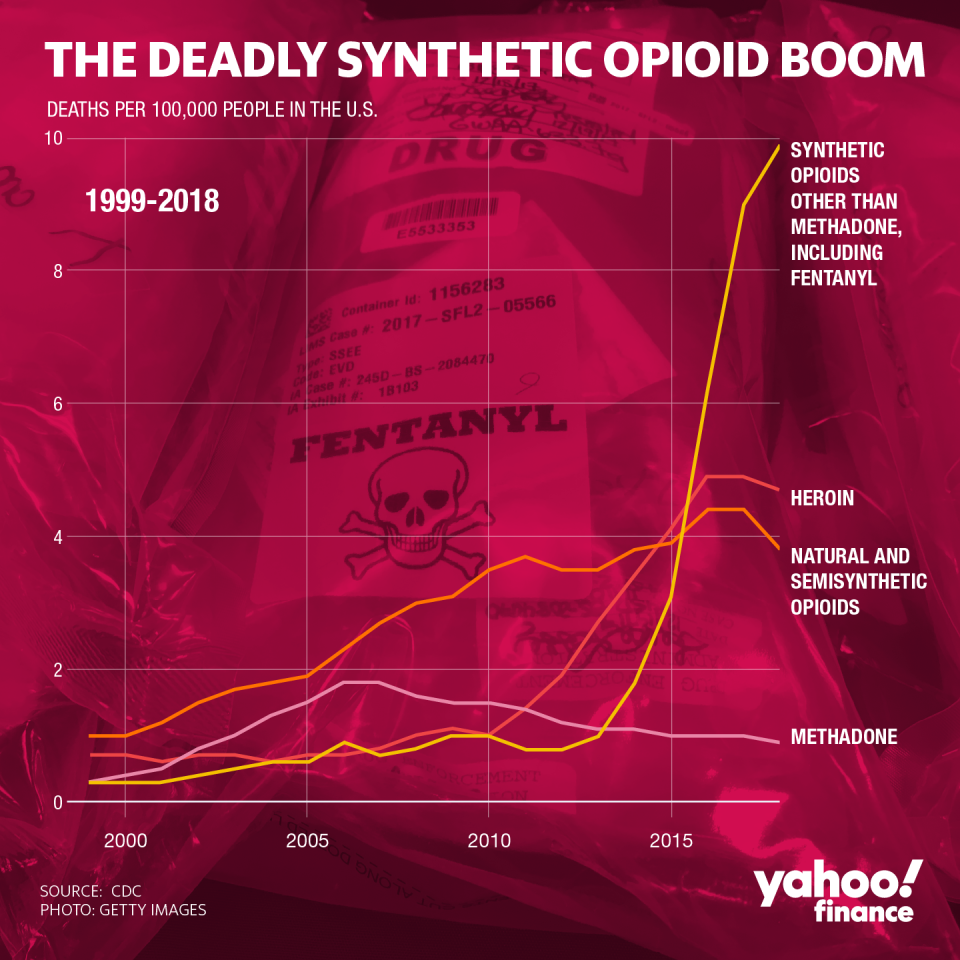

The street trade is where China’s responsibility lies, Westhoff said. It’s part of the reason why between 2016 and 2017, synthetic opioid overdose deaths, including fentanyl, increased by 45%. Data from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) shows that “synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, are now the most common drugs involved in drug overdose deaths in the United States.”

“At heart, I think this story is really about global capitalism,” Westhoff said. “And as much as we might want to say, it's the evil Chinese leaders who are inflicting this horrible poison on Americans, really it's the same things that drive global capitalism. The internet age, these drugs are sold on the internet, the speed of shipping has been increased.”

He continued: “The giant China and the U.S. normalized trade relations in the year 2000, and that cutting down barriers to trade. All of these things are fueling the drug crisis, and people who don't even realize they're involved with it, like the UPS workers, for example, the people driving these barges going across the ocean that are filled with fentanyl, and they don't even realize it. And so it's such a complicated problem that, at the end of the day, it can all be traced back, like everything else, to profit motive.”

