China's Underground Market for Chips Draws Desperate Automakers

(Bloomberg) -- In her two-bedroom apartment on the outskirts of Chinese tech hub Shenzhen, Wang woke to a deluge of messages. One read: “SPC5744PFK1AMLQ9, 300 pc, 21+. Any need?”

Most Read from Bloomberg

China Stocks Slide as Leadership Overhaul Disappoints Traders

Wall Street Is Heading to Saudi Arabia as US Oil Spat Simmers

Korean Air Plane Overruns Runway While Landing in Philippines

Within minutes, the 32-year-old was at her computer in the living room, hurriedly clearing away empty packets of instant noodles and pulling up a spreadsheet. The code referred to a chip produced by NXP Semiconductors Inc. and used in a car’s microcontroller unit. The sender of the message was trying to find a taker for the 300, made no earlier than 2021, that had come into his possession.

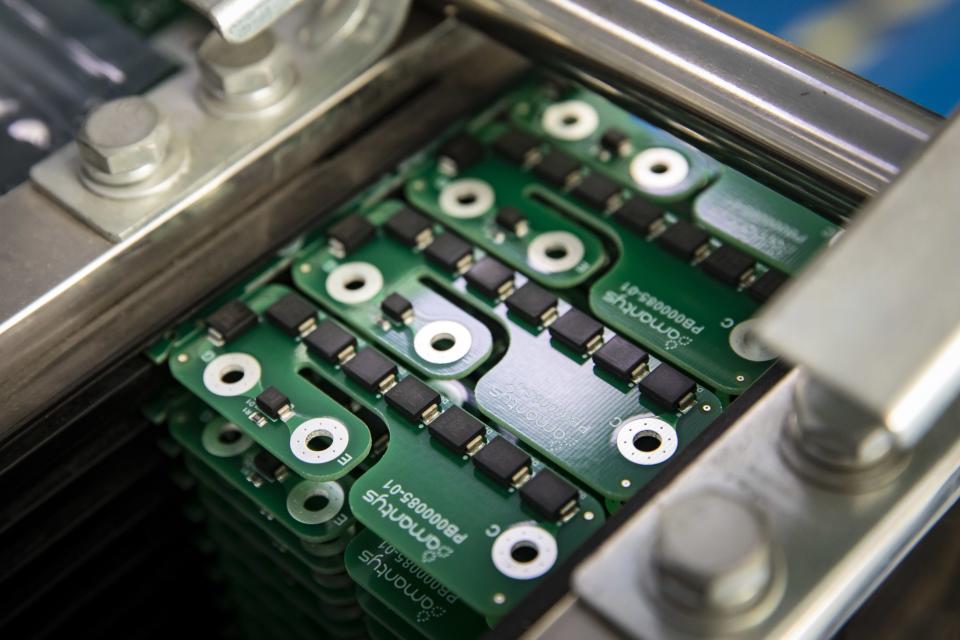

Neither Wang, nor any of her six-member team, are legitimate chip dealers. Freelance brokers like her used to be bit players in China’s semiconductor market, but they became increasingly important in late 2020 when a worldwide shortage of chips began to disrupt supplies of everything from smartphones to vehicles. Now, they’ve formed a massive gray market — an opaque forum populated by hundreds of middlemen and riddled with second-hand or out-of-date chips where the cost of acquiring just one can run to 500 times its original price. The situation is most acute with chips destined for cars, which are becoming more like computers on wheels as the industry is revolutionized. The US’s recent chip technology export curbs will only make the shortages worse, encouraging underground activity, the head of China’s major car association said.

“Recent US sanctions have introduced another round of panic to the market and disturbed the supply of both entry level and more advanced chips,” China Passenger Car Association Secretary General Cui Dongshu said last week. “Distribution channels and the prices of chips are messed up.”

Opportunists the world over have seized on the chips shortfall, jacking up the price companies pay for the crucial circuital components. But a lack of regulation and soaring demand — China is by far the biggest global market for cars and is in the throes of a new wave of electric vehicles — mean under-the-table deals are more widespread here.

In scores of interviews with more than a dozen people involved in this world, all of whom declined to be identified because of the sensitive nature of what they’re doing, Bloomberg News pieced together how the complicated network operates. Substandard chips have so infiltrated the supply chain, many brokers say, that car quality, and worse — safety — is at risk. Should a fraudulent chip fail in the ABS brake module of a vehicle, for example, the consequences could be life threatening.

