'I go hungry': What parents are sacrificing amid soaring inflation to feed their families

At least once a week during dinner, Cathy Smith and her husband, Robert, are confronted with the same choice: Don't let the kids have seconds or forgo a meal themselves.

“I have growing children, and I want to make sure they have enough portions to nourish themselves,” says Smith, 40, a mother of five who works at an Atlanta-area school district as a recruiter. “It’s to the point that we have stopped buying cereal because milk is so expensive.”

American families, like the Smiths, who spend most of their income on necessities such as groceries, gas and rent are struggling as inflation, at 8.3%, remains near 40-year highs and consumer prices surge.

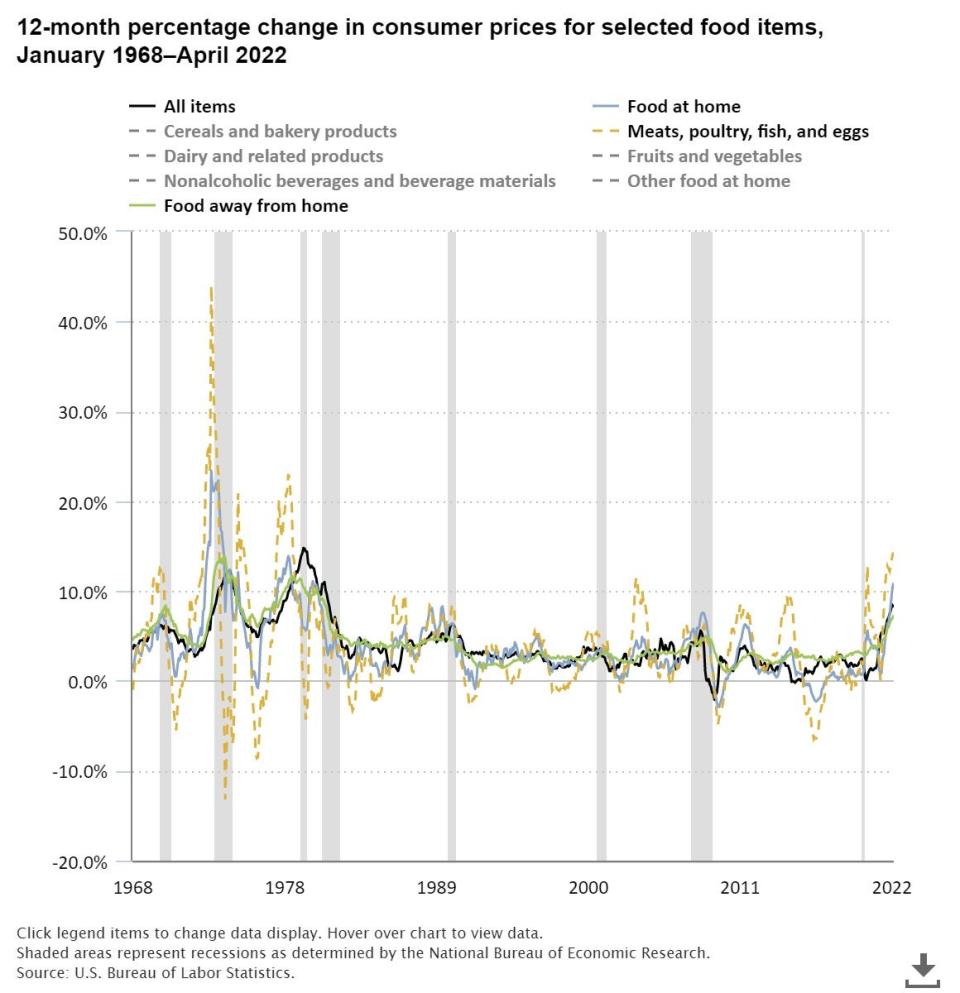

Last month, "food at home" prices jumped 11%, the largest 12-month increase since November 1980, according to data released by the Labor Department this month. The cost of gas remains high, and shelter costs have been steadily creeping up.

Though wages and salaries increased 5% for private sector employees amid worker shortages from March 2021 to March 2022, the nearly 20 million state and local government workers saw their wages go up by only 3%, according to the latest Labor Department’s Employment Cost Index.

Text with the USA TODAY newsroom about the day’s biggest stories. Sign up for our subscriber-only texting experience.

