'It is legal extortion': Diabetics pay steep price for insulin as rebates drive up costs

In 1921, Canadian scientist Frederick Banting discovered insulin and later sold the patent to the University of Toronto for $1, declaring that the lifesaving drug did not belong to him. "It belongs to the world."

One hundred years later, the 8.4 million diabetics in the USA who rely on insulin pay an exorbitant amount of money for a drug that supposedly belongs to them.

As the cost of insulin has risen – average list prices increased 40% from 2014 to 2018 – patients and their families shell out hundreds of dollars a month even when they have good insurance. They pay other bills late to keep their insulin-dependent children alive. When they can't make ends meet any other way, they ration their medication, often ending up in a hospital because they could afford only a fraction of the insulin they were supposed to use that month.

"It is legal extortion," Rod Regalado, father of a teen with Type 1 diabetes, said about the opaque insulin pricing system.

What's next for interest rates?Fed chair may offer clues on inflation curbs as Ukraine war escalates

Helping hands: Airbnb nonprofit to offer free housing to 100,000 refugees from Ukraine

A bill that would create a federal cap on monthly insulin out-of-pocket costs is named after his son. Matt's Act would cap insulin prices at $20 to $60 a month or even $0 for those with high-deductible health plans. Similar provisions are included in the House-passed version of the Build Back Better Act, which proposes an insurance co-pay cap of $35 for insulin.

Struggling to stay alive: Rising insulin prices cause diabetics to go to extremes

The bills attempt to simplify costs for consumers who are kept in the dark when it comes to the complex negotiations driving insulin prices up.

"If you or I were buying a gallon of milk from Kroger or whoever, if we saw that it was $20, we would know that we're getting ripped off," said Antonio Ciaccia, former lobbyist for the Ohio Pharmacists Association and CEO of 46brooklyn, a drug price research firm. "The gallon of milk stays within a slightly competitive range because we know where we could go elsewhere to find a $3 gallon."

That competitive price pressure doesn't exist in health care, he said. "Because we as cash-paying customers aren't the predominant source of revenue for health care."

Fear of exclusion drives list prices up

In a report on insulin prices released in January, the Senate Finance Committee laid out the numerous factors that combine to make insulin so expensive.

The committee found that drug manufacturers continually increase insulin's list price to offer larger rebates to pharmacy benefit managers and health insurers, “all in the hopes that their product would receive preferred formulary placement,” the report said.

Pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs, oversee the prescription drug part of health plans – negotiating with drugmakers for bulk discounts and deciding which drugs will be covered and which will be excluded from their formularies or approved drug lists. Their clients are health insurance plans, including employers and government-run Medicare and Medicaid.

No drugmaker wants to be left off the preferred list of a big PBM such as CVS Caremark or Express Scripts, because tens of millions of Americans are covered by insurers using their services.

This pricing structure exists for almost every drug on the market, but insulin has gotten focused attention because of the number of diabetics that rely on the lifesaving drug and the fact that it's 100 years old yet getting more expensive every year.

Health care costs: Seniors' care suffers due to skyrocketing fees for prescription drugs, pharmacists say

Drug prices: Patients can't count discounts toward health insurance deductible

"They're kind of between a rock and a hard place," Ciaccia said of the manufacturers. Many have made lower-cost versions of their products available, but those don't get listed on the formularies because they don't offer any rebates on them, he said.

Rebates are payments offered back to the PBMs in exchange for preferred placement on their formularies. If the list price is $400 for an insulin product, the manufacturer may make $100 and give the other $300 back to the PBM, which typically passes those savings to its clients – employer and commercial health plans.

Patients may be forced to pay that $400 list price when they are in their deductible phase and don’t get any of that rebated money directly.

The government report found that manufacturers offered higher and higher rebates each year, in fear of being kicked off the preferred formularies. That means they must also inflate the list price each year to keep pace.

In July 2013, insulin maker Sanofi offered rebates of 2% to 4% of the list price – also called the wholesale acquisition cost or WAC – for preferred placement on CVS Caremark’s formulary, the finance committee found. Five years later, Sanofi rebates were as high as 56%.

Critics of the rebate system say it amounts to legalized kickbacks. In 2019, a class-action lawsuit accused manufacturers and PBMs of engaging in a commercial bribery "scheme," conspiring to raise the prices of insulin drugs to increase the fees manufacturers paid to PBMs.

Frazzled workers, temporary closures: How staff shortages and vaccine demand squeeze US pharmacies

CVS to close 900 stores: Drugstore chain's closings represent 10% of locations

Pharmacy benefit managers say the manufacturers drive up prices and keep out any competition from generics.

"Insulin pricing strategies used by drug manufacturers to avoid competition through ongoing patent extensions on insulin products are a significant barrier to getting costs down," said Greg Lopes, spokesman for the Pharmaceutical Care Management Association, which represents PBMs.

"PBMs have introduced programs to cap, or outright eliminate, out-of-pocket costs on insulin, and PBMs have stepped up efforts to help patients living with diabetes by providing clinical support and education, which result in better medication adherence and improve health outcomes," Lopes said.

Manufacturers, PBMs and nonprofits have set up patient assistance and coupon programs to reduce what patients spend on insulin. Each program has its own requirements to qualify, its own rules and restrictions, and patients have to be aware that the programs exist.

Drugmakers often advertise their patient assistance programs, but the onus ultimately lies with the patient to find and apply for free or reduced-cost insulin. Numerous organizations have developed databases of assistance programs to help patients navigate the sea of options, including PhRMA’s Medicine Assistance Tool, RxAssist, NeedyMeds and Beyond Type1's GetInsulin.org.

"For the population that can take advantage of those programs, that's great," said American Diabetes Association Chief Advocacy Officer Lisa Murdock. "We think insulin should be affordable at the point of sale for everyone."

Lopes pointed out that PBMs pass through to health plan sponsors the vast amount of the rebates they negotiate. In the case of Medicare Part D, the PCMA said that amount is 99.6%.

"The rebates are then used to lower premiums and out-of-pocket costs for patients," Lopes said.

Consumers can pay hundreds more under rebate system

Nonprofit drug price research group 46brooklyn released a report demonstrating how patients end up paying more because of rebates.

It looked at a box of Lantus insulin pens – which hold pre-dosed cartridges for easier injection – with a list price of $425. According to the Finance Committee's report, Lantus offered the PBM OptumRx a rebate of 79.76% or $339 in 2019.

The consumer's health plan gets that rebate every month regardless of whether the consumer pays full-price in the deductible phase or pays a smaller co-insurance amount later in the year.

46brooklyn used a fictional consumer who has a deductible of $1,644 – a figure the Kaiser Family Foundation says is the U.S. average.

Each month, January through April, the consumer in this scenario would pay close to the full list price for insulin, $408 in this case based on retail price data. Those same months, the health plan, paying $0 toward the insulin, would receive a $339 rebate. The manufacturer of the insulin would get the difference, or $69 in this scenario.

Walmart insulin: Walmart launches its own low-cost insulin to 'revolutionize' affordability for diabetics

The rest of the year, once the consumer hit his deductible, he would pay about $34 for insulin each month. The health plan, after rebates, would pay about $35, giving the manufacturer the same total of $69.

At the end of the year, this fictional diabetic spent a total of $1,906 for insulin while the manufacturer made $828. The consumer's health plan via the PBM came out ahead, profiting $1,078 after getting more than $4,000 worth of rebates.

If all the middlemen and insurance were cut out, and the consumer was simply charged the net cost of the drug every month, 46brooklyn argued, the consumer would save more than $1,000 a year while the manufacturer would make the same profit.

A study by researchers at the University of Southern California found that manufacturers, often blamed for rising prices, actually make less money as list prices rise. Since 2014, while list prices rose by 40%, the net price that manufacturers made off their insulin products decreased more than 30%, according to the study published in JAMA Health Forum.

The PCMA disputed the accuracy of 46brooklyn's rebate scenario.

"By cherry picking an extreme and unrealistic example of high patient out-of-pocket costs, the 46brooklyn report does a poor job of depicting the health care experience for most insured people with diabetes," Lopes said. "For example, the report’s out-of-pocket cost assumption is actually significantly higher than the amount at which many plans set or cap patient cost sharing for insulin."

There are consumers who reported paying $400 out-of-pocket for a month's supply of insulin after insurance. Rod Regalado is one of them.

A father's crusade

Regalado had never heard of a pharmacy benefit manager before two years ago.

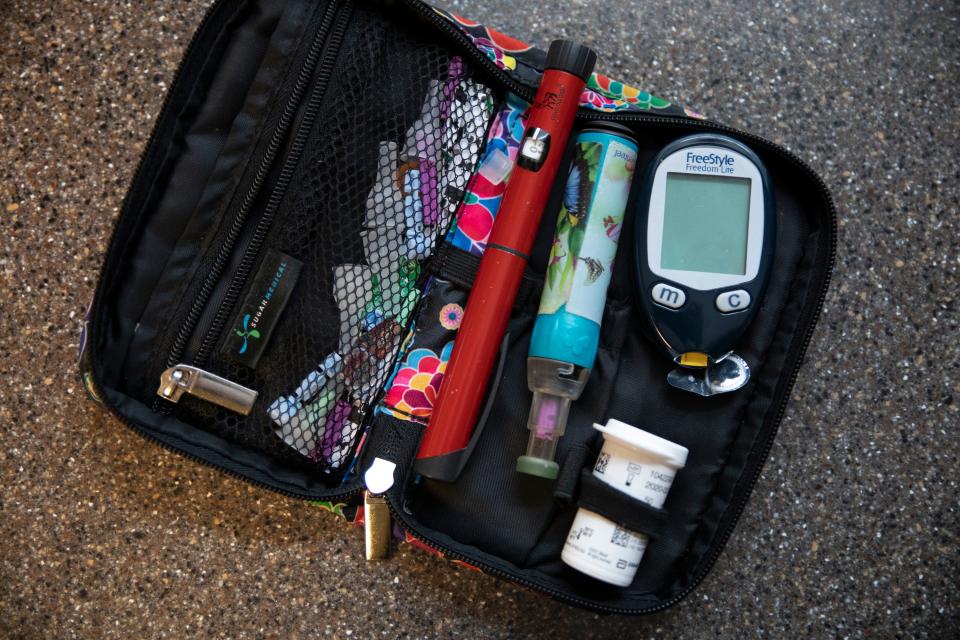

That’s when his son Matt, then 14, was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes and Regalado got a crash course in insulin pricing.

His first trip to the pharmacy when his son was released from a hospital came with a $1,000 price tag for all the testing supplies and insulin he’d never purchased before. The next month, when all he had to do was buy more insulin, the price was still north of $400 after insurance.

The single dad of two said he thought he had good insurance until he found himself having to redo his entire household budget to afford insulin.

“I thought how do people do this?” he said.

The resident of Tekamah, Nebraska, started making calls to his insurance, pharmacy and doctors, trying to figure out a way to lower his out-of-pocket costs. Then he called his congressman.

“The harsh reality is that the cost of insulin is artificially high and ever-escalating,” U.S. Rep. Jeff Fortenberry, R-Neb., said in July when he and Rep. Angie Craig, D-Minn., reintroduced their bill aimed at capping prices. “Matt’s Act makes insulin prices fair for everyone by capping the price at $60 a vial and $20 a vial for those on insurance.”

Though legislative efforts have focused on capping out-of-pocket costs, there has been a push to eliminate rebates altogether and drive down list prices across the market. That would require the buy-in of all parts of the drug supply chain.

Some PBMs have created formularies that don't require rebates, but they struggle to get health plans to adopt them. The insurers have come to expect and rely on the money from rebates, and some have them written into their PBM contracts.

'A momentous day'

Ciaccia of 46brooklyn pointed to the new insulin product Semglee as an example of how dysfunctional the marketplace can be.

In July, the FDA approved Semglee as the first interchangeable biosimilar insulin product. Biosimilars are like generic drugs in that they can be substituted at the pharmacy counter without needing a separate prescription.

Semglee is interchangeable with Lantus.

More biosimilars are likely to gain approval in the next few years. They’ve been touted as game changers that will lead to lower prices and more options for patients.

Acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock called it “a momentous day” for people who depend on insulin. “Biosimilar and interchangeable biosimilar products have the potential to greatly reduce health care costs,” she said.

Biocon and Viatris, the makers of Semglee, launched two different versions of the drug – the branded one called Semglee and a nonbranded version called insulin glargine.

The nonbranded version’s list price is about $148 for a package of five 3-ml pens, which is 65% cheaper than Lantus.

There is indication that the largest PBMs in the country won’t carry that version on their preferred drug formularies, instead offering the branded Semglee, which has a reported list price of $404 per package of five. That makes it only slightly cheaper than Lantus at $425.

Any patients whose health plans use Express Scripts' National Preferred Formulary for pharmacy benefit management will not have access to the much cheaper nonbranded option. Only the more expensive Semglee is on that list for 2022.

Why would the cheapest possible option not be offered by a health plan?

PBMs such as Express Scripts make money from administrative fees that are calculated as a percentage of the list price. The higher the list price, the more money they make. Health insurers, including employers, generally get to keep most of the rebates offered by manufacturers, which are also higher when the list price is higher.

“Consequently, many commercial payers will adopt the more expensive product instead of the identical – but cheaper – version,” Drug Channels Institute CEO Adam Fein said in a blog post about Semglee. “As usual, patients will be the ultimate victims of our current drug pricing system.”

Asked about the Semglee formulary decisions, an Express Scripts spokesman said the lower cost insulin glargine is included on the PBM's Flex Formulary. He did not answer how many of Express Scripts' customers choose that formulary over the National Preferred list. Consumers have no say in what formulary their employer or health plan chooses, and Fein pointed out that many choose the preferred lists that come with more rebates.

"As we do with all medicines newly approved by the FDA, Express Scripts evaluated Semglee and Insulin Glargine to determine formulary placement," a statement from Express Scripts said. "The placement of both medicines was based on the lowest possible net cost for clients that use those formularies and will result in decreases in customer out-of-pocket costs across all plan designs, an estimated $20 million in savings in 2022 alone."

Follow Katie Wedell on Twitter: @KatieWedell and Facebook: facebook.com/ByKatieWedell

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Insulin prices stay high as rebates drive up costs for diabetics