ETF Premiums: No Worry—Until They Bite

Headlines today focused on big outflows from the iShares iBoxx High Yield Bond ETF (HYG). But the real story was the object lesson on how terrible ETF trading can cost you big, big money.

It’s axiomatic in ETFs that everyone wants a fair deal. It’s axiomatic in life really. Nobody ever wants to pay too much when they’re buying something, or get too little when they’re selling.

With most ETFs, this is never an issue. A fund like the SPDR S'P 500 ETF (SPY) trades within a penny of the fair value of its underlying stocks—day in; day out; all day; every day.

The reason this is so is because of the creation/redemption process. If investors buy a lot of SPY, driving the price up over its fair value, authorized participants swoop in and arbitrage-out the price difference, creating new shares of SPY to sell, while buying up the underlying stocks of the S'P 500 Index. This helps depress SPY’s price while simultaneously supporting the prices of the underlying stocks.

And because it works so well so much of the time, I generally tell folks not to stress too much about premiums and discounts. But there are two cases where you can learn a lot—and potentially save some money—by paying attention.

First, let’s take the case of international funds. Most international ETFs will show a measurable premium or discount on any given day because they trade while their underlying securities are done changing hands for the day.

That means the net asset value (NAV) is “stale” at 4 p.m., while the market price is “live.” Such is the case with iShares’ popular EAFE ETF, the iShares MSCI EAFE Index Fund (EFA).

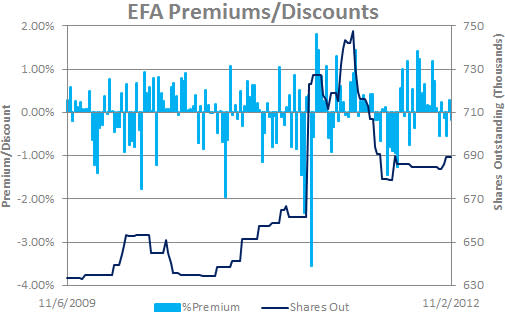

You can see here that for most of the 2009-2010 period, the fund traded at mean-reverting—effectively random—premiums and discounts.

But note the big discount-to-premium swing in November 2011. That corresponds to the blue line on the chart, which maps shares outstanding.

Changes in shares outstanding mean one of two things—either APs are responding to premiums and discounts, or large investors are buying big, negotiated blocks of shares.

In this case, my suspicion is the latter—a large investor came in and bought a huge chunk of EFA, effectively adding to inventory. In response, for a period of a few days, there was a perception of a “glut” of EFA shares; in effect, causing the short-term discount. That discount then evaporated with the resumption of normal trading.

In general, however, I discourage folks from speculating too much on single-day reports of creations and redemptions—the data are noisy, and are often corrected after the fact. And of course, it’s impossible to know whether creations are proactive—an ETF investor calls an AP and asks for 200,000 shares for a major position, at a negotiated price; or reactive—an AP sees an arbitrage opportunity and jumps.

With that in mind, let’s compare what happened with EFA to another fund tracking the exact same index, the Vanguard MSCI EAFE ETF (VEA).

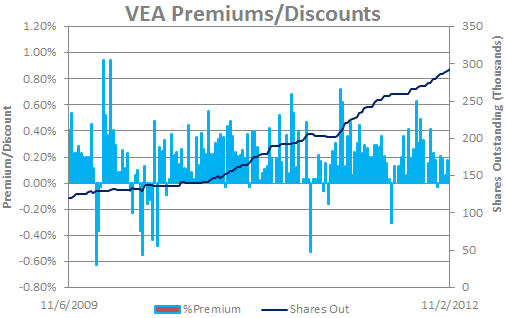

Two things are going on in this ETF that make it vastly different than its kissing cousin, EFA.

The first is that Vanguard “fair-values” its NAV at the end of the day. That means that instead of relying on the closing price of Toyota Motor Corp in Japan, Vanguard revalues the stock based on how proxies—futures and American depositary receipts—have traded during the U.S. trading session. This serves to remove most of the noise from the chart. Gone is the random mean reversion.

What then explains the slight, but persistent, premium here? The blue line again represents shares outstanding. For most of this three-year period, VEA has been steadily gaining assets. In periods of slight decline or flat growth like in the fall of 2011, the premium disappears or swings to discounts.

But in general, this is the story of slow, steady buying pressure keeping the price of the ETF in the open market just a bit above fair value. And, as long as this kind of premium persists, the changes are reasonable, so you shouldn’t care too much. Someone in this period most likely bought when the fund was at a premium of 20 basis points or so, and would probably have sold at a similar level.

But “probably” can really bite you in the you-know-what, as investors in the iShares iBoxx High Yield Bond Fund ETF might have discovered in the last few days.

HYG invests in high-yield U.S. corporate bonds. And while it invests generally in the more liquid part of that market, we’d expect it to trade at a consistent premium for one simple reason:Bonds are valued at the bid price for fund accounting purposes.

So the NAV is always at the “What would it cost to dump the portfolio?” price, while the market recognizes that that mechanism probably understates the true value of the portfolio. Therefore, it’s willing to pay up a bit.

Because the market for junk bonds is less efficient than that of, say, global industrial equities, any junk bond fund will also be more sensitive to swings in demand. Looking at HYG, you can see this throughout the first half of the past 12 months.

Strong demand for the fund—shown by increasing shares outstanding—kept premiums over 1 percent, spiking as high as 2.63 percent on Dec. 27, 2011. By the way, historically, it traded even higher, at more than 3 percent.

With today’s headlines about investors leaving junk bonds—and indeed, the $219 million in net outflows flows yesterday were quite large—some investors might be deciding it’s time to book their gains for the year.

But doing so would leave substantial money on the table. If you were the investor unlucky enough to have bought in December and sell today, you will in fact be booking over 3 percent in negative returns on your position, solely because of the sensitivity of HYG to net flows.

To be fair, you’re still up on your position—more than 8 percent since Dec. 27, in fact. But your returns weren’t “fair,” in that you overpaid to get in, and you got hosed on the way out.

How do investors solve this? Simple.

Look at the premium/discount pattern for a fund before you buy it, and avoid buying at above-normal premiums. Similarly, unless you have some reason to believe your position is tanking and you simply have to be out now, wait for discounts to resolve before you press the “Eject” button on your position.

And lastly, always dig under the hood to understand why a fund might be trading away from fair value.

There’s almost always something to learned in finding the answer.

At the time this article was written, the author had no positions in the securities mentioned. Contact Dave Nadig at dnadig@indexuniverse.com.

Permalink | ' Copyright 2012 IndexUniverse LLC. All rights reserved

More From IndexUniverse.com