What This Holocaust Survivor Wants Americans To Understand About The Resistance

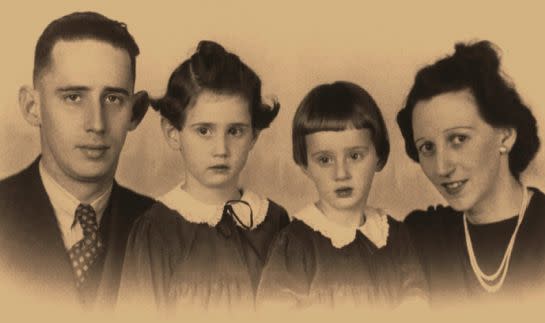

Maud Dahme was only four in 1940 when the Netherlands, where she lived with her family, was invaded by the Nazis. She was six years old when she went into hiding with her sister Rita, who was two years younger.

“I remember the bombings and the sirens going off, and having to go in a basement until there was an all-clear sign. That’s probably what stands out most from my childhood and the danger at that time,” she told HuffPost from her home in Flemington, New Jersey.

Dahme, now an 82-year-old retired school board administrator, is as concerned with the events prior to her hiding ― an escalation of hateful imagery and anti-Semitic rhetoric ― as those during and after.

“It frightens me because I’ve seen how these things just build and build to something awful,” she said.

Dahme’s family was Jewish. She was born in The Netherlands, and at the time, many Jewish families were fleeing to the country from Germany. Dahme remembers wearing a yellow star as a child, but she didn’t know what it meant. At the time, it made her feel proud. She had just become old enough to wear it.

In 1942, Dahme’s parents sent her and her sister into hiding, telling them that they were going on vacation with family. Instead, the sisters were placed with a religious Christian couple in their 60s with no children, Hendrik and Jacobje Spronk. Maud and Rita’s names were changed to Margie and Rika.

The sisters were in hiding for three years before the war ended. They learned that their parents had been hidden and survived. In 1950, the family, sponsored by family members in the U.S., made their way to America.

Dahme’s message today is the same as it’s been for 30 years: without any effort toward respect and understanding, what happened before can happen again.

“I’m just hoping and praying that people will have better understanding of each other, and really respect each other more than anything,” she says. “You don’t have to have the same religion, or you may have an accent, or you may have blue hair and green eyes, but inside, we’re all the same.”

“I tell students they have to care,” she says. “I wouldn’t be here today if people didn’t care to save my sister and me.”

Dahme recalls being stunned watching the news coverage of the neo-Nazi and white supremacist rallies in Charlottesville in August. “Watching television and seeing what was happening in Charlottesville ― it broke my heart,” she says.

Though Dahme was just six years old when she went into hiding, she remembers she had a sense that things were changing.

“As time went on during those years, in hiding, of course I began to understand more and more and seeing more and more things. You know, it started out with just a little thing, and then it was the next thing and the next thing and next thing,” she says.

For all she has seen and survived, Dahme has faith in kindness. She now urges Americans of all ages not just to remember the unimaginable horrors of the Nazis, but the unimaginable kindness that kept so many alive.

When she speaks with students and teachers, she makes sure they understand not only the plight of those who were persecuted but the courage of those who risked everything to help. It is their blind kindness in the face of hate that we need to remember now more than ever, Dahme says.

“Now, at this time, I think it’s so important for people to hear the stories and how people cared. When I speak to students, I don’t talk about the atrocities that I’ve seen and things that have happened to me. Yes, I tell my story, but it’s positive,” she says. “I think it’s very important to remember that it was a time in history when millions of people died and only because of their religion, and there’s also the other side of the story, which is how many people cared and were willing to risk their lives to save Jews and anyone else.”

Now, Dahme speaks with students and teachers about her life. She published her memoir, Chocolate: The Taste Of Freedom in 2015. She works with Stockton University’s Sara and Sam Schoffer Holocaust Resource Center. Every year, she leads a group of teachers on a trip to Holocaust historical sites throughout Europe.

It’s important for educators to “see these camps, and actually feel it, smell it,” she says. “It changes everyone. It changes all the teachers, but the most wonderful thing is they bring all this back to the classroom, and all their students benefit from all that they have witnessed and learned,” she said.

Dahme discovers something new every time she goes to Europe. Stories and items from her history, people and things she thought were long gone, are constantly revealing themselves.

During an August trip to Amsterdam, she visited a woman who helped take care of the Spronk farm when Dahme was in hiding. Her name was Ditte Spronk, and they’d reconnected five years ago. Ditte was in the hospital; she was dying. She had an envelope.

“I opened the envelope, and there was a little child’s fork in there. On back of the fork was inscribed my name,” Dahme said. “My mother gave me a spoon and a fork when we went into hiding in 1942, and somehow all these years later, it was found. ”

Love HuffPost? Become a founding member of HuffPost Plus today.

This article originally appeared on HuffPost.