Illegal Tender by Yahoo Finance is a podcast that goes inside mysteries in the business world. Listen to all of season three: The United States of Opioids: Behind a uniquely American crisis

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

Full transcript:

Adriana Belmonte: This is Illegal Tender, season three. I'm Adriana Belmonte. Data has shown that the opioid crisis will have cost the US economy more than $819 billion, from 2015 through 2019. To put that into perspective, that's over five times the cost of weather and climate disasters between 2016 to 2018. Between 2016 and 2017, synthetic opioid overdose deaths, including fentanyl, spiked upward by 45%. Fentanyl can be 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. And according to the National Institute of Health, synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, are now the most common drugs involved in drug overdose deaths in the United States. So who is it that's responsible for this fentanyl surge? Is it our pharmaceutical companies? The drug cartels in Mexico? Or chemistry labs out of China?

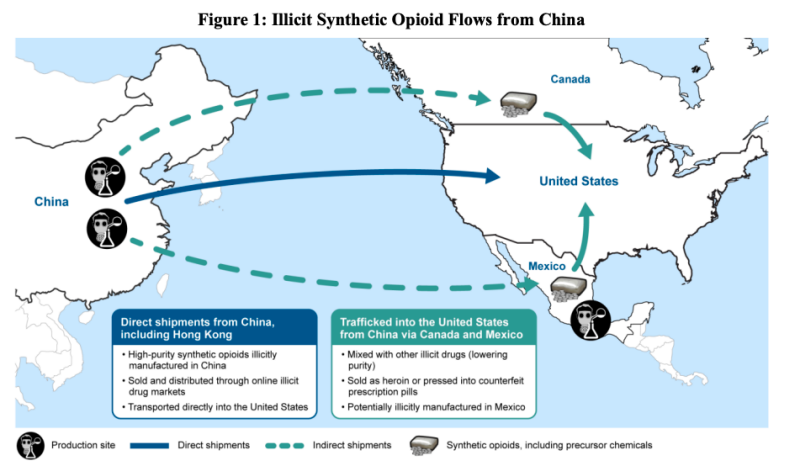

Ben Westhoff: Yeah, we do think of the Mexican cartels as supplying almost all the drugs that Americans have. And that's true of heroin, meth, cocaine, and even marijuana to a large extent. But these new drugs, particularly fentanyl, they're made in the lab and they're all made in China. And so, what China does is these are, these are chemists, these are in some cases legitimate chemists and companies who make these drugs, and sometimes they're even made legally by Chinese law. There's these different types of fentanyl, different types of new drugs. And then they are shipped to the Mexican cartels, who distribute them in the US. Sometimes fentanyl and other drugs made in China are actually shipped through the US mail directly to consumers. And so you have the US Postal Service, FedEx, UPS, all unwittingly serving as drug couriers to Americans.

Adriana: A 2019 study from the Cleveland Fed, found that prescription opioids accounted for 44% of the decline in labor force participation among men between 2001 and 2015. So look at it this way. The reason why almost half of America's men are out of the workforce is because of opioids. So where are these drugs actually coming from? For fentanyl, it's mostly coming from China. Ben Westhoff detailed it in his book, Fentanyl, Inc.

BW: I went really deep and tried to learn everything I could about this problem, and that brought me to China. I actually went undercover into a pair of Chinese drug operations, including, I went into a fentanyl lab outside Shanghai, and I was pretending to be a drug dealer.

BW: It was all very harrowing and my wife and family were concerned for my wellbeing. But in the process I learned that these are normal companies. I was expecting, like I said, an underground sort of drug lair, with guys holding AK47s guarding the doors. But it wasn't like that. The lab I visited looked like a suburban office park. And what I learned was that these companies making fentanyl and other dangerous drugs are subsidized by the government. And so when they work in these suburban office parks, for example, the building, the costs for research and development, they have these development zones, they get export tax breaks. And so, I think the first thing that really needs to be done is China has to curtail these policies. We can only really control what's happening at home. And we needed to start figuring out, why are people taking fentanyl? How is it getting into the drug supply? How can people better be prepared to deal with fentanyl when it's discovered? And that's something I put a lot of time and thought into.

Adriana: Now, when you were in China, did you know, is fentanyl a big issue there as well in terms of addiction, or is it just being taken out of China to other places?

BW: I got to learn a lot of interesting things about drug culture in China. And one thing that really shocked me first of all was that almost nobody uses marijuana. Almost nobody uses cocaine. The drugs of abuse in China tend to be things like meth and heroin. And even ketamine is very popular, but fentanyl is not a problem in China. China does not have a fentanyl crisis nearly the scope that the US does, or Canada, also has a really big problem. And so to a lot of people, this is why China hasn't really cracked down on its fentanyl industry, because its own people aren't dying from it. And so the way the Chinese government works is, fentanyl is illegal there, but it's not so much just the laws on the books, it's what resources the government dedicates to cracking down on different problems. And so when it comes to meth, which is a huge problem among Chinese citizens, the government has really focused on trying to stamp it out, take drug dealers down, disrupt operations. But when it comes to fentanyl being made there, that's just not the case.

Adriana: So, I know you talk a lot about this in your book, but for people who aren't familiar with it, what was it that took you to China to begin with, and what made you want to go to this particular place in China?

BW: I heard so much that fentanyl came from China, and I wanted to know, how are people ordering this? And so I just Googled "buy fentanyl in China" and I was shocked when just dozens and dozens of different companies, web addresses came up, and you could just directly email the sales people. And so I was in contact with a bunch of them. I made a fake email address and I said, "Tell me more about your company." And sometimes I would get up at four in the morning to do Skype conversations with salespeople in places like Guangdong and Shanghai and Wuhan. And we talked about drugs. But I also talked about, what's life like as someone who was selling these awful chemicals? And I got to really know the human side of the people working for these companies as well.

Adriana: Now, did you ever feel like your life was in danger while you were in infiltrating these labs?

BW: It was definitely a scary experience. One thing that I took a little bit of comfort in, is that these people running these labs really are business people and so they don't, gun control is very strong in China. Even the criminals don't tend to have guns. And so I was, however, really worried about the Chinese government because I wasn't there on a tourist visa. Excuse me, I was there on a tourist visa. I wasn't there on a journalist visa, because I knew if I got a journalist visa they wouldn't let me do the things I wanted to do. And so, but I've since talked with the US department, the State department, and they are warning me, don't go back to China, what you did is grounds enough to be put in jail. And so I am taking their advice.

Adriana: So, how did they find out? It was once the book came out that they found out about all the undercover work you did?

BW: Well, I don't even know if they do know. That's the thing. They might have never have heard of me, I might be top of their most wanted list. I just, there's no way to know, and so I can't take my chances.

Adriana: And I know that there were some people that you had formed, I guess, a cordial relationship with while you were there. Have you heard from any of them since then?

BW: I haven't heard from the sales people, but I have learned a lot of information about this company that I wrote about in great detail. The company is called [Yuan Chung 00:00:07:29]. They're based in Wuhan, huge portion of the book, my book, Fentanyl, Inc., is dedicated to, how did this company come to be? They came to sell more fentanyl ingredients than any company in the world. I did this deep dive about the CEO, how he amassed his fortune, how they came to start selling these chemicals. And I ended up in China going to their sales floor, with hundreds of sales people, young people just out of college, behind laptops, using social media to sell this stuff. And I ran the numbers on this company and they're making a ton of money. But since then, since the book came out, there has actually been a big fire at their factory and it came out the exact, that the fire happened the exact same time when my first excerpt for this book came out, it was in the Atlantic magazine and it was all about this company.

BW: And so right when that happened, there was a huge fire at the factory, and the police said in the article, that arson had not been ruled out. So I am curious to know what's going on behind the scenes there.

Adriana: And what was some of the things that you saw while you were infiltrating this Chinese lab? I know you said that the place looks very normal for a place that's making illegal drugs, but what were some of the other things that you witnessed?

