Delta Buckles Up For Turbulence

IT’S SHOWTIME at Salt Lake City’s Grand America Hotel. As the bouncy groove of “Feel It Still” by the band Portugal. The Man pulsates through the cavernous ballroom, some 200 Delta Air Lines employees wait their turn for a selfie with CEO Ed Bastian. Sporting a slim-tailored suit, black designer tennis shoes, and tortoise-shell glasses, the 6-foot-2, silver-haired Bastian poses with an arm thrown over the shoulder of a burly baggage handler, then trades grins with a duo of flight attendants clad in newly issued uniforms whose deep purple hue their designer, Zac Posen, dubs “Passport Plum.” The fans relay their cell phones in a constant stream to a Bastian aide who clicks away so that everybody gets a souvenir.

Bastian reputedly never leaves a selfie session until the procession is finished, and today, the parade lasts over an hour. “We meet celebrities all the time, and I’m never starstruck,” says flight attendant Danielle Strickland, 31. “But this was the first time I got a picture with Ed Bastian, and I was starstruck.”

The occasion is a “Velvet” (for “velvet rope”), a conclave Bastian created in the dark days when Delta was mired in bankruptcy. He now holds Velvets once a month in one of the airline’s hub cities. Bastian headlines each extravaganza with an early morning pep talk, followed by the photo op. Then he embarks on meet-and-greets with local employees that proceed at the frenzied pace of a political campaign. This Tuesday in September is no exception, with the CEO delivering speeches to reservation agents at a regional call center and then to ground workers at Salt Lake City International Airport; touring the construction site of Delta’s new $3.5 billion terminal there; and strolling into the pilots’ break room to chat up blasé-looking captains. Bastian—trailed by a video cameraman—finds time at each stop to answer questions, fodder for spots on the “Ask Ed Anything” internal video site that channels his message to employees.

To veteran airline-watchers, Bastian’s knack for courting employees calls to mind two past industry leaders famous for rallying the troops: former Continental CEO Gordon Bethune and Southwest cofounder Herb Kelleher. But while those chieftains were folksy, flamboyant, and even profane, Bastian’s style is different. If Bethune and Kelleher were brass bands, Bastian’s a smooth jazz ensemble. Through the headlong rush, he comes off as coolly relaxed. His talks, delivered sans notes, flow in paragraphs uninterrupted by the usual “you knows” and “I means.”

Most of all, Bastian hits notes that get big reactions. At the Salt Lake City Velvet, he tugged at veteran workers’ heartstrings: “Look where we’ve come from! Through bankruptcy, the Northwest merger, fuel going up and down. We didn’t have much, but we had each other!” Minutes later, it was all about pay. “We’ll deliver over $1 billion to you in profit sharing on Valentine’s Day for the fifth year in a row.” Next up, the Big Vision: “We’re king of the U.S., the undisputed national champion,” he declared. “But our future is global. The world is the Olympics.”

Rah-rah hyperbole sounds comfortable in Bastian’s baritone. He seems to know the cheerleader role fits him like his designer sneakers. But he may soon find himself working harder than ever to rally the troops. Rough air looms for Delta, in the form of shrinking profits and a slowing economy. And if the company doesn’t execute its strategy to near-perfection, all of its stakeholders—from wheelchair-pushing porters to billionaire institutional investors—are going to need a lot more cheering up.

The worker harmony that Bastian does so much to promote is a major reason Delta is the best-run, most profitable carrier among the Big Three U.S. global airlines, a group that includes American and United Continental. This year, Delta’s on-time arrival record of 85% is tops among the giants, waxing United and American (both 80%) while also besting Southwest, the biggest domestic budget carrier (79%). For every mile it flies one seat in the U.S., Delta collects 19% more in revenues, on average, than its rivals.

The reasons for that rich premium are twofold. The first is the industry’s strongest airport network. Delta commands more fortress hubs—Atlanta, Minneapolis, Detroit, and Salt Lake City among them—than any other airline, which means it has more routes on which it faces less competition, including from low-cost carriers. Overall, Delta has also been the most aggressive in adding flights to big coastal cities like New York, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle, where the battle for business customers is fierce. That battle is a showcase for Delta’s second advantage: Its superior reliability and onboard service, which tilt corporate business toward the carrier, bringing the airline a more lucrative and profitable mix of traffic. “Delta’s investment in service and operating performance means that at the same price, companies will lean toward choosing Delta,” says Olivier Benoit, VP of the global air practice at Advito, a firm that manages travel programs for large companies.

But despite all those advantages, the smooth ascent that Bastian promises in Salt Lake City will prove difficult to achieve. It’s a gauge of how tough the business has become that the best of the Big Three will need brilliant navigation to keep thriving. Put simply, Delta’s profits have been heading in the wrong direction, falling sharply from the peaks of 2015 and 2016. And the same strategic moves that have burnished the airline’s image with employees and consumers—big investments in worker compensation and equipment upgrades—are now among the factors weakening its profitability. While rising fuel prices are a factor, Delta’s non-fuel expenses, led by labor, have been rising rapidly for the past four years, far outpacing revenues. (See chart above.) This year has been no exception: Boston research firm Trefis stated in a recent report that “Heavy costs are hurting margins” at Delta; Trefis projects that Delta’s cash flows will decline by 11% by 2022.

As investors fret over these numbers, Delta’s stock has lagged the market. Since the beginning of 2017, it has risen 15% vs. 25% for the S&P 500. The best measure for how investors assess its prospects is its trailing price-to-earnings multiple: Delta’s P/E stands at just 10.1, well below the S&P’s 21.1 and almost identical to those of American and United. Those puny P/Es signal that individuals and institutions voting with their dollars view America’s global airlines as lumbering legacies whose earnings will decline steadily in the years ahead.

Costs are hardly the only factor narrowing Delta’s margin for error. A recession, or even a more modest slowdown, could reverse a recent resurgence in fares and revenues. Europe has become Delta’s fastest-growing market, but turbulence from Brexit could halt the upswing. And heavy competition in the credit card market could drain the little-noticed but deep pool of profits that Delta shares with American Express through its SkyMiles credit card.

Given the cloudy outlook, taking Delta to new heights will require brilliant piloting. And Bastian, 61, a former CFO and crack numbers man who took the corporate captain’s seat in mid-2016, knows it. His plan rests on two legs: holding costs to a more manageable rate and expanding revenues faster—chiefly by expanding where the big growth is, in international markets, and continuing to exploit that underappreciated credit card partnership.

In a wood-paneled office once occupied by Delta’s principal founder, C.E. Woolman, in a quaint, two-story brick building resembling an oversize cottage on Delta’s Atlanta campus, Bastian explains his blueprint. “In the past couple of years, we had a lot of cost inflation … in part because we still needed to catch up on labor from the big cuts following our bankruptcy,” he says. “But now we’re caught up.”

The U.S., he continues, is a mature airline market today, so “in the long-term, we want to lift our international revenues from around 35% of the total to 50%.” Will that strategy lift Delta’s operating margins back to their 16% peak of 2015 and 2016? “That was a sweet spot because oil prices had dropped, but business fares were still high,” he explains. He projects confidence, but when pressed for specific targets, he gets a little more reticent, admitting, “This business is humbling.”

THOUGH BASTIAN has been CEO for only 2½ years, he’s already helped steer Delta through two decades of turbulence.

The oldest of nine children, Bastian grew up in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. His father was a dentist who worked from a home office; Bastian’s mother served as the dental assistant. His family’s idea of luxury travel involved cramming everyone into a station wagon and driving to Florida for a winter vacation; Bastian didn’t board a plane for the first time until he was 25.

By then, he had already made a name for himself in accounting. Shortly after joining Price Waterhouse just out of college as an auditor, Bastian discovered massive fraud at the ad giant J. Walter Thompson. During a 1981 annual review, Bastian found that the JWT business that syndicated TV shows and sold spots on those shows to advertisers had booked $50 million in phony revenues. The scandal prompted an SEC investigation and damaged the careers of several Price Waterhouse partners, but it boosted Bastian’s stock: He made partner at age 31. One of his perks was supervising voting for the MTV Video Music Awards, where Bastian would appear onstage in a tux to hand ballots to rock-star presenters. One year, Bastian recalls, punk rocker Billy Idol took his ballot and stuck it in his skintight pants, then pulled it out through his fly as the cameras rolled.

After an eight-year stint as a financial manager at PepsiCo’s Frito-Lay subsidiary, Bastian joined Delta in 1998 as controller. When soaring oil prices and competition from low-cost carriers hammered Delta in the early 2000s, the airline began slashing wages, at the same time that top executives granted themselves pension plans protected even in bankruptcy, along with “retention” bonuses. “The employees getting pay cuts saw their bosses getting bonuses for staying,” recalls Jerry Grinstein, who was a director at the time. Bastian quit in disgust in early 2004, joining a lighting and controls manufacturer in Atlanta as CFO. Six months later, Grinstein—who had been named CEO in a boardroom revolt—met with Bastian at a Starbucks and lured him back as Delta’s CFO, offering him the challenge of saving Delta for half the salary he was making at the lighting company.

Delta filed for bankruptcy in 2005, a gambit Bastian advocated as its only route to survival. It was during its Chapter 11 period that Bastian became the prime developer and champion of the comeback plan that defines the airline’s strategy to this day. To sell the blueprint to employees, Bastian in 2006 headlined the first Velvets at a shuttered Macy’s in downtown Atlanta. His pitch: Delta would rebound as an upscale carrier that distinguished itself via superior reliability and customer service, commanding premium prices. He pledged to restore base pay to competitive levels and unveiled a profit-sharing formula that’s still in place today: If Delta thrived, employees would share richly in the upside. Although Delta was losing billions of dollars a year at the time, workers rallied behind Bastian’s vision. The workforce also found common cause in successfully fighting a 2006 hostile takeover bid from U.S. Airways, brandishing the slogan “Keep Delta My Delta!”

Bastian led the often-acrimonious, 18-month negotiations with creditors that enabled Delta’s emergence from bankruptcy in April 2007. According to associates, his stamina was extraordinary, and so were his demands. “I’ve never been driven harder in my life,” recalls Marshall Huebner, a Davis Polk law firm partner who worked closely with Bastian. “I had lash marks on my back. Then, when it’s over, he wrote me a two-page letter, in fountain pen, about how he couldn’t have done it without me.”

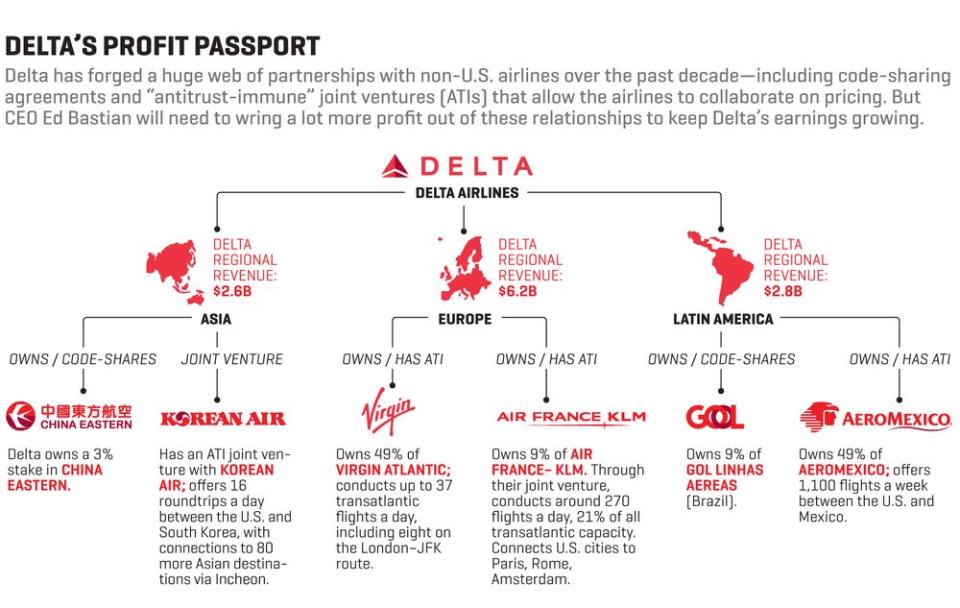

His next job was managing a process that often spells disaster: merging two airlines. In 2008, Delta acquired Northwest just after it emerged from bankruptcy, and for the next two years, Bastian smoothly combined fleets and workforces, orchestrating what’s generally regarded as the best major marriage in airline history. When Richard Anderson, who’d served as Northwest’s chief in more prosperous days, became Delta’s CEO in 2007, he promoted Bastian to president, and the two served together for the next 8½ years. Anderson was a hawk on operations, managing the fleet, upgrading airports, and improving in-house maintenance. Bastian was the dealmaker, building the industry’s largest portfolio of partnerships with foreign carriers. That web now includes investments in Virgin Atlantic, AeroMexico, GOL of Brazil, and China Eastern, and a joint venture with Korean Air—partnerships crucial to his strategy today.

Bastian was widely recognized at Delta as Anderson’s heir apparent, and the handoff of the CEO role, in May 2016, was seamless. But he became a nationally known figure thanks to an unanticipated conflict: a high-profile duel with the National Rifle Association. This March, following the mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., Bastian got emails from Parkland students drawing his attention to the discounts Delta offered to NRA members on flights to its annual convention. Bastian had already been appalled when an NRA spokesperson declared, in response to criticism of the organization’s advocacy, that “Many in the legacy media love mass shootings” and that “Crying white mothers are ratings gold.” In reaction to that kind of rhetoric, Delta canceled the discount.

Even though only 13 members had ever used the discount, the NRA vociferously complained. If the airline didn’t reinstate the deal, the Georgia state senate threatened to block passage of a fuel tax exemption that would have saved Delta $40 million a year. Bastian refused, and the tax break was killed. But his stance generated a publicity coup for Delta. The CEO issued a widely reported memo to employees stating,“Our values are not for sale” and deftly defended the airline in a range of public appearances. Delta’s stance, Bastian tells Fortune, wasn’t designed to burnish the airline’s brand, but it brought precisely that benefit: “We won a lot of fans.”

One partner who lauded Bastian’s stance was Sir Richard Branson, founder and president of Virgin Atlantic. “I couldn’t agree with him more,” Branson says. “Business leaders can’t leave it up to the politicians.” When such weighty issues aren’t in play, the two leaders share a lighter rapport, especially at joint appearances—frequent events since 2013, when Delta bought a 49% stake in Virgin Atlantic. At a recent fundraiser in Atlanta, Branson produced a pair of scissors and cut off Bastian’s tie. (“He should wear an open shirt, like me,” says Branson.) Branson covets Bastian’s footwear as much as he detests his neckwear. When they appeared onstage recently at Delta headquarters, Branson kneeled down and removed Bastian’s $1,500 Berluti sneakers (a gift from Bastian’s girlfriend), then slipped them on. “I stole them, and he’s not getting them back,” said Branson in a recent interview. “I’m wearing them as we speak.”

THE U.S. AIRLINE INDUSTRY is in far better shape than it was when Bastian first started rallying his rank and file. But no airline has changed more than Delta. As its free cash flow swelled, an airline that once mainly flew old planes to aging terminals has invested heavily in new aircraft. It’s spending billions of dollars a year at its hub airports, building and refurbishing terminals and concourses. In 2018, Delta will lay out $5 billion in capital expenditures, more than double the number four years ago; its airport projects in Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, and Salt Lake City alone will cost $8 billion over the next several years. Since the third quarter of 2015, according to ISS Corporate Solutions (ICS), the total stock of capital Delta deploys has increased by 12% to $51.2 billion.

Delta needs to generate strong returns on those extra billions in fresh investments. But doing so is far from a sure thing. One yardstick for such performance is economic value added, or EVA, a metric that measures “economic profit,” the amount companies earn over and above their cost of capital. According to ICS, for the 12 months ending Sept. 30, 2016, Delta exceeded its 6.5% cost of capital by 5.8 percentage points. But over the past 12 months, its margin has fallen to 0.3%. That’s still respectable, a bit like shooting par for a pro golfer. “Delta is delivering slightly better returns on capital than what investors would expect from holdings that are equally risky,” says Mark Brockway, managing director of ICS. But it’s not the kind of number that convinces investors that Delta has “operating leverage”—the capacity to lift margins enough to send its profits skyward.

Delta’s dilemma is the product of trends that were years in the making. So far in 2018, revenues are growing at a brisk 8%, and analysts expect the airline to bring in a record $44 billion, thanks to a strong economy and a rebound in business fares. But over the previous four years, sales barely budged, so all told, they’ve grown a total of only 10% since 2014. By contrast, labor costs exploded over that period, from $8.1 billion to around $11 billion, a rise of 36%. As a result, Delta is expected to post pretax profits this year of around $5 billion—notably lower than the $5.9 billion it reported in 2015.

Why did revenues go flat? The primary driver was a spate of fare wars that hammered Delta’s most lucrative market, premium business fares. “From 2011 to 2014, the supply of seats grew more slowly than demand because of high fuel prices, and low margins discouraged airlines from adding seats and flights,” explains Savanthi Syth, an analyst with Raymond James. But when oil prices collapsed in 2015, low-cost carriers, led by JetBlue, Southwest, Spirit, and Frontier, began invading the Big Three’s turf with a flood of new flights. Capacity, the total number of “seat miles” flown on domestic carriers, jumped between 4.5% and 5.0% annually in 2015 and 2016.

To fill the growing sea of seats, the budget airlines offered super-low fares to customers who booked their tickets within a few days of departure. These “walk-up” travelers include business folks who aren’t bound to specific airlines by corporate contracts and are free to choose among competing carriers. This “unmanaged” segment accounts for 15% of all Delta travelers and 35% of total fares. American and United, in particular, didn’t want to risk losing these customers. So starting in mid-2015, they matched the low-carriers’ walk-up fares with their own cut-rate deals.

The wave rippled across every business market. JetBlue, for example, expanded in New York’s JFK and in Boston, two big markets for Delta, offering its Mint premium class on long-haul routes. “Walk-up fares were crushed,” recalls Bastian. He estimates that the price of business tickets, across the entire industry, dropped as much as 25% between 2014 and the start of 2018.

Those trends are now moving in the other direction. A jump in jet-fuel prices—from as low as $40 a barrel in early 2016 to $90 today—has increased costs-per-seat at the budget carriers far more than for the Big Three, forcing their fares higher. Bastian says that business fares are no longer unhinged from costs and are tracking oil prices with around a six-month lag. So far, he says, Delta has recouped around 50% of the drop in business fares, and at $90, he adds, “the budget airlines are cutting back on the same routes.”

Still, competition on fares is far from Bastian’s only challenge: The airline’s ballooning compensation levels have posed an unruly problem of their own. Delta has an extremely generous profit-sharing plan. Each year, on Valentine’s Day, Delta hands its workers 10% of its first $2.5 billion in pretax profits, and 20% on any profits above that level. Those bonuses are the main reason its employees earn, on average, 5% more each year than their counterparts at United or American.

Management had intended to make the deal a bit less sweet. In 2015, Delta agreed to raise base pay the following year by 18.5% for its 50,000 flight attendants, mechanics, and other frontline workers, all of whom are nonunion, in exchange for the workforce accepting a smaller share of profits. Those workers liked the tradeoff. But later that year, Delta’s unionized pilots rejected the deal. Then in 2017, flush with profits from a drop in fuel prices, Delta granted all of its workers another 6% increase. And finally, this year, Delta decided that rather than keep two separate plans, it would restore the 10-and-20 formula for all workers. The bottom line: All told, base pay waxed around 25% in little over a year—and all workers still have the old profit-sharing plan that management had tried to cap.

Bastian pledges to keep Delta’s employees the best paid in the industry. But he says that looking forward, pay raises should pretty much match U.S. economic growth including inflation, today around 4.5%, plus profit sharing. (If this move proves unpopular, he’ll presumably hear about it in the selfie lines.)

Meanwhile, the CEO plans to reap more savings through a strategy called “up gauging.” That process involves replacing older, smaller planes with bigger, more fuel-efficient aircraft on longer routes as well as in its fleet of smaller, regional jets. Delta will have retired 30% of the “mainline” planes flown on its major routes by 2020. Today, it flies around 300 two-decades-old, fuel-guzzling MD-88s and MD-90s that carry 149 and 158 seats, respectively. To replace them, Delta has ordered fleets of the A321 and A321neo from Airbus, and 737-900s from Boeing, which hold between 180 and 197 seats. Once that’s done, for a large portion of its fleet, Delta will be able to fly 25% more customers on the same number of flights. What’s more, despite being larger, the new aircraft consume around 20% less fuel than the MDs and don’t require larger crews. Delta will be able to put a lot more passengers on those planes at the same or lower fixed costs.

IN THE QUEST FOR MORE REVENUE, Delta has a very profitable ace up its sleeve—or, more accurately, in millions of people’s wallets. It’s a major marketing partnership that’s immune to the cycles in fares and fuel costs that roil financial results for airlines in general, and it’s one that Bastian can take credit for, having negotiated it back when he was CFO and president.

Each year, consumers spend $80 billion on purchases through cobranded American Express–Delta SkyMiles credit cards. AmEx buys miles from Delta that Delta exchanges as rewards for spending on that card, as well as through rewards programs on other AmEx cards. In the past, AmEx and other credit card companies had all the leverage in these relationships, buying big chunks of miles on the cheap when carriers were desperate for cash. But today, Delta’s fortunes, and its brand, have greatly improved, and it’s the airline that has the leverage. “It’s a revolutionary change, a stabilizing force,” says Delta CFO Paul Jacobson. “It’s loyalty to Delta that brings loyalty to the SkyMiles card.”

The result: This year, AmEx will send Delta $3.4 billion in revenues from two sources. The first is the purchase of miles. The second is a large chunk of the “merchant fee,” the approximately 2.5% that AmEx collects from retailers of the value of each purchase customers charge to the card. AmEx makes its money on revolving credit interest and annual fees—but Delta now gets most of the merchant fee. Joe DeNardi, an analyst for Stifel, estimates that Delta is reaping 66% margins from the AmEx deal. Bastian says that estimate is “much too high” but acknowledges that margins are “extremely healthy.” Whatever the actual margins, they’re higher than on core airline operations and growing at over 11% a year on that $3.4 billion base.

“We’ve had a lot of cost inflation because we needed to catch up on labor after the big cuts from our bankruptcy. Now we’re caught up.'”

Ed Bastian, CEO of Delta Air Lines

Nonetheless, that big flow of profits is vulnerable. “I argue that the margins will fall for two reasons,” says Gary Leff, who writes the traveler-oriented blog View from the Wing. “The interchange will be driven down, either by competition or regulation. And airline cards are getting tremendous competition from bank cards” with comparably high rewards. In a best-case scenario, Leff and others predict, the SkyMiles deal will help support Delta’s bottom line for a while as Bastian and his team figure out how to sustain higher revenues in the core airline franchise.

To make that growth happen, Delta is looking overseas—where growing middle-class populations and booming business climates are generating the kind of growth in demand that’s a thing of the past in the States. And here, Delta may have a decisive edge. “Delta’s developed far more big investments in foreign carriers and formed more overseas joint ventures than any other U.S. airline,” says Andrew Davis, a portfolio manager for T. Rowe Price whose funds hold $700 million in Delta shares. “As its global footprint expands, Delta can definitely generate the revenue growth it needs.”

Traffic between the U.S. and Europe is Delta’s fastest-growing franchise, posting a 12% jump in revenues so far this year to an annualized $6.2 billion—led by a 15% increase in the U.S.-to-U.K. segment. Earlier this decade, Delta was a laggard on what’s by far the premier route for business travelers between the U.S. and Europe: New York City to London’s Heathrow Airport. But the 2013 launch of Delta’s partnership with Virgin Atlantic, in a single stroke, made it a major force in that market and especially to Heathrow. “What’s known as NYLON put Delta on the map with the big banks in New York and London,” says Joe Brancatelli, who runs the website JoeSentMe.com for business airline travelers.

