ICE expands controversial partnerships with local law enforcement

Bernardo Gabriel has always had faith in law enforcement.

A few years after his family crossed the border from Mexico in 2004, he called the cops to report his father for beating his mom.

The police intervened, his dad got deported and Gabriel and his family eventually received U-visas, reserved for undocumented victims of crimes who cooperate with police.

Thanks to the U-visa, he was able to work, pay taxes and eventually get a green card. Outside his full-time job in sales and customer service at an online jewelry store, Gabriel is a volunteer firefighter and is taking classes to become an EMT. In a little over three years, he’ll be eligible to apply for citizenship — if he doesn’t get deported first.

Last summer, Gabriel found himself in another domestic violence situation when his wife became violent during an argument, punching him several times while he was driving with one of his nephews in the car. He says he pulled over and called the police, hoping they could help him defuse the situation. But when the cops arrived, Gabriel says his wife accused him of assaulting her and he was the one who wound up in handcuffs.

Because he was arrested in Frederick County, Md., where sheriff’s deputies have been engaged in a partnership with Immigration and Customs Enforcement to help enforce federal immigration law since 2008, Gabriel was asked about his immigration status upon being taken to the local jail/detention center.

Gabriel says he was released that day without bond and when he showed up to court, the prosecutor decided not to pursue the case. He was relieved, but even though the case was cleared, his information had already been entered into ICE’s system, and when he returned from visiting his family in Mexico in February, Gabriel discovered that the incident had repercussions. He says he was pulled aside while going through customs and told by an immigration agent that if he gets arrested again, he’ll be deported.

Gabriel’s story is just one example of the real-life ramifications of the 287(g) program, a long-standing and controversial federal program that trains and deputizes state and local police officers to enforce some aspects of federal immigration law. Participation in the program has varied over the years, but is being revived under the Trump administration. Gabriel had the misfortune to live in one of a small number of jurisdictions — a total of 78 in 20 states, double from a year ago — that are currently enrolled.

Such ICE partnerships exist in both rural and urban areas across the United States, though a large percentage of jurisdictions currently enrolled in 287(g) agreements are located in the Southeast — and in Texas, where 18 county sheriff’s offices have enlisted since last year.

The communities they cover range greatly in size and demographics. The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department, for example, serves the approximately 2 million people living in Nevada’s Clark County, 22 percent of whom were born outside the U.S. But in Goliad County, Texas, which is home to just over 7,000 people total, just 2 percent are foreign-born.

The blandly branded 287(g) program dates back to 1996, when it was enacted as part of that year’s Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (known by the equally catchy abbreviation, IIRAIRA). Through the program, state and local law enforcement agencies request a written agreement with the Department of Homeland Security to deputize — under ICE supervision — a select few officers within their agencies (who must be U.S. citizens with at least a year of law enforcement experience) to enforce federal immigration laws in addition to their regular police duties.

After undergoing four-week ICE training (followed by a required refresher every two years), deputized officers are generally authorized to question individuals about their immigration status, check DHS databases for such information, transfer non-citizens into ICE custody and launch deportation proceedings by issuing official Notices to Appear in immigration court. They are also able to enter personal data into the ICE database, recommend non-citizens for detention and immigration bond as well as voluntary departure and issue requests for immigration detainers to hold people until they can be taken into ICE custody.

Over the past 22 years, the 287(g) program has undergone a number of changes. Federal funding for the training and oversight aspects of the program peaked under the Obama administration between 2010 and 2013, then declined as some local agencies chose to withdraw, citing among other factors the program’s high cost and relatively little emphasis on serious criminal offenders, among other concerns.

Historically there have been three types of 287(g) agreements: the “task force model,” which allowed deputized officers to question and arrest alleged non-citizens who they encounter during the course of their daily police activities; the “jail enforcement model,” under which deputized officers may only interrogate and initiate removal proceedings for suspected non-citizens who’ve been arrested on other charges; and the “hybrid model,” which combined aspects of both.

But at the end of 2012, amid concerns about the program’s effectiveness and potential for abuse, ICE announced it would discontinue the task force and hybrid models. To the relief of some 287(g) opponents, that decision has remained in place under the Trump administration. All of ICE’s current 287(g) agreements now operate under the jail enforcement model.

While proponents of the program insist it primarily targets serious criminals or threats to national security, various reviews of the program’s implementation over the years have found that not to be the case, including an oft-cited 2011 report by the nonpartisan think tank Migration Policy Institute, which concluded that “about half of 287(g) activity involves non-citizens arrested for misdemeanors and traffic offenses.”

A more recent study published by the libertarian Cato Institute in April zeroed in on several counties with 287(g) programs in North Carolina and found that the program had no impact on the crime rates or police clearances in those counties. When the Knox County [Tenn.] Sheriff’s Office applied for a 287(g) agreement, not one of the crimes they listed under “top five arrest charges for foreign-born individuals” was a violent offense, and four of them were driving-related.

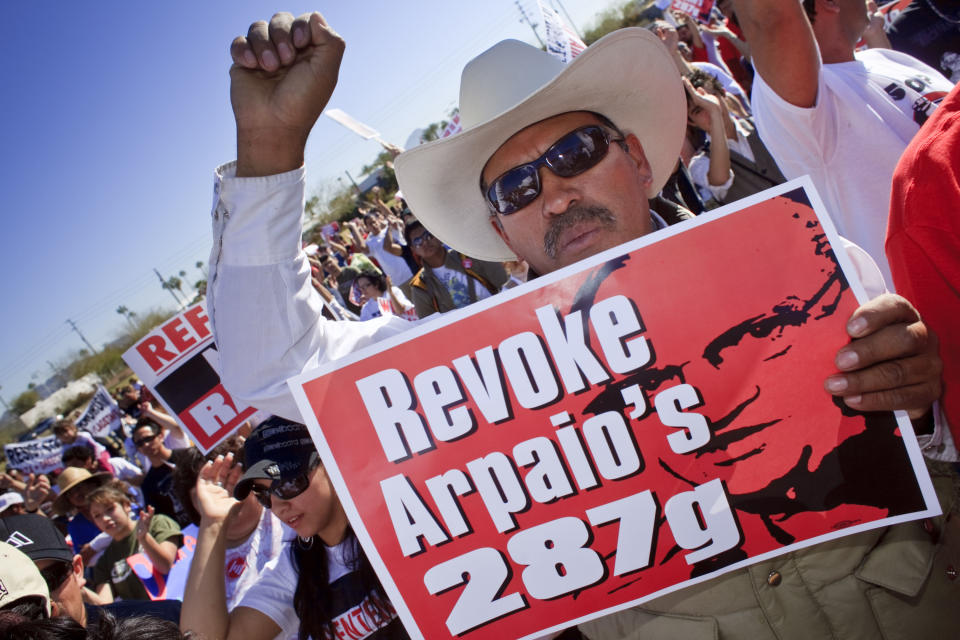

For some police agencies, however, the program seemed to provide both permission and the tools necessary to pursue their anti-immigrant agendas. ICE was forced to sever ties with Arizona’s Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office when a Justice Department investigation found that, after entering a 287(g) agreement, deputies of notorious former Sheriff Joe Arpaio had engaged in a pattern of constitutional violations, including racial profiling.

ICE terminated an agreement with the sheriff’s office in Alamance County, N.C., after a separate investigation found evidence of similar practices directed against Latinos.

By 2014, federal funding for 287(g) had dropped to half of what it had been during the previous four years, as other programs were deemed to be more effective. Still, it always remained in use, and toward the end of Obama’s tenure, ICE had begun to slowly rebuild its list of state and local partners while agency leaders set out to reexamine the program’s historically opaque system for vetting applications by local jurisdictions.

A former ICE official familiar with this review told Yahoo News that the analysis revealed a “weak” application process requiring remarkably little evidence of a department’s need for the authority to enforce immigration laws.

ICE policy explicitly prohibits racial profiling under 287(g). But such a low barrier to entry, compounded by some of ICE’s own language on the application itself seem to undermine, if not contradict, this rule. A former ICE official told Yahoo News he was troubled by a reference on the application to “foreign-born criminals” and “foreign-born gang members.”

“Why are we identifying foreign-born gang members?” the former ICE official asked, noting that plenty of foreign-born people may be citizens or otherwise legally authorized to be in the country.

“Being foreign-born doesn’t really get to root of the underlying problems of immigration and customs enforcement,” suggesting something like “foreign nationals,” might be more appropriate. Instead, ICE’s language seems to paint anyone who may have been born outside the U.S. as a person of interest.

“That’s when you start getting into this idea of profiling, because you’re looking for ‘foreign-born’ individuals,” the former official said.

The program has also proven to be ripe for political exploitation, with a large majority of 287(g) partnerships being pursued by sheriffs, generally an elected position.

The former ICE official told Yahoo News that the agency had been considering ways to make the 287(g) vetting process stricter, more transparent and less vulnerable to political exploitation or racial bias, but the project ended with the Obama administration.

Less than a week after Trump took office, he called for expanding the 287(g) program in his executive order on Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States.

During a panel discussion at the Justice Department last week, Nathalie Asher, assistant director of ICE’s Enforcement and Removal field operations, promoted the recent growth of 287(g) and plans for further expansion. With her on the dais was a small group of sheriffs touting their own jurisdictions’ success with the program. Among them was Sheriff Chuck Jenkins of Frederick, Md., where Bernardo Gabriel was arrested.

Jenkins called 287(g) a “flawless” program, and stated that in the 10 years his department had been collaborating with ICE, he hadn’t received a single complaint of racial profiling.

Nick Steiner, legal & public policy counsel of the ACLU of Maryland, said the lack of transparency around 287(g) has made it difficult to track complaints of racial profiling against the Frederick County Sheriff’s Office, but the idea that there have been none “is just beyond belief.”

Frederick County’s 287(g) program plays a role in an ongoing wrongful arrest lawsuit brought by Roxana Orellana Santos, a Salvadoran who was arrested in 2008 after two sheriff’s deputies reportedly questioned her about her immigration status while she was eating lunch outside her workplace. In 2013, a federal appeals court affirmed Santos’s argument that the deputies violated her constitutional protection against unlawful search and seizure, ruling that state and local authorities cannot arrest someone simply based on suspicion that they are in the country illegally.