BW: Yeah, well I go into detail in my book, but this place that was selling the fentanyl precursors was, in a way, it wasn't all that different than the Yahoo offices here. They had their own chef, they had this big canteen, they tried to promote team-building. It was very corporate in its on the way. They work long hours. They had to work Saturdays, and it was actually in an old hotel, and so all the employees lived in the hotel as well. And that was actually a sales point to try to get people to work there, because room and board were provided. So, I'm not saying you should give up your jobs here and move there, but there were similarities.

Adriana: And what do you think was the most surprising thing about your experience there in China, that you weren't expecting?

BW: Well, I loved going to China. I loved being there and it makes me sad to think I can't go back. But, at heart, I think this story is really about global capitalism. And as much as we might want to say, it's the evil Chinese leaders who are inflicting this horrible poison on Americans, really it's the same things that drive global capitalism. The internet age, these drugs are sold on the internet, the speed of shipping has been increased. All, the giant China and the US normalized trade relations in the year 2000, and that cutting down barriers to trade. All of these things are fueling the drug crisis, and people who don't even realize they're involved with it, like the UPS workers, for example, the people driving these barges going across the ocean that are filled with fentanyl, and they don't even realize it. And so it's such a complicated problem that, at the end of the day, it can all be traced back, like everything else, to profit motive.

Adriana: Also in your book you talk about how these Chinese labs are manufacturing it. So, can you go into a little bit more detail of how it's making its way into the US and what's happening before it gets to the US as well?

BW: Yeah, we do think of the Mexican cartels as supplying almost all the drugs that Americans have. And that's true of heroin, meth, cocaine, and even marijuana to a large extent. But these new drugs, particularly fentanyl, they're made in the lab and they're all made in China. And so, what China does is these are, these are chemists, these are in some cases legitimate chemists and companies who make these drugs, and sometimes they're even made legally by Chinese law. There's these different types of fentanyl, different types of new drugs. And then they are shipped to the Mexican cartels, who distribute them in the US. Sometimes fentanyl and other drugs made in China are actually shipped through the US mail directly to consumers. And so you have the US Postal Service, FedEx, UPS, all unwittingly serving as drug couriers to Americans.

Adriana: So you're talking about the postal service, how it's being used as couriers here? Should they be held responsible for this? Does the blame go to China, these labs, where does the primary responsibility lie for getting to the root of this issue?

BW: Right. Well, there is a lot of blame to be spread around. I talk about, in Fentanyl, Inc., the case of an 18-year-old boy from North Dakota named Bailey Hanke, and he overdosed and died from fentanyl that he got from just the local neighborhood high school drug dealer. And that guy got it off the dark web. And so, the dark web, you probably know, is the disguised internet protocol that has all these drug marketplaces. And the man who was selling via the dark web was based in Portland, Oregon. And then he had a connection, and another connection, and finally it could be sourced back to China. And so the DEA and other departments of US law enforcement prosecuted people on every step of this drug ladder, except who they couldn't prosecute were the Chinese chemists who actually made the drug.

BW: And that's because China doesn't extradite criminals accused of US crimes. And so, when we're talking about who's to blame for the fentanyl crisis, we've got to start at home. Why is the demand so high? But in terms of China, and that's what I really focused on in my book in large part, China is not only doing a poor job stopping fentanyl from getting exported to the US, they are even encouraging it in a lot of ways, through the tax code and all these complicated ways that add up to a really troubling situation.

Adriana: So now we know how it's getting in, but how is it spreading? Why is fentanyl and other opioid use so rampant in the United States? One thing that Ben pointed out, that's worth noting, is that fentanyl is not a drug that people are seeking out. Meaning it's often being accidentally consumed by being cut into other drugs, particularly heroin and prescription tablets. So essentially someone who is using drugs purchased from unreliable sources is often at risk of trying fentanyl, and by proxy, at high risk for overdose, because just a small amount of fentanyl can have deadly consequences.

Ryan: So, my name is Ryan Marino. I'm an emergency physician, so I work in the emergency room, and I'm also a medical toxicologist.

Adriana: When it comes to patients overdosing and receiving treatment. We wanted to speak to a professional.