Today, the Delta-Virgin alliance is second only to the American–British Airways joint venture on the NYLON route, offering seven or eight flights a day. Profits are lively for global U.S. banks, and consultants and dealmakers are shuttling back and forth to London to advise on how best to handle Brexit. The strong dollar is making Europe in general a bargain for U.S. leisure travelers, and on the U.K. side, Delta-Virgin offers frequent flights to several of the Brits’ favorite vacation haunts, among them Orlando and Las Vegas.

Delta also has a partnership with Air France–KLM to serve European cities. That’s lucrative, too, giving Delta a share of income on routes to cities such as Paris and Amsterdam, and connections to other cities within Europe from those hubs. All of these relationships are “antitrust-immune,” which means that Delta and its partners can cooperate to set fares and schedules.

Even though revenue has been growing rapidly, Delta has room for improvement. For a traveler from the U.S., Delta, Air France, and Virgin Atlantic can act as a single partnership. It can offer a New York bank, for example, a package deal that includes all those Virgin flights to Heathrow, as well as Air France–KLM’s transatlantic service and its vast network throughout Europe. But on the European side, the Delta–Air France and Delta-Virgin partnerships are considered independent of each other. That means European corporations can’t get comparably seamless business-travel arrangements for their employees unless they sign separate deals with the two joint ventures, something many aren’t willing to do.

Delta’s solution: Merge them. The two joint ventures have applied for permission to merge from the U.S. and EU, and Bastian is confident approval will arrive shortly. When they get a yes, they’ll be able to offer a wider array of bookings, and profits will follow. “Combining the two JVs would be a big deal,” says Peter Vlitas, SVP of airline relations at Travel Leaders Group, a firm that helps corporations negotiate travel contracts. “The combined alliances would offer full global corporate travel packages to companies based in Europe.”

IN THE MEANTIME, Bastian aims to reverse a long retreat for Delta in the Pacific—and he’s doing so with one of his most audacious gambits as CEO.

Between 2012 and 2017, Delta’s revenues from Asia fell 35%, from $3.6 billion to $2.3 billion. Until recently, Delta served Asia mainly through a hub at Narita International Airport in Tokyo, connecting traffic from there throughout Asia on its own planes. But in 2013, the Japanese government transformed Haneda, an airport much closer to Tokyo, from a domestic to an international hub. The result was that many of Delta’s “destination” travelers to Tokyo—passengers who planned to end their trips there rather than pass through—chose other airlines, making its Narita service less financially viable. American and United suffered less, since they have partnerships with Japanese airlines to help them operate in both Narita and Haneda. But Delta didn’t have a Japanese partner. (Bastian courted JAL, without results.)

Last year, however, Delta signed a new, antitrust-immune joint venture with Korean Air for service to giant Incheon International, near Seoul. That hub, which Delta president Glen Hauenstein calls “the Taj Mahal of world airports,” opened in 2001 and is one of the world’s newest and biggest facilities. From Narita, Delta flew to 25 cities. From Incheon, it will operate 45 gates at ultramodern Terminal 2, which made its debut in January 2018 in time for the Pyeongchang Winter Olympics. From there it will connect on Korean Air planes to 80 destinations, including 40 in China. “Lots of airlines fly nonstop to major cities like Shanghai or Seoul,” says Leff, of View from the Wing. “The game changer is that Delta can now reach dozens upon dozens of secondary cities throughout Asia, whether it’s Hanoi or Harbin.”

A nonstop flight from JFK to Incheon stretches some 7,000 miles. This fall, Bastian was contemplating a shorter if no less daunting distance: 26.2 miles. Bastian, a regular jogger, had pledged to run in the New York Marathon in early November to support Atlanta’s Rally Foundation, a charity for childhood cancer research. His biggest obstacle: a torn meniscus that had him hobbling in late October. Come race day, Bastian went the distance, albeit in a time of more than six hours. “On mile 15, my calves knotted,” he says. It “turned the last 10 miles into a true battle.” The experience may prove to be prophetic: There’s likely to be some pain for Bastian before Delta’s next big gain.

A version of this article appears in the December 1, 2018 issue of Fortune with the headline “Soar While You’re Ahead.”