For dancers, coronavirus wipes out stage, TV and video work. Life is 'grief and fear'

Choreographer and image director JaQuel Knight was in the middle of preparing for the Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival — creating dances for three acts and hiring more than 75 dancers and 10 to 15 assistants across two weekends — when he learned that the event was postponed.

His work with Pharrell on the Something in the Water music festival was canceled and his TV deal and job on an artist's visual album fell through as productions, tours and events shut down to contain the coronavirus outbreak.

Knight, 30, took a financial hit, but as Beyoncé’s head choreographer — he created the iconic moves in “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” and co-choreographed Beychella — Knight knew he could weather the storm.

The dancers he hired, the ones who lived paycheck to paycheck and gig to gig, however, suddenly were out of work.

“At that moment, it became real to me. Many of those people are my good friends. [They] are going to be struggling with simple things like providing food on the table,” Knight said. “I started to think about how can I help the community, how can I help my friends, how can I be a soldier and a light of positive energy during a time that gets darker and darker every day it seems.”

It’s the new reality for L.A.'s commercial dance world, an already exclusive and fragile industry. As the entertainment business comes to a halt, commercial dancers and choreographers — the performers who animate film, TV and music videos — said the experience has been surreal and stressful.

“The air is thick with grief and fear, and you can feel that,” said Kathryn Burns, a choreographer who won an Emmy for her work on the series “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend.”

In his 20 years as a choreographer and creative director in film and TV, Lyrik Cruz never had a job completely canceled. But on March 13, after he finished a two-month tour and prepared to head to Chicago for a Netflix pilot, the cancellations began rolling in.

“I didn't even want to open my emails anymore because it was just like a slew of cancellations back to back,” Cruz said. “We're choreographers and dancers for hire. Not many of us are working jobs where we get a salary, or where we get sick-pay days; that’s just not the way it works for our industry.”

Choreographer and dancer Kiira Harper, who has performed with Janelle Monáe and Beyoncé and has served as an assistant choreographer for Lizzo, put it another way: "We're all broke."

Pay for commercial dancers varies wildly. Dancers Alliance, a group that negotiates equitable rates and working conditions for nonunion workers, sets a minimum of $250 for four to eight hours of rehearsal and $500 for dancing in a live show or non-union music video. Dancers often supplement their income by teaching classes, and a gig at a popular L.A. studio can bring in a couple of hundred dollars. During the coronavirus quarantine, both types of work have dried up.

At 30, Harper said she had finally been at a point in her career where she could begin saving money. Before the wave of cancellations, she was booked through June to teach dance classes, shoot a music video in Cuba and work in artist development for music labels including Atlantic Records.

She recently received notification that one dance studio where she teaches regularly is unable to pay her for March classes.

“To be honest, I flew cross-country,” Harper said. “I'm in New York with my parents right now so I don't have to spend money on groceries and driving my car and doing all that other stuff.”

Clear Talent Group, an agency that helps dancers and choreographers navigate the business side of the industry, said the No. 1 question it has received in the last few weeks is, “How am I going to pay rent?” agent Matthew Logsdon said.

Most L.A. dancers are self-employed and need multiple streams of income to make ends meet.

“Beyond making dances, they're also teaching or they're in the health and wellness lifestyle industry, whether it's Pilates or yoga teacher,” said Raélle Dorfan, executive director of the Dance Resource Center. “Basically every line of income has been shut down.”

The Dance Resource Center opened applications for its emergency fund, which will provide up to $500 for L.A. dancers and companies, and in five days the group received about 150 applications. "We hope to distribute funds to as many applicants as possible, thus the amounts will likely be less so we can serve more," Dorfan said.

Some dancers said they would like to see more financial assistance, such as a relief fund, from the giants of the entertainment business.

“So many of us have worked with so many celebrities and so many big production companies,” Cruz said. “Dancers are always at the bottom of the totem pole, have always been. Not one celebrity that we've worked with or anything has reached out to any of us.”

Harper mentioned others who work behind the scenes — camera operators, stage hands, directors, lighting teams — to help big stars bring their visions to life.

“We’re all out of work; it's not just the dancers,” Harper said. “We're all indefinitely frozen. It’s kind of like a purgatory.”

Although the upcoming months are uncertain, the dance community is resilient, Dorfan said.

“Dance is chronically underfunded as it is. And so I think dance-makers have been making and presenting work in innovative ways here in L.A. for years. So they're adapting to this new normal.”

For the dance community, that means connecting online and finding new ways to generate income.

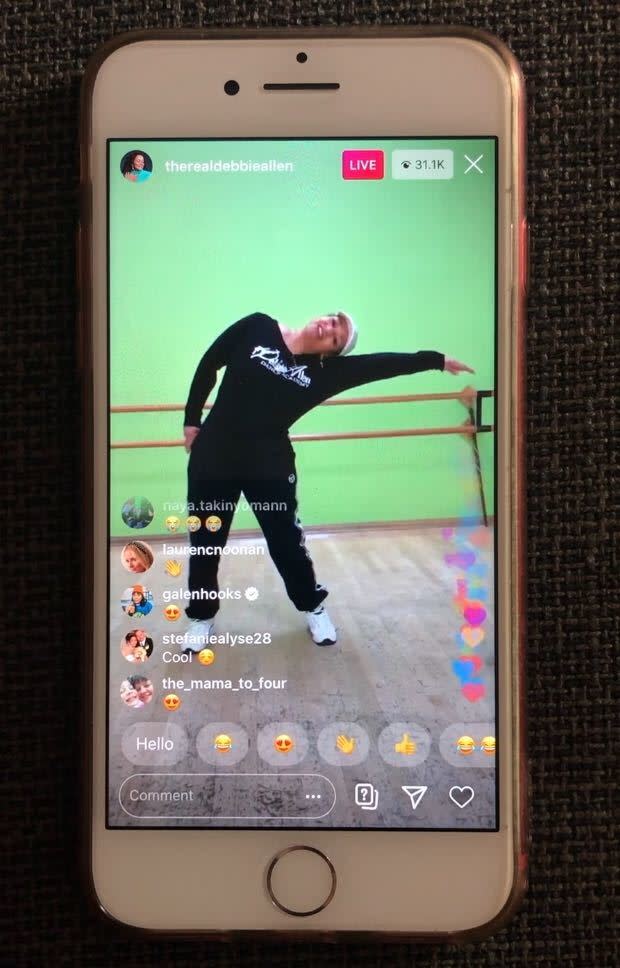

Like many choreographers, Cruz, Harper and Knight have begun teaching classes on Instagram Live.

Cruz said teaching his Latin fusion class online offers a way to “share a little bit of happiness and positivity,” he said. “Sometimes we forget the power of social media. And as much as people frown upon it sometimes, it really keeps a lot of us connected.”

Cisco Ruelas, a choreographer who has worked with Lil Wayne and Jennifer Lopez, estimated that 80% of his income comes from teaching classes. Ruelas’ largest in-person classes held about 180 students.

A recent Instagram class attracted about 5,000 people. Although the class was free, Ruelas received donations over Venmo, which might be his only source of income in the immediate future.

“I didn't want no one to feel guilty for taking class, so that's why I didn't put a number on it,” Ruelas said. “But some people donated $40, which my class only costs $15 in person. Some people donated $5.”

To give back to the dance community, Knight organized an in-person meal giveaway in collaboration with restaurant Everytable, handing out 2,500 healthy meals in the Burbank studio KreativMndz Dance Academy. Others in entertainment, including singers, stylists and makeup artists, were also invited.

Knight plans to continue meal giveaways in other cities and will launch a fundraiser for the dance community, “helping those people stay on their feet, keeping people positive,” he said. He knows about the challenges facing dancers and choreographers working to establish footing in the industry.

“When I first started, we were sharing rooms; it was five of us in the apartment,” Knight said.

Reflecting on how such a pandemic might have impacted him about 10 years ago at the beginning of his career: “I probably would be on a flight back to Atlanta now, figuring out how to get out of my lease and get back home."

Working behind the most popular artists in the world may seem like easy fun and glamour, Knight said. “The real life of it is hard.”