RM: And certainly prescription opioids were over prescribed, were a big factor leading into the problem we're in now, but this is not prescription fentanyl. Fentanyl was never really one of the ones that was being prescribed heavily, even though it is an opioid we use medically. But fentanyl is just a nice synthetic opioid that people can make at home. You can make it in a lab very easily. People can order the precursor parts on the internet. You can ship it in bulk from places like China, and then make it somewhere like Mexico, or even in the United States now. And so that's where fentanyl is coming from. And the reason for that is because, not because of prescriptions either, but because heroin has been so effectively targeted by criminal justice efforts, and supply side interventions, that there isn't really enough heroin production anymore to match the rate of people who were using heroin before.

RM: So, fentanyl is made into a powder that looks very similar to heroin and then it's usually sold as heroin, in the same way, used the exact same way. But fentanyl itself is about 50 times more potent. So, whereas street heroin used to be about 50% pure heroin, if you think of that, fentanyl is about 1% pure to get the same dose. And so a change in percentage of just 1% purity can give someone twice the dose that they would be expecting. And that's where all these overdoses are coming from.

RM: And then another big misconception here, since I did say that this is not medical fentanyl, is that even though it isn't medical fentanyl, it's being sold in street drugs, and people refer to this as illicit fentanyl. It's the same molecule. It is the same exact drug as the fentanyl we use in the hospital, that people have been using day in and day out for the past almost 50 years.

Adriana: There are countless misconceptions about fentanyl, and the use of opioids in general, but there are even more about the people who turn to these drugs to begin with. Oftentimes addiction begins with simply experimenting. It doesn't just happen overnight. Here's what Andrew [Burki], the chief public policy officer at the Hanley Foundation had to say.

Andrew: I wouldn't classify what I was doing as a substance use disorder. I would classify it as experimentation and substance misuse. But once those opioids hit your system, when I started really getting into substances, that's when I sort of took off, and of course I ended up on heroin. So there are no, there's certainly, you have 200 million Americans plus that are moderate with alcohol consumption. You have a lot of people even that moderate with marijuana consumption. There are no social heroin addicts, it's heroin users rather. You are either using heroin or you're not using heroin. There's no gray, and especially with fentanyl, as you cover extensively. No-one would, from a recreational standpoint, roll the dice on potentially dying every single time they use, which is why we have 70,000 Americans dying each year now. We just, this decade that's about to wrap up in whatever, 10 days or so, less than two weeks, is, we lost half a million Americans to overdose. It's just an unacceptable. That is fundamentally unacceptable.

Editor’s Note: After the time that this podcast was recorded, Andrew Burki was arrested on three counts of sexual assault, aggravated assault on a domestic violence victim, and possession of a firearm magazine capable of holding more bullets than allowed under New Jersey state law.

Adriana: In our third and final episode of this season, we learn about the stigma associated with drug use and the consequences that come with it. Why do you think that there is this stigma still towards losing somebody to substance use disorder?

Cheryl Juaire: Because I think people look down on you. "Your child died from an overdose. He must have been a bad kid. You must have raised him wrong. You must have done something wrong." And that's the mentality of thinking, unless it's touched them, really touched them. Unless they know somebody, they're just going to be ignorant to it, unless they come up and say, "Tell me about that loss. What happened?" And that's when we can educate them. That's when it will change things. But the ones who have been in the throes of addiction, the ones who have lost their children to addiction, we all know, and we all get it.

Adriana: Illegal Tender is made by Yahoo Finance, at our studios in New York City. This episode was written and hosted by me, Adriana Belmonte. Illegal Tender was created, edited, and produced by Alex Sugg. Thank you to Ben Westhoff, Ryan Marino, Andrew Burki and Cheryl Juaire for contributing to this story. Westhoff's book, Fentanyl, Inc,. How Rogue Chemists are Creating the Deadliest Wave of the Opioid Epidemic, is available now from Grove Atlantic. If you enjoy this podcast, head over to Apple podcasts and leave us a five-star rating, and review it for the show. Until next time, thank you for listening to Illegal Tender.

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts

Adriana is an editor and reporter at Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @adrianambells.