Five of the Most Amazing Drives from the Back of the Pack

Winning a race is easy. All you have to do is qualify on pole, hold your pace, don't get passed, don't crash, and don't break the car. No problem.

Of course, it's not so simple. Sometimes you lose pace, sometimes the car breaks, sometimes you get passed Quite A Lot, and sometimes all three happen and then you crash. And sometimes you qualify poorly and start out right at the back with the rookies and pay drivers.

Yet this last has a simple solution: just drive the wheels off the car and beat the pants off everybody else. Here are the five best times a racing driver refused to quit, and stormed the field from low down on the grid.

Long Beach Grand Prix, 1983

John Watson sat at the wheel of his McLaren MP4/1, looking at the back of twenty-one other Formula One cars. Qualifying for the Long Beach Grand Prix had gone abysmally for the McLaren team. The only car sitting behind Watson was piloted by former F1 champion Niki Lauda, and even his near-superhuman talents couldn't make pace on the concrete track surface.

The Michelin tires worn by both McLarens simply wouldn't hold heat, suited as they were for the more powerful turbocharged engines that were beginning to dominate F1 podiums. At Watson's back was a naturally aspirated 3.0-liter Ford-Cosworth V-8. It screamed to more than 11,000 rpm and 500 hp, but the engine's roots stretched back to Lotus racing machines from the late 1960s.

However, John Watson had a few cards left to play. For one thing, he's probably the best Formula One driver you've never heard of, with five wins and twenty podium finishes over a career spanning more than a decade. In 1982, he finished third in the championship standings, equalling second-place Didier Pironi in points, and just five points behind winner Keke Rosberg.

For another thing, Watson's MP4 might have been too light in qualifying trim, but with a full fuel load on board, his tires were finally going to find grip. And, lastly, Watson is a Belfast-born Ulsterman, and the people of Northern Ireland have a never-say-die stubbornness to a degree that makes William Wallace look like Jeff Lebowski.

When the flag drops, Lauda got the drop on Watson, and the pair began coursing up the field, snapping up the backmarkers. After twenty-eight laps, they were up to third and fourth, twenty seconds behind the race leaders. Watson made his move, sliding past Lauda, and then taking the fight to the two front-runners.

He was soon past the Williams-Fords of Jacques Lafitte and Keke Rosberg, and managed to hold off his teammate until the finish. The win, Watson's fifth and final in F1, went down in the record books as the win from furthest-back in F1 history, remaining unbeaten today.

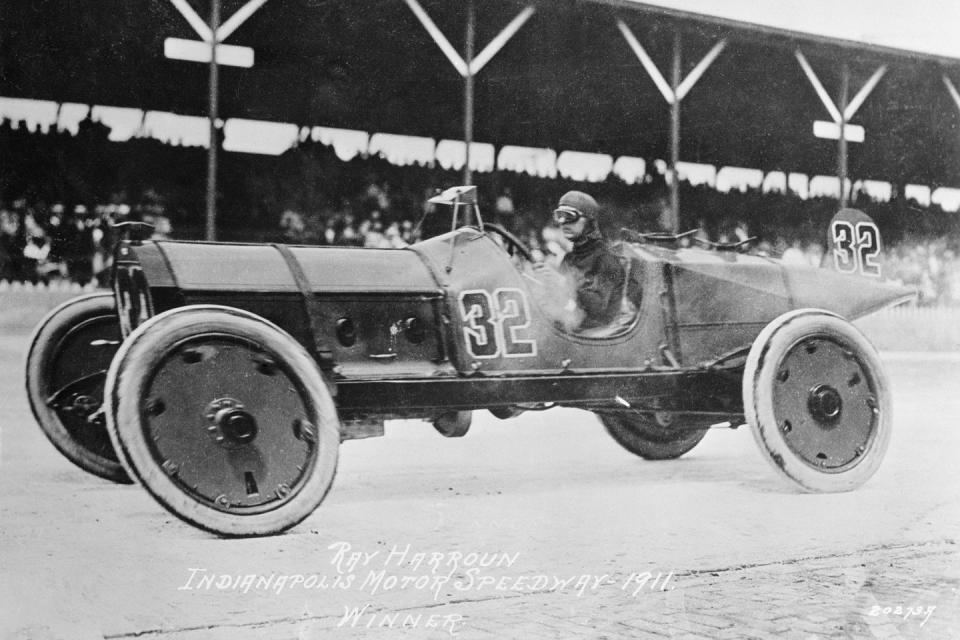

Indy 500, 1911

Qualifying is a test of man and machine. Or, in the case of the very first Indy 500, a test of postman and stamp.

