Internet pioneer Vint Cerf: We need to make room on the Net for all the machines

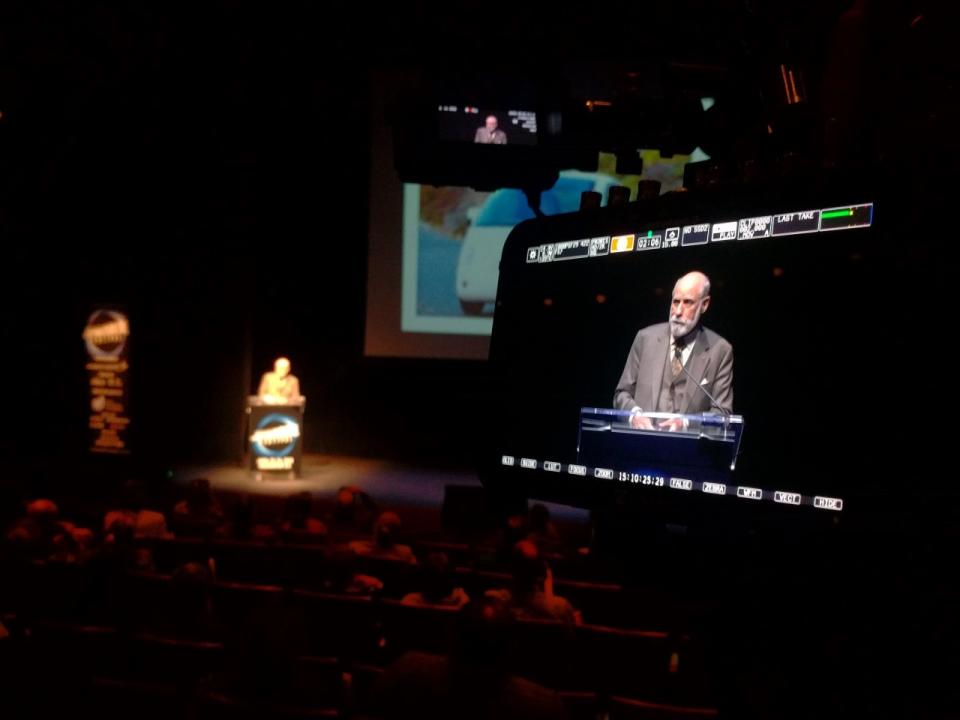

(Photo by Rob Pegoraro/Yahoo Tech)

The Internet is unlike many other major human inventions in one way: Most of the people who helped create it are still around. So if you have a chance to hear one of them talk, you should take it.

One such opportunity brought me to downtown Washington Saturday to hear Vint Cerf — co-author of the Internet’s core TCP/IP framework and Google’s “Chief Internet Evangelist” — talk about how his baby has grown up and where he thinks it will be in another 20 years.

Cerf was part of a long lineup at Smithsonian magazine’s “The Future Is Here” festival, a gathering that last year featured an onstage demo of Arx Pax’s Hendo hoverboard (it actually hovers instead of rolling around on wheels and then catching on fire) and a surprisingly optimistic take on robot soldiers. Beyond Cerf, this year’s speakers included William Shatner; I may have to turn in my nerd credentials for missing his appearance.

Big to little, little to big

It’s easy to forget how bulky computers once were, but Cerf reminded the audience at the Shakespeare Theatre Company’s Sidney Harman Hall of the Internet’s unwieldy origins by showing photos of a closet-sized router and a van stuffed with communications hardware for experiments in packet-switched voice communication.

“Big, expensive things eventually get cheaper and smaller until they are personal things,” said Cerf, sharply dressed as usual in a three-piece suit. “The thing you carry in your pocket once took an entire van to do.”

For the most part, the Internet has scaled amazingly well from those origins. Or as Cerf said: “It’s a miracle whenever software works.”

But the co-author of protocols on which the Internet still relies — Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and its companion Internet Protocol (IP)— admitted that they baked in one mistake: The current version of the IP only allows 4,294,967,296 distinct addresses at a time for devices on the Internet.

“In 1973, that sounded like more than enough to do an experiment,” Cerf said. Years ago, work began on a new version, “IPv6,” that can accommodate a full 340,282,366,920,938,463,463,374,607,431,770,000,000 addresses — “a number only Congress can appreciate,” he added.

Despite its importance, this switchover has received little attention. (My own desperate attempt to publicize it in 2011 with a hypothetical example involving Katy Perry and Lady Gaga fell flat.) But Cerf made his own pitch: “Go ask your service provider, when can you give me an IPv6 address?“ I have to admit, I have no idea if mine even can.)

So many devices

Cerf said we’ll need such an enormous number of IP addresses to accommodate all the devices coming online — from 10 to 15 billion today to 1 trillion in 2036. In the same time period, he said, the number of people using the Internet should grow from “only” 3 to 3.5 billion to 8 to 10 billion.

He cited the example of his wine cellar. At first, he only had temperature and humidity sensors there. He then he added RIFD tags to each bottle. Then he figured he might as well put a sensor in each cork to see if the wine in a bottle had begun to age poorly. The advantage all these networked sensors provide: “You can give the bottle to somebody who won’t know the difference.”

Cerf walked the audience through some other Google projects that will put more hardware on the Internet: smart contact lens for diabetics that can measure the level of glucose in your tears and “ingestible robots” that “could crawl around your vascular systems and make corrections.”

“Now, this is not nuts,” Cerf assured an audience that may not have been convinced by that statement.

Cerf then spent some time discussing Google’s project to develop self-driving cars. He voiced more caution about that than I’ve heard from other Googlers, saying “We are far from having a car that can drive under all conditions.” Cerf noted that one test vehicle recently had a 3-mph scrape with a bus in San Francisco.

But Google’s driverless cars will get better because they can share their lessons learned in real time.

“The cars learn from each other… something that our human being drivers don’t ever do,” he said. Unsaid by Cerf: That human drivers tend to overstate both their own competence and their risks of losing all control to robots.

Cerf also touched on augmented reality (he sees a bright future for Google Glass in helping surgeons at work, something I saw an Austin, Tex. startup called Pristine pitch at the Demo conference in 2013) and virtual reality (he thinks today’s headsets make us “look like Darth Vader” and expects 3-D holograms will take their place).

To the stars

Cerf closed with a favorite subject: interplanetary Internet, a set of Internet protocols adapted to ensure delivery of data over millions or billions of miles.

NASA has been using it since 2008, and today it helps connect Mars probes to Earth. As more spacecraft go online and build out this network, Cerf predicted, “we’ll accrete an interplanetary backbone.“

And if a new venture by physicist Stephen Hawking and Russian investor Yuri Milner to send a light-powered probe 4.37 light years to Alpha Centauri succeeds, the interplanetary Internet can become interstellar.

“I won’t live to see this thing get there or even launch,” Cerf said. “But when you’re working on stuff like this, it’s like living in a science-fiction story and it’s really a lot of fun.”

Email Rob at rob@robpegoraro.com; follow him on Twitter at @robpegoraro.