Inflation and a diminished quality of life

Amid rising costs, many families with children are feeling particularly overwhelmed.

Small, quality-of-life pleasures they could afford before the pandemic have fallen by the wayside for many. Whether it is a mother pulling her child out of a ballet class or a family deciding to forgo road trips, the stories of sacrifice are becoming commonplace.

Smith earns $67,000 a year. Her husband, who is pursuing a master’s degree and works part-time as an Uber driver, brings home about $20,000 to $30,000 a year.

She says she "makes too much for assistance" but too little to get by.

“My kids want to meet friends and travel places, things that you would think someone with my income living in Georgia would not have a problem with,” Smith says. “All the prices are inflated, but my salary hasn’t gone up.”

No scope for substitution

Earlier this month, the Federal Reserve raised its short-term interest rate by half a percentage point – the most in 20 years – to cool demand and tamp down inflation. President Joe Biden recently said fighting rising prices is his “top domestic priority.”

Inflation has most hurt low-income families, who spend a large share of their budget on gas and food, says Allison Schrager, an economist and senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank.

Unlike high-income families, who could stop ordering takeout or replace a $30 bottle of wine with one that costs $20, low-income families often have few options for substitution, Schrager says.

“They were already doing everything they could to get by,” she says. “If you're a low-income person, you are already probably shopping at the cheapest place possible. So you don't have a lot of scope to change your behavior.”

But it's not just low-income families who are suffering. Most people USA TODAY spoke to for this story were making between $65,000 -$100,000, a bracket considered solidly middle-class, according to the yardstick used by the Pew Research Center.

Monetary and fiscal policy changes needed

Schrager says that while the Fed raising the interest rates is a good thing, she believes some changes in fiscal policy such as expanding trade and relaxing immigration could curtail inflation in the medium to long term.

“Some of this is pandemic-related and will go away when the world gets back to normal, but the longer inflation lasts, the more it gets into the bones of an economy," she says. "And then it's really hard to get rid of.”

Candice Seawright, 35 and a single mother of two from Stamford, Connecticut, recently pulled her 8-year-old daughter out of dance lessons in Harlem, New York.

“She loved going and she's very upset,” says Seawright, a teaching assistant at the Mount Vernon School District in New York. “But I can't pay the tuition fee and pay for the gas.”

Seawright says she used to be able to fill a grocery cart for $200, but now it’s more than $300 for the same amount of food. She has stopped dining out with her children and her mother.

“Even the cost of fast food has gone up," she says. "I just feel like all my money is going to gas or rent.”

She also is behind on her credit card payment for the past month and is worried it will affect her credit score.

“I don't like to put my credit cards on the back burner,” she says. “But I have to make sure I have food, and gas, and that my rent and electricity bill is paid before I can pay my credit card bills.”

That has also been the experience of Nicole Cardoza, a single parent from Sacramento, California.

Cardoza, a grant writer for a nonprofit who earns $66,000 a year, hasn’t been able to pay her credit card bills the last couple of months.

“You have a budget and then the cost of gas and the cost of groceries almost double,” says Cardoza, whose daughter has cerebral palsy. “Normally I can pay off my credit card every month, and I can't do that right now. ”

Cardoza says she has always been financially conservative because of her daughter’s condition.

“Anything can happen with her that is financially catastrophic with her at any time,” she says. “So I’ve always tried really hard to live within my means.”

The supply chain interruptions during the pandemic meant she couldn’t find the special diapers for her daughter at her provider’s office and instead had to buy them from a local medical supply store at a big markup.

On weekends, she searches for free things to do with her boyfriend, such as hiking nearby. She hasn’t been to a movie theater even though she wants to see the new Marvel movie. She has given up wine tasting and yoga lessons. Her daughter's 13th birthday party was a low-key affair.

“It’s like you're having to like let go of all these things that sort of enhance your life,” she says.

For Cathy Smith, the mom of five, it’s been hard trying to navigate the new reality.

“I go hungry. It's an easy decision to make as a parent between them and me,” she says. “But it’s a decision that shouldn't have to be made. It shouldn't come down to that.”

Swapna Venugopal Ramaswamy is a housing and economy correspondent for USA TODAY. You can follow her on Twitter @SwapnaVenugopal and sign up for our Daily Money newsletter here

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Inflation, rising food prices leave US families skipping simple joys