Competitors had to prove a pace worthy of entry into the race, with a 75 mph minimum speed over a flying quarter-mile, but starting positions were picked by the order in which entry forms were received. The unusual decision found pioneering race engineer Ray Harroun sitting six rows back at the wheel of his yellow Marmon Wasp.

Nicknamed “the Little Professor,” for his diminutive stature and academic mien, Harroun considered himself more an engineer than a racing driver. Racing was just the best way to get a good look at how his inventions worked in the field. In the case of the first Indy 500, he'd come up with yet another useful innovation. Thirty-nine of the other entrants had a riding mechanic. Harroun rode alone, having outfitted his Wasp with the very first rearview mirror.

Halfway through the nearly seven hour race, Harroun had put every single one of those competitors in his brand-new rearview mirror. A hard-fought battle with fellow American driver Ralph Mulford marked the second half of the race, but in the end, Harroun emerged victorious. He then retired from driving to focus on the engineering side of racing, presumably never once looking back.

Chicagoland Speedway Indy 300, 2008

As the 2008 Indycar season drew to a close, Brazilian driver Helio Castroneves and New Zealander Scott Dixon found themselves locked in a battle for the championship. On paper, Dixon had victory in the bag by the mid-point of the series, with a 78 point lead over his nearest rival. But Castroneves came charging back, notching up podiums late in the season.

Chicagoland was the last points race of the season, with Dixon having to place eighth or better. To have a shot at the title, Castroneves had to win. Perhaps the pressure got to him, because he made a rookie mistake during qualifying. While posting a respectable fourth-fastest time, he dipped the wheels of his Penske Dallara-Honda below the inside white line, an illegal move. Indycar officials promptly knocked him down to a last place start-28th.

ESPN elected to show the start of the race with two visual bookends: Scott Dixon in second position up front, and an onboard feed from Castroneves, bringing up the rear. You can feel the adrenaline in the footage as the cars circle in formation, the Brazillian champing at the bit, the Kiwi having to stay cool and bring it home.

As the drivers cross the start line, two battles opened up in front of the delighted onlookers. At the front of the pack, Dixon fought to hold his position, dicing it up with the leaders. At the back, Castroneves was clawing his way back up.

In forty laps, Castroneves made up twenty spots. Soon he was in seventh position. And, with just six laps to go on a race restart, it was Dixon and Castroneves, nose to tail.

And then side by side. Inches away at more than 200 mph, the two jockeyed for position, right down to the wire. The finish was so close – thousandths of a second – that initially the call went out that Dixon had won. They even gave him the race-winner's hat as he climbed out of the car. But Helio had it by a nose.

Castroneves' delight at his come-from-behind win was captured on live television, as the results of the photo finish came through. “I knew it!” he shouted, becoming IndyCar's record holder for winning from the furthest back position.

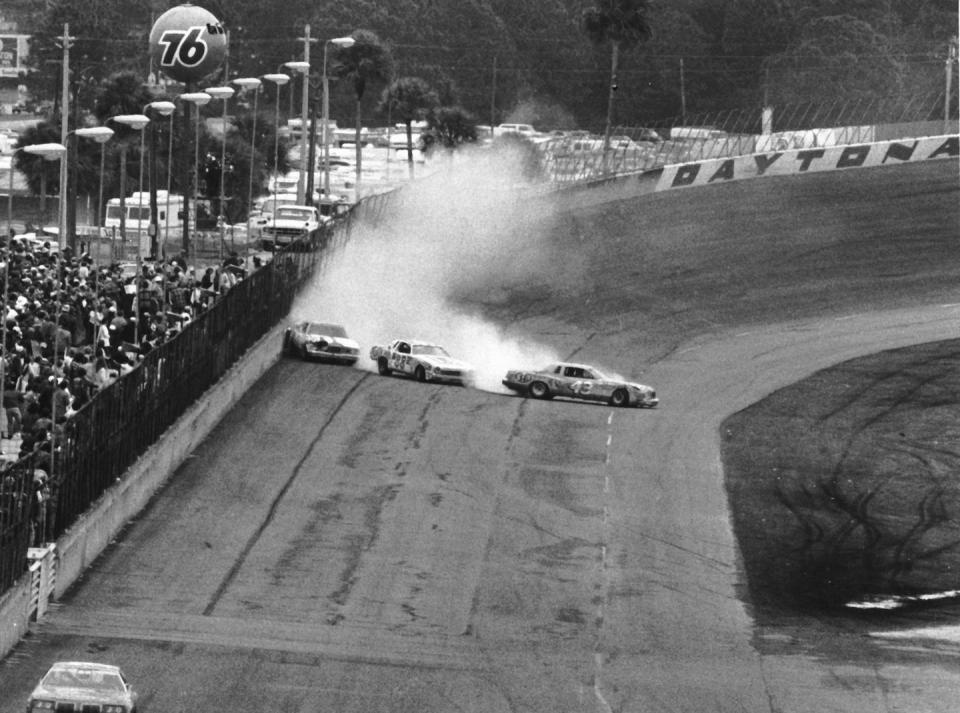

Daytona 500, 1978

The New York Times headline said it all, “Bobby Allison Wins Crash-Filled 500.” Back in the days before restrictor plates and hand-made bodies, stock car racing still had a whiff of moonshine running and mud slinging about it.

If you wanted mud in your eye, Bobby Allison was the guy to put it there. A stock car veteran since the 1950s, Allison showed up at the Daytona 500 with a 67-race winless streak and a thumb he'd broken a month before. He was known to race on local dirt tracks as many as four or five times a week, and the locals loved him for it.

Popular or not, the forty-year old Allison qualified his Ford Thunderbird thirty-third of a forty-one car field, with the likes or Richard Petty, A.J. Foyt, and Cale Yarborough way out up front. Victory seemed unlikely.

But heavy rains the week before made for sketchy track conditions, and the Florida-born Allison was right at home. Also, 1970s tire technology being what it was, most of these guys were basically playing Russian roulette at 180 mph. Petty led half the race in his Dodge Magnum until a tire blew and he wiped out Darrell Waltrip and David Pearson.

Next, A.J. Foyt slowed for a spinning car and got nailed by a close-following Oldsmobile. His Buick flew twenty feet in the air and ended up flipping multiple times in the infield. Rescue crew hauled Super Tex from the wreck and hauled him off to hospital, where he promptly proved his recovery by physically ejecting reporters from his room.

At the track, the race evolved into a heated battle between Allison, Yarborough, and Buddy Baker. Yarborough dropped a cylinder and gave up the lead, and Baker suffered complete engine failure, shaking his fist out the window as Allison cruised by to the win.

Twenty-seven out of the forty-one cars that started the race also finished. The New York Times might have clutched their pearls, but most of the old stock racing veterans considered this to be a pretty low rate of attrition, and about as clean a race as you were likely to see. Allison's furthest-back Daytona record was beaten in 2009, but not in the same bare knuckle, sleeves-rolled-up spirit.

Japanese Grand Prix, 1988

Because of its place in the racing calendar, the Japanese Grand Prix has often been the setting for some of the most dramatic events in Formula One history. Think of the downpour that decided the closely contested championship battle between James Hunt and Niki Lauda, or Alain Prost's controversial championship win in 1989.

And for wins from behind, Kimi Raikkonen's flawless drive in 2005 saw him storm from seventeenth place to a last-lap overtake for the race win. It might just be the Finn's best-ever drive, but to pick one more race to round out our list, we're going to have to come back to a slightly more dramatic day at Suzuka, and the crowning of a legend: Ayrton Senna.

Senna qualified well in the 1988 race, putting his McLaren on pole with arch-rival and teammate Alain Prost sitting in second. It was the eleventh time the front row of a F1 race had been an all-McLaren affair, and the positions neatly lined up with the championship standings: Prost had six wins, Senna seven. If Senna won this race, overall victory was his. But then the flag dropped, and everything was overturned in an instant.

Senna stalled at the start. In seconds he was swarmed, cars hurtling past as Prost rocketed off into the distance.

Yet Suzuka's grid has a mild slope to it, a unique feature on the F1 circuit. Senna managed to get his McLaren bump-started and moved off in fourteenth place, surrounded by a clump of other cars.

Then he got to work. In one lap, Senna made up six positions, putting himself in eighth place, some thirteen seconds back from Prost. He slashed his way up to third place, and it began to rain.

Prost had spent the beginning of the race tied up in a knife-fight with Ivan Capelli's March, but an electrical fault cleared the field. It was Senna and Prost, battling not just for the win, but for the championship.

With Prost leading, the two McLarens caught a couple of backmarkers squabbling over twelfth place. Senna pressed his advantage as Prost lost his momentum to traffic. Despite tires worn by the aggressive charge, Senna slipped past his teammate and held position through slippery conditions to the finish.

It was his first world championship, and an eighth win in a season that bested Jim Clark's long-standing record. Ayrton Senna was at the pinnacle of his career, and he'd driven there from the back of the pack.

('You Might Also Like',)