How the late Christopher Tolkien preserved his father's Middle-earth writings

“In my ninety-third year this is (presumptively) my last book in the long series of editions of my father’s writings,” Christopher Tolkien wrote in the 2017 preface to Beren and Lúthien, a presentation of his father’s story about a mortal man’s star-crossed romance with an immortal elven princess. As it turned out, he was wrong; a year later, in 2018, Christopher published one more volume, The Fall of Gondolin, which he described as “the third of my father’s ‘Great Tales'” (along with Beren and Lúthien and The Children of Húrin before it). But this week, the Tolkien Society announced that Christopher had died at the age of 95, marking the end of an era for Middle-earth.

Christopher Tolkien has died at the age of 95. The Tolkien Society sends its deepest condolences to Baillie, Simon, Adam, Rachel and the whole Tolkien family. pic.twitter.com/X83PTx4b7x

— Tolkien Society (@TolkienSociety) January 16, 2020

When the elder Tolkien died in 1973, he left behind a trove of notes, drafts, and unpublished writings. Readers across the world had fallen in love with The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, but one of the reasons those novels feel so grand and magical is the constant references to the greater mythology of Middle-earth. Aragorn and Arwen, who are in love despite their differences as mortal man and immortal elf, are often compared (by both themselves and others) to Beren and Lúthien, but their full story is not elaborated. One of the most memorable scenes in The Lord of the Rings features the wizard Gandalf’s confrontation with the demonic Balrog deep in the mines of Moria; how did such a creature come to be? If Sauron is such a grave threat to the world, why do powerful elves like Arwen’s father Elrond seem so bored with fighting evil? Tolkien had answers to all these questions, but was unable to process them into a single, comprehensible volume before he died.

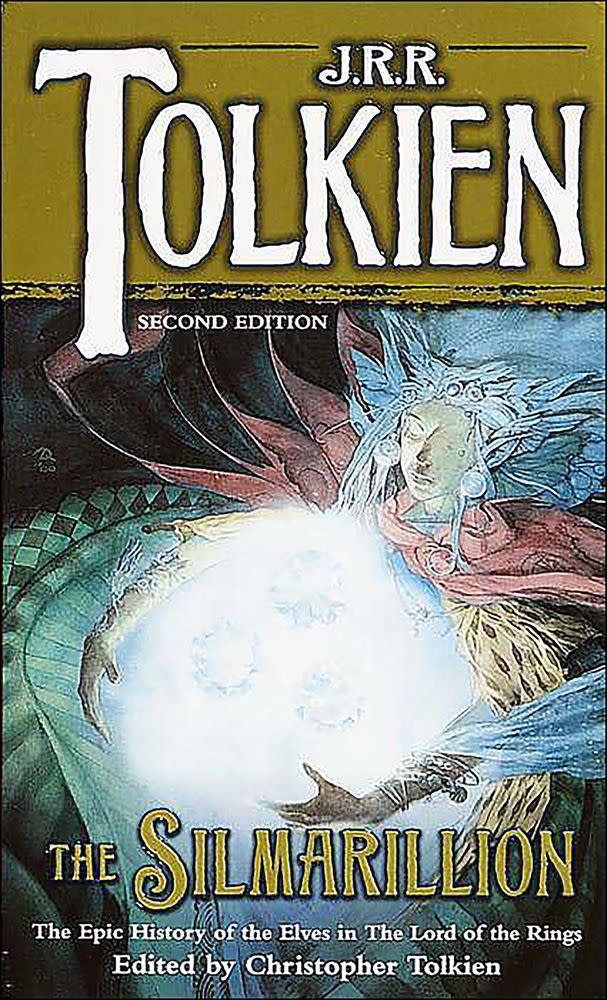

The task, therefore, fell to Christopher, whom Tolkien appointed as the executor of his literary estate. Christopher spent four years going through these writings until he was able to publish a streamlined narrative of Middle-earth’s so-called “Elder Days,” from the literal creation of the world through the fall of Sauron’s evil predecessor Morgoth and even into the Atlantis-like sinking of Númenor, the great human kingdom of which Aragorn is a descendant. The reason this task was so difficult, Christopher would explain over and over again, is that his father spent much of his own lifetime working on it, and it changed and grew as he did. In the process, Middle-earth very much came to resemble the kind of ancient mythology that Tolkien sought to create for his native England.

“My father came to conceive The Silmarillion as a compilation, a compendious narrative made long afterwards from sources of great diversity (poems, and anals, and oral tales) that had survived in agelong tradition; and this conception has indeed its parallel in the actual history of the book, for a great deal of earlier prose and poetry does underlie it, and it is to some extent a compendium in fact and not only in theory,” Christopher wrote in the 1977 foreword to the first edition of The Silmarillion. Though the book has a reputation as a difficult read, we here at EW compiled a list of reasons why it is actually awesome and worth exploring in honor of its 40th anniversary in 2017.

But one volume was far from enough. In order to show how he had processed his father’s writings and ideas, Christopher went on to publish The History of Middle-earth in 12 volumes over 13 years. He then went from the macro scale to the micro, expanding on three specific stories from The Silmarillion in the aforementioned volumes: The Children of Húrin, Beren and Lúthien, and The Fall of Gondolin. Each book tells not just its titular tale, but every single version of the tales as they evolved over time in Tolkien’s conception. Beren and Lúthien, for example, contains the earliest version of that story, in which Lúthien was named Tinuviel, Beren was also an elf, and Sauron took the form of Tevildo, Prince of Cats. There are also versions written in poetic verse, and extracts from other tales. Each of the three books was accompanied by illustrations from Alan Lee, who also provided much of the concept art for Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings films.

“I think working on these books gives [Christopher] a new lease on life,” Lee told EW in 2018 when The Fall of Gondolin was published. “He threw himself straight into The Fall of Gondolin. We didn’t actually know about it until this time last year there was a potential other one. I’m sure he’ll be happy to have those books in his hand. This particular journey is completed.”

Christopher was never a fan of adaptations (“The chasm between the beauty and seriousness of the work and what it has become has overwhelmed me,” he told Le Monde in a rare 2012 interview, quoted in Ian Nathan’s Peter Jackson & The Making of Middle-earth) but if there’s one thing the Lord of the Rings movies share with the books, it’s the idea that all journeys must eventually come to an end. Thanks to Christopher’s lifelong efforts, the history of Middle-earth is now complete and open to the interpretation of future generations, in the manner of all mythologies.

Related content: