If Dr. King Came Back Today, He'd Be Heartbroken—and Energized

When the rest of America is celebrating Martin Luther King Jr. Day on Monday, Alabama and Mississippi are observing a different holiday: Martin Luther King Jr./Robert E. Lee Day. And for a while, those states weren’t alone-Arkansas ended its joint holiday little more than a year ago. Bundling a holiday celebrating our nation’s most beloved civil rights leader with one for a man who fought to maintain slavery is one of the purest indications that our nation hasn’t truly reckoned with its history, so I talked to someone who is: lawyer, activist, and MacArthur “genius” Bryan Stevenson.

Stevenson is the founder of the Montgomery, Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative. The EJI guarantees legal representation to anyone facing the death penalty in Alabama, and has saved 125 people from execution. Stevenson successfully argued the unconstitutionality of imposing mandatory life sentences on juvenile offenders before the Supreme Court, and with the EJI founded the country’s first national lynching memorial, as well as a museum dedicated to the history of slavery of and Jim Crow. His extensive and inspiