This Guy Overcame Opioid Addiction and Now He’s Helping Other People Get Sober

After earning a 0.0 GPA and getting expelled from Drexel University, Devin Reaves’ drug use took a dark turn. “I met this girl Tara, and she liked crystal meth a lot,” he says. “It was all fun and games, until it wasn’t.” Reaves was a young black man trapped in an ever-escalating addiction, on a dangerous diet of smoking crack and injecting meth and heroin. From the time he was a teenager, “I just loved to get high,” he says.

On August 20, 2007, Reaves overdosed. By this year, America’s overdose crisis was picking up speed. Hundreds of thousands of overdose deaths have occurred over the last decade. Luckily, Reaves was revived. He woke up in a hospital at the University of Pennsylvania. Was that the proverbial bottom? The cliche “wake up call” that he needed to experience in order to change? Intimately knowing how addiction functions—both physically and emotionally–– and how it’s a condition defined as continually using substances despite all the havoc it wreaks, looking back, Reaves doesn’t think that there is any such a thing as a “bottom.” The plunge could always be deeper, into darker and colder waters.

“Look, my life was shit from 22 to 24,” he said, as a matter of unremarkable fact. “A lot of couch hopping, spending time in Kenso.” That’s short for Kensington, a neighborhood in Philadelphia that the New York Times Magazine once derisively described as the “Wal-Mart of Heroin.” But on that sticky summer day when Reaves woke up inside the hospital, that was the day he entered treatment for the first time. “Rehab was my only option,” he said. “I had no place else to go. It’s not like I wanted to get well, it was just the least sucky option I had.”

Inside treatment, Reaves saw the toll that addiction took on the lives of men much older than him. He realized, at 24 years old, how much life he had ahead of him. Light began to shine through the dark waters, and for the first time in a long time, he could see a bright horizon.

“The funny thing about recovery is that it’s contagious,” he said. “You start seeing other people who had the same problem you had, who are doing well and living a good life. It gets you thinking, ‘Hey, maybe if I didn’t do drugs, I would have a college degree?” He saw that he fell behind his peers, who were in serious relationships, who had steady jobs, nice apartments, and were starting to settle down.

But recovery looked good on Reaves, and day by day, life felt a little easier, a little lighter. Inside treatment, he confronted the impact that his father’s addiction had on him, and what it felt like growing up with a single mom. He did the exhausting work of unpacking his relationship with drugs, understanding what kind of emotions and traumas that the chemicals covered up. He began to feel his feelings without reaching for a drug to numb them.

While working at a beauty supply store, stocking shelves, somebody suggested that he go back to college. “At school, I saw a sign that said ‘Get your master’s in human services’ and get an entry level job at a rehab. I thought, ‘That’s what I’ll do. I want to help people like the way I was helped.’” Then his professors suggested that he get a master’s in social work, and so he did.

Reaves applied to a bunch of schools, some in Florida, and others in Pennsylvania. “I got accepted into them all, including my reach school, University of Pennsylvania.” Less than five years after he overdosed, Reaves was now getting his master’s at the same place that saved his life. “Talk about coming full circle,” he said, laughing.

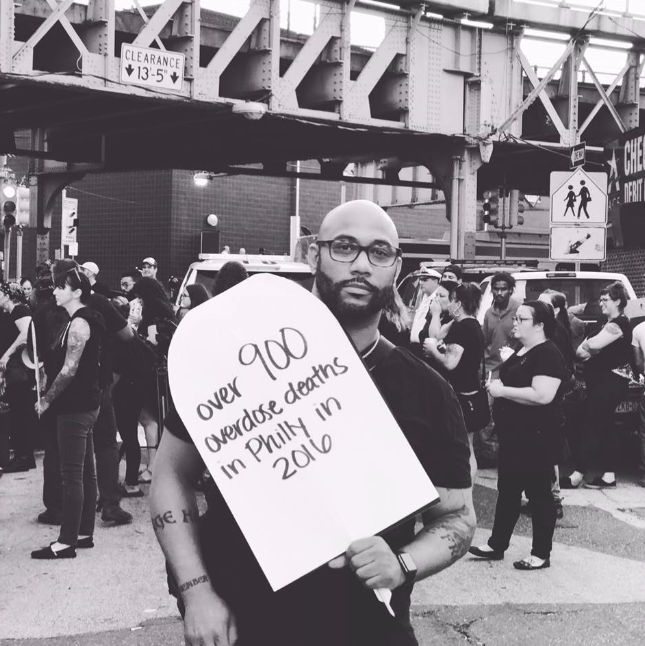

Hearing Reaves tell his story, there’s an unmistakable groundedness and confidence to his demeanor. “I’m killing it right now,” he says, referring to the nonprofit that he runs, called the Pennsylvania Harm Reduction Coalition. But he also has the awareness that addiction narratives tend to be hyper-individualistic. “Look, I had insurance. My mother had money. This was all in 2007, pre-ObamaCare, before every 24-year-old was on their parents’ insurance,” he said. “I was blessed to have access to these resources.”

Today, Reaves is 36 years old and has a family. He and his wife Ashley have a daughter, and another on the way. His relationship with his mother his strong again. All this keeps him going. But he’s also staying healthy so he can fight to make sure everyone can have the experience he had. “Let’s face it,” he said, “drug use is not seen as a problem until it lands in suburbia. And the poor folk, the people going to jail, they look like me.”

“As a black man running a drug policy advocacy organization, I want to build a system that seeks to liberate communities from the War on Drugs,” he said. “We’re going up against all these things: structural racism, the power of the criminal justice system, the War on Drugs. We’re actually looking at our friends die. And if we’re not supporting each other’s own mental and physical health, we’re not gonna make it.”

You Might Also Like