Leading German auto-parts supplier Robert Bosch GmbH received several requests from Chinese carmakers to process vehicle components using chips that had been sourced on the gray market by the companies themselves, people familiar with the matter said. Bosch ultimately turned down the requests, believing the chips could risk the integrity of its own parts. One automaker requested Bosch work with gray-market semiconductors whose price had soared during a Covid outbreak because Bosch's Malaysian supplier had to cease production of the chips, used in Bosch’s ESP (Electronic Stability Program) product. (Electronic stability programs work with a car’s antilock braking system to detect skidding movements and counteract them.) Bosch refused, one of the people said. A representative for Bosch referred to an interview that Xu Daquan, its executive vice president of China, did in September, in which he said the chip shortage “is not expected to be solved in the next year.” The company declined to comment further.

While operations like Wang’s are legal in that they’re registered companies and pay taxes, the provenance of chips bought and sold on the gray market can be difficult to assess. Chips can come from questionable channels — backdoor sales from authorized agents, who may have, intentionally or otherwise, placed surplus orders with a manufacturer, or legitimate companies that are selling excess chips for a profit, violating agreements with the original chipmakers. Some of the brokers also try to juice profits by hoarding and price gouging, behavior that violates Chinese regulations and that local authorities have sought to crack down on.

According to Wang, who asked to only be identified by her last name, the “conventional system whereby auto suppliers place an order through an authorized agent and wait for distribution from an original chipmaker no longer works.”

Semiconductors required for microcontroller units have been among the hardest to source and command the most eye-watering prices, reporting by Bloomberg found. That’s because they’re used in so many parts of a car, from electronic braking systems to air conditioning and window control units. In a world where chips are becoming smarter and smaller, they require much less advanced technology to manufacture and therefore command smaller margins. As demand surged during the pandemic, chipmakers switched production to more profitable semiconductors for use in consumer electronics or medical devices, greatly reducing the supply of microcontroller unit chips.

Carmakers responded in different ways. Toyota Motor Corp. and Volkswagen AG largely just pulled back on production and deliveries, while Tesla Inc. found workarounds, developing new software that allowed the pioneering electric vehicle maker to use alternative semiconductors. In China, the cutthroat nature of the local market — there were some 200 registered EV makers, alone, last year — saw domestic players in particular embrace the chip gray market.

All three of China’s main, US-listed EV upstarts — Nio Inc., Xpeng Inc. and Li Auto Inc. — have tried to buy chips via these unauthorized agents, middlemen who are classified as such because they don't have permission from the original chipmakers to distribute their products, according to people familiar with their activities. In fact, almost every Chinese carmaker except the country’s biggest EV manufacturer BYD Co., which makes its own chips, has attempted to source semiconductors this way, the people said.

Beijing-based Li Auto, known for its flagship Li One sports utility vehicle, paid the equivalent of over $500 to one broker for a single brake chip that cost about $1 before the pandemic, people familiar with the matter said.

In an interview with Bloomberg in July, Li Auto President Kevin Shen said the company was still struggling with some key chip supplies and expected to continue to face problems given the number of semiconductors required by tech-laden EVs. A representative for Li Auto denied the company paid 500 times the original price for a chip, but declined to comment further for this story. Spokespeople for Nio and Xpeng declined to comment.

The gray-market trade mainly takes place online, in WeChat groups and over email, but trades also sometimes happen at physical marketplaces like the Saige (SEG) Electronics Market Plaza Huaqiangbei in Shenzhen, where brokers have been known to bring chip samples in knapsacks to secure orders. And it hasn’t escaped regulators’ notice. In August last year, the government launched a probe into possible price manipulation, fining three brokers a total of 2.5 million yuan ($350,000) for selling car chips “with a substantial markup.” But in a market where automakers are so desperate for supply they’re willing to pay multiple times what a chip is worth, that sort of penalty isn’t much of a deterrent.

China’s secondary chip market didn’t spring up overnight. It existed before the semiconductor crunch, but with so many people sensing an opportunity to profit, it’s ballooned. “Everyone’s a speculator,” one of the unauthorized brokers interviewed by Bloomberg said.

While in most cases, brokers get sales commissions, the most profitable, albeit risky, way to make money is to try to predict demand and hoard chips, offloading them later for huge markups. It requires good luck, plenty of cash and lots of guanxi, the Chinese system of social networks and influential relationships that facilitates business dealings. If a bet goes wrong, it could mean bankruptcy. Reports of overnight millionaires, and suicides, aren’t unheard of.

Relatively low barriers to entry mean that “anyone with sources can be a broker,” according to a manager at a Shenzhen-based semiconductor trading company. “Companies like us may have some advantage in terms of product reliability but the opportunists have muddled the market. We had no choice but to join it.”

Brokers with better guanxi are always the first to get information and enjoy priority when it comes to securing orders at an advantageous price. Bribery isn’t commonplace, but it’s also not unheard of. Chip supplier employees are sometimes paid to steal chips that have been allocated to an automaker, people familiar with the matter said. Aware of such misconduct, one Chinese car company has begun dispatching staff to oversee delivery of their semiconductors. An employee then sits alongside the parts maker's production line to make sure that the chips are used in their products and any left over are properly locked away, according to a person familiar with the arrangement.