Now the case is back in Maryland District Court, where Jenkins and county officials are claiming that they should not be held liable for Santos’s unlawful arrest and subsequent 37 days in jail. Attorneys for Santos argue that her arrest was the result of the county’s 287(g) program. Jenkins has maintained that the Santos case had nothing to do with Frederick County’s ICE partnership, noting that the deputies involved were not trained under the county’s 287(g) program, which operates under the jail enforcement model. But attorneys for Santos have argued that her arrest is proof that the program leads to racial profiling.

Last year, University of Tampa economics professor Michael Coon published the results of a study that examined the impact of Frederick County’s 287(g) agreement after it took effect in 2008.

The study compared the monthly arrest rates from 2006 to 2014 for whites, blacks and Hispanics by the Frederick County Sheriff’s Office and for the Frederick [City] Police Department, which is not engaged in a partnership with ICE. While Frederick County’s Hispanic population actually grew during that time period, Coon found that arrests of Hispanics by both city police and sheriff’s deputies significantly decreased relative to arrests of blacks and whites. Given that crimes most commonly involve victims and perpetrators of the same race, Coon inferred that the implementation of 287(g) in Frederick County had a chilling effect, leading fewer Hispanic residents to report crimes to avoid any interaction with law enforcement.

Jenkins dismissed the report as “nonsense” at the time.

But a variety of other research has highlighted similar trends in other communities with 287(g) agreements. One study by the University of North Carolina School of Law and the ACLU of North Carolina found that, among other issues, the implementation of 287(g) programs in North Carolina had resulted in “a fear of law enforcement that causes immigrant communities to refrain from reporting crimes, thereby compromising public safety for immigrants and citizens alike.”

In Maricopa County, neighborhood “sweeps” and other aggressive efforts to pursue illegal immigrants not only eroded trust between the community and local law enforcement, but also led the sheriff’s office to neglect its other law enforcement duties, allowing a rash of alleged sex crimes, including child molestation, to go virtually ignored.

Of course, Maricopa is one of, if not the most, extreme example of 287(g) gone wrong. Supporters of the program insist racial profiling is generally not a problem.

“I understand there have been some agencies that have pulled out of the program, some that have been removed from the program for reported abuses, but [I] don’t see it as a problem,” said Sheriff A.J. Lauderbach of Jackson County, Texas. Lauderbach, who participated in last week’s panel, is one of 18 Texas county sheriffs who launched 287(g) partnerships with ICE last year. He praised the program as “in the best interest of public safety.”

Jonathan Thompson, head of the National Sheriffs Association, also dismissed the idea that there’s any link between 287(g) agreements and racial profiling, suggesting reports associating the program with such abuses amount to “someone trying to make story out of something that doesn’t exist.”

“There’s always going to be abuses of any system whether it’s news reporting or law enforcement,” Thompson told Yahoo News. “It’s very clear in every agreement that they sign what the expectations are. They have to follow the laws and the Constitution.”

Asked to comment on ICE’s current effort to expand 287(g) partnerships with state and local law enforcement, Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone, who unseated Arpaio after 24 years last fall, acknowledged the potential public safety benefits of sharing resources with a federal agency like ICE, but emphasized the need for local law enforcement agencies to “to stay true to our individual missions with an unwavering commitment to lawful practices.”

“The 287(g) program may provide benefits to address the challenging issue of enforcing immigration laws, yet it is the abuse of this authority that has led to the existing restrictions on my office and the men and women tasked with delivering public safety,” Penzone said in a statement to Yahoo News. “Ultimately, our community now pays a much greater price, both financially and in law enforcement resources, as we work to restore the office to full capacity without the federal oversight.”

Unlike Penzone, Sheriff Terry Johnson of North Carolina’s Alamance County is eager to rejoin the program five years after he and his office had their 287(g) agreement terminated over allegations of racial profiling.

Johnson told the Burlington Times-News last year that ICE had approached him about rejoining the 287(g) program and “I immediately agreed.” ICE does not disclose pending applications, and has yet to confirm whether it will, in fact, renew its partnership with Alamance County.

Asked at last week’s panel about Alamance County and other jurisdictions that may seek to resurrect 287(g) agreements, ICE’s Asher did not address any specific jurisdictions but insisted that “ICE takes very seriously any misconduct” and “we do not promote racial profiling.”

But the former ICE official predicted that, without imposing a more stringent vetting system, any effort to expand 287(g) amid the current climate would “absolutely” attract more sheriffs and other law enforcement leaders who seek to exploit the program for their own personal bias or political gains, and warned ICE leaders to be cautious as they recruit new partners.

“If you start seeing a flurry of 287(g) requests, I think you have a responsibility to the community, to the greater community, to ensure that they’re entering into this agreement for the right reasons; to go after actual criminal threats to society, criminal threats to the community at large, and not to profile.”

For Bernardo Gabriel, his experience has forced him to “think twice if I want to call the cops” for help again. “Who is going to get arrested, me or the actual offender?”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: