Cornstarch is a Powerful Tool That Must Be Used Responsibly

Santa isn’t real. Neither is Harry Potter, the Tooth Fairy, or flattering white pants. But we do have some magic left in this world: cornstarch. Seriously, what can’t cornstarch do? Not only is it the ingredient responsible for crispiness in so many instances—from baked chicken wings to deep-fried chicken thighs to sautéed shrimp to pan-fried cubed tofu—but it also makes cakes and cookies tender and soft. Talk about working both sides of the aisle.

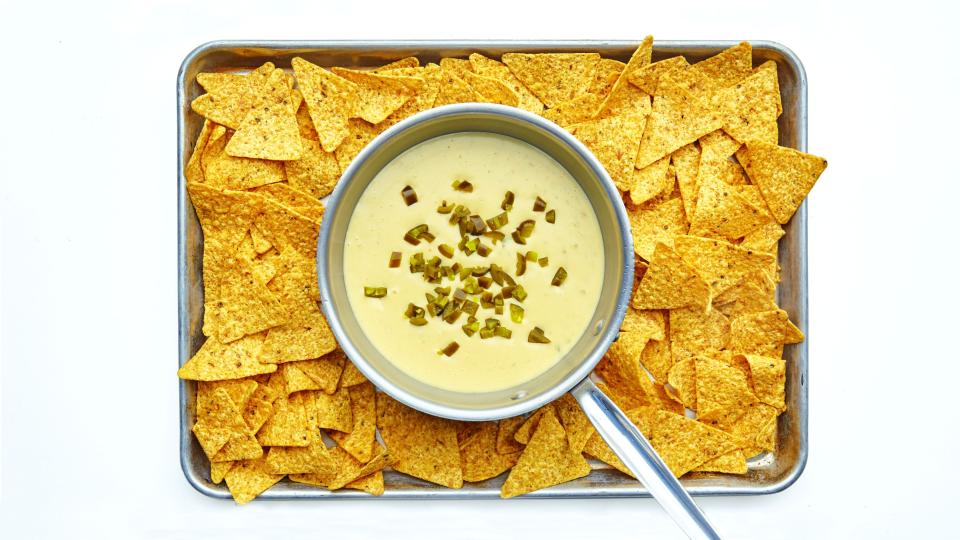

But that’s not all. In stir-fries, cornstarch helps thinly sliced protein like beef or pork brown evenly without overcooking, while simultaneously turning the liquidy soy, rice wine vinegar, and mirin into a veg-coating sauce. Cornstarch creates gravy that pools in, rather than drips down, mashed potatoes; it binds together runny fruit fillings into juicy-but-sliceable pie slices; it gives otherwise thin soups body (like a hair volumizer for your broth!); and it is the magical thickener in Sohla El-Waylly’s spicy, creamy queso.

But with all of this power comes great responsibility. To harness the incredible thickening magic of cornstarch for soups, dips, and custards/puddings/ice creams (that is, wherever there’s a large amount of liquid involved, more so than in a stir-fry or pie filling), you can’t just throw it in the pot and hope for the best. No, you have to treat it right—specifically, in these two ways.

First, you’ve got to make a slurry.

It sounds like an unfortunate weather forecast (slush plus flurries?), but a slurry actually refers to a mixture of cornstarch whisked with a small amount of cold or room temperature liquid. In the queso example, the slurry consists of cornstarch plus ¼ cup milk. Making a slurry adds another step to the recipe, sure, but it also reduces the risk that the cornstarch will clump up into starchy, grainy pockets when added to the rest of the liquid. It’s worth it.

Second, you must fully activate the power of the cornstarch by bringing the mixture to a boil.

While whisking or stirring constantly (again, lump prevention), pour your slurry into the pot of warm liquid. Continue to cook, stirring constantly, until the mixture has come to a boil and thickened, usually 1 to 2 minutes. Cornstarch needs heat (in the ballpark of 203°F) in order for “starch gelatinization”—that is, the scientific process in which starch granules swell and absorb water—to occur. In other words, if you don’t heat your cornstarch to a high enough temperature, your mixture will never thicken. But once your liquid has boiled, lower the heat and don’t return it to a simmer—you’ll risk destroying the starch molecules and ending up with a thin mixture yet again. (In that unfortunate event, make another cornstarch slurry and try again.)

If all of this seems a little fussy, just think: Cornstarch does so much for us, why not commit to doing these two acts in return? Your queso deserves it.

Get the recipe:

Queso, Not From a Jar

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit