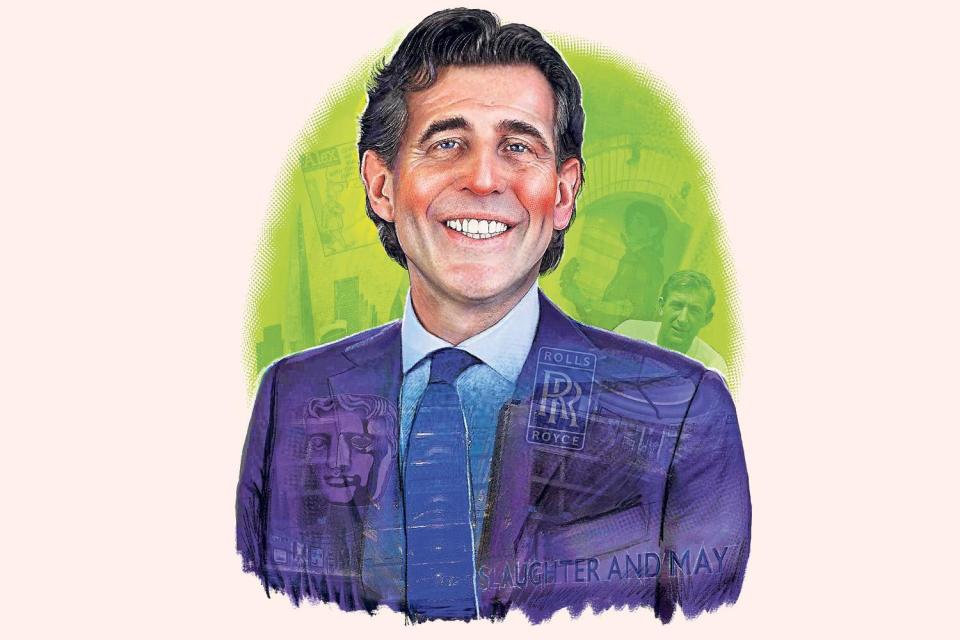

Meet Steve Cooke: The Slaughter and May lawyer smashing stereotypes with scores of success

The Groucho Club. Famed the world over as the Soho haunt of A-listers: actors, musicians, agents and… corporate lawyers. Huh?

Yes, you read that right. When Steve Cooke, global boss of Slaughter & May invites me for a chat, it isn’t to a corner office high up a glass City tower, or even the pinstriped RAC on Pall Mall. No, for Cooke, “meet me at my club” means the Groucho.

For a man whose firm counts a third of the FTSE-100 Index as a client, and has worked on several of the most high profile corporate investigations and deals in recent years (SFO v Rolls-Royce, Ocado and Marks & Spencer), this is hardly what you’d expect.

There’s a lot you wouldn’t expect of Cooke. I’m here, for example, because he’s written an autobiography*. Unusual enough for a corporate lawyer schooled in the arts of keeping one’s counsel. And the reason he’s deemed himself worthy of such prose? His teenage years as a coulda-been-a-contender popstar.

Cooke’s post-punk band, the Stereotypes, made it to daytime Radio 1 via the DJs John Peel and David “Kid” Jensen, but split, with no record deal, in 1980 while he was still at Oxford.

So it’s not for the Stereotypes that Cooke is a deserving member of the Groucho. He’s there because while not running the city’s most blueblooded law firm, he has a secret life making music for television and film documentaries. Rather successfully.

Every other Sunday evening he and an old college friend get together at Cooke’s home in Little Venice and record. They’ve done scores for Bafta and Emmy award winners and had their music mentioned in Bafta dispatches, even doing the music for the last David Attenborough film, the Queen’s Green Planet. In short, they’re pretty darn good.

“It’s a lot of fun. We’ve been doing it for decades now so it’s just part of my life: Sunday night is recording night,” he grins.

TV music has also helped secure him a romantic partner. His girlfriend is the undercover documentary maker Kate Blewett.

As if that’s not surprising enough, his musical co-performer is none other than Russell Taylor – one half of the Alex cartoon scribes Peattie and Taylor.

Slaughters’ clients can breathe easy. While Cooke says he gives the odd idea for a strip, Taylor says that’s rare: “We both have fairly high profile jobs in the City but in all these years, we only ever talk about music, really.”

The book’s a cheery romp from wet childhood holidays in Wales to his first round of law firm interviews in a cheap Mister Byrite suit.

It’s as much soundtrack as biography, referencing songs from The Clash to Prince as a Nick Hornby-like technique to keep the reader on track with the progressing dateline.

For anyone who grew up in the London ‘burbs in the sixties and seventies, it’ll have you pining for those days when your dad’s hi-fi was a slab of furniture the size of a Triumph Herald.

It’s full of photos of Cooke, but given it ends in 1980, I didn’t instantly recognise the 60-year-old in the club’s airy upstairs restaurant when I arrived. Then, sitting near a Cabinet minister huddled in the corner with a famous political journalist, I spot him.

The hair is still floppy, but expensively quaffed. He’s slim in a well cut suit and has one of those faces that improve with age.

In the book, he has something of the baby-faced Tory boy about him, even when leaping around the stage brandishing his Les Paul. Now, though, good cheekbones combine with eyes that drop, Brando-like, at the outsides. It’s his father’s look. Pictures of Cooke Pere in tux or World War II uniform show a spit for the dashing villain played by Billy Zane in Titanic.

Childhood for Cooke was in Hornchurch, Essex, where he inexcusably supported Spurs in a land of West Ham Claret and Blue. That despite his adored mother’s loathing for captain Danny Blanchflower (not the eccentric City economist).

No Essex in his voice now, though. It’s pure BBC, perhaps with a touch of the Smashy and Nicey DJ about it. What little music there was in the house was terrible: “I lived in a 1960s that sounded like it had been curated by Val Doonican,” he says. “We didn’t have The Beatles playing, we had Lennon and McCartney played by Alan Haven on the organ,” he grimaces. “It was horrible but you got to know the tunes.”

Eventually, he got to hear The Clash and his world changed. “Amazing band,” he says. “saw them three times in ’78 and they’re still my three favourite gigs of all time.”

Having got close, but not that close, to a proper record deal, he decided to put his law degree to good use. To his amazement, Slaughter & May picked him up after a good cop-bad cop interview where the bad cop – Michael Pescod – went on to be his boss, mentor and eventually a best friend. “Maybe because I had watched too much of the Sweeney, I preferred the bad cop,” he recalls.

After doing the rounds trialling property law, litigation, and then corporate and mergers and acquisitions, he fell for the charms of the latter. For the money, I presume? No, we’re a partnership, so that didn’t factor in. I liked the excitement of it. It was a bit seat-of-the-pants. Complicated. Intellectually challenging. You never knew what was going to happen next.”

Is there any crossover between his musical side and the law? He hesitates, dubiously, then: “Probably one of the reasons we get so much work in music is that I’m incredibly organised and never miss deadline. There are plenty of musicians out there who will send off that blank tape and then call in: ‘Did you get it? Oh, it’s blank. Really? OK give me a couple more weeks.”

Cooke’s dialogue constantly switches in and out of such imagined conversations for comic effect, a tic he shares identically with Taylor. In fact, but for Taylor’s less organised thoughts, you imagine they must be like an old married couple.

There are other musical crossovers with work, he says, particularly in the role that very senior legal advisers take on. “In law your core skill is to be logical but also at the higher end of lawyering, being creative is very underrated, I guess. Coming up with new ways of doing things, to find a solution nobody else has thought of. I guess that’s similar to creating a new piece of music in a way.”

He’s self-effacing in a very English way, underplaying how hard he must have worked at Oxford, or how stressful and driven he must be to run 1300 of the world’s top lawyers.

It’s an Englishness that I imagine goes down well in Slaughters, that most blue-blooded of firms.

For all the constant jokes, he’s also studiedly discreet, resolutely cutting dead any attempts to discuss clients: on, or off the record. That’s extremely annoying if you’re a journalist.

Perhaps it’s because Slaughters has trained him, when it comes to long-term issues such as reputation, to be risk averse. Slaughter is the only major firm which is still a general partnership; that old school structure wherein all assets, profits and – crucially – liabilities are shared equally among the partners. One of us screws up, and we all go down.

Is that why you don’t see so many dodgy Russian oligarchs on the books as some firms we could mention? “We are very conservative. We play a very long game and ask what would one of our more mainstream clients think about us taking on that client. That is quite a good test, really.”

The legal world is abuzz with law firms raising capital on the stock market or merging. Every week seems to bring a new flotation, with partners declaring they need to float to have more financial firepower, buy up smaller rivals and give sub-partner level staff shares in the business.

Cooke is far from convinced. “Law is not a massively capital intensive business. We have debt, but not a huge amount. What’s the real reason for these IPOs? To crystallise the goodwill of the partnership for the benefit of one generation of partners. You’re turning what is going to be an income stream for years into one payment. There’s an obvious temptation for existing partners to doing that, but…”

He trails off dismissively. It doesn’t sound like Slaughters is going that way any time soon.

Rumour has it that Wall Street investors have been trying to create a sort of fund-of-fund of law firms. In return for, say 10% of your firm’s earnings, you get to share the profits from a large group of top tier firms. I pose the idea to Cooke, but he shakes his head: “Interesting to hear, but not for us,” he says.

For 130 years, Slaughter and May has always been a partnership, has never bought another firm and only ever hired one partner from outside the firm. “Maybe we’ll hire another in 130 years,” Cooke grins.

It’s an odd contradiction, from anarchic popster to the City. There was one guy who tried it the other way, and he was a regular visitor to the Tory flat below his in Cooke’s final year: Guy Hands. Hands made a fortune in finance before his love of music got the better of him and he bought EMI. Even Hands admits the spectacular failure left him looking a “chump”.

No such slips for Cooke, so far.

He clearly loves his work, having the ear of the country’s top chief executives and chairmen.

And though boardroom life may be a far cry from the rock star world he’d dreamt of at 18, the Stereotypes’ most successful track still resonates. Its title: Calling all the shots.

*The Morning Of Our Lives is a available on Amazon