A sale typically goes to the party willing to pay the highest price but sometimes, having better guanxi trumps that. Instead of paying by installments — the conventional way of automotive chip supply — all transactions in the gray market are paid in cash.

To prevent others from tracing where chips have come from, intermediaries often scrub labels or information on packaging. Though completely fake chips aren’t commonly seen because of the technical expertise and machines required to make them, several automakers have fallen into the trap of unwittingly buying second-hand chips that have been removed from discarded auto parts and sold as new, people familiar with the matter said.

“Reused chips can cause problems because they might have been built for too small a temperature range, for example,” said Phil Koopman, an associate professor of electronic and computer engineering at Carnegie Mellon University. He’s been involved with automotive chip design and safety for around 30 years. “Just as important is that chips wear out over time, so reused chips might fail much sooner than expected. I’m not aware of any practical way to detect this problem other than re-doing factory qualifications for temperature ranges and reverse engineering to check for signs of repackaging.” These chips can easily slip into vehicles unnoticed, he said.

The risk of that happening has spawned another grass roots industry: chip quality inspectors. Typically former employees of chip companies or authorized agents, they claim to have the ability to verify labels and packaging and even to be able to X-ray the interiors of the chips. Business consultants are also joining the fray, vetting brokers for carmakers and running business credibility checks.

In a bid to accelerate the procurement process considering how volatile prices are, several Chinese automakers have appointed people internally to oversee the direct purchase of chips from brokers. In some cases, chip prices may change overnight, every other hour, or even after a purchase inquiry is made. If carmakers have well-oiled systems in place, the time from quotation to delivery can be as fast as 24 hours. “Chinese automakers are more flexible in finding the solutions to ease the chip supply,” Wang Bin, an automotive analyst at Credit Suisse Group AG, said at a briefing in May.

However faced with such immediate demand for chips, almost all car companies have chosen to compromise, at a minimum by accepting chips with older production dates. Before Covid, automakers typically only used chips produced in the past 12 months; now many are using semiconductors made four or five years ago, so long as they’re the right type.

Older chips that have never been used but that have been well stored “can be acceptable depending on the circumstances,” said Koopman at Carnegie Mellon. One hitch is that older chips might have design defects — ‘errata’ that have subsequently been corrected in newer versions. “Newer vehicles might not ever have been tested to see if they can survive the defects in the older chips,” he said.

The PCA’s Cui said it’s impossible to detect what used or refurbished chips may be circulating inside cars and as such, regulators have a difficult time supervising gray market transactions. Whether it will lead to safety issues is hard to say but “at the very least it’s not fair to consumers because they’re not informed about it,” he said.

China’s State Administration for Market Regulation has said hoarding chips violates several articles under national price law. “Brokers are taking advantage of the imbalance between the supply and demand of auto chips in China,” it said, adding that such behavior could lead to “panic stocking and worsen the imbalance.” China’s Ministry of Information and Technology and its Ministry of Transport, each of which has a safety regulation unit, didn’t respond to requests for comment. There haven’t been any accidents publicly known to have been caused by faulty chips purchased on the gray market.

While global automakers like Toyota and General Motors Co. say the chip shortfall is showing signs of easing, Fitch Ratings Inc. doesn't see a full recovery until 2023, due to the combination of semiconductor shortages, shipping delays and Covid Zero lockdowns, especially in China. That means automakers are increasingly being pushed to switch up their long-held strategy of only holding enough inventory for the immediate future and building in buffers, according to Kenny Yao, a director at Shanghai-based auto industry consultancy AlixPartners.

“An automaker has to think about three questions,” Yao said. “In the short term, can it find a good replacement for certain types of chips? In the mid-term, can it alter its design to allow for more flexibility in semiconductor parts? And in the long term, can levels of integration be raised to combine the functions controlled by several basic chips into one advanced one?”

Until that point, business should remain brisk for Wang.

While her company has a small office about 30 minutes’ subway ride away, she’s so busy that she rarely goes in, spending most of her waking hours hunched over her laptop at the dining room table or answering WeChat messages from her bedroom. When things get really crazy, she has to stockpile food. “We’ve become the go-to guys for urgent supplies,” she said. “It keeps our clients’ production lines running.”

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

The Private Jet That Took 100 Russians Away From Putin’s War

Female Bosses Face a New Bias: Employees Refusing to Work Overtime

Europe’s Most Valuable Tech Company Tries to Avoid the Chip War

Strategies to Avoid Workplace Conflict With the Return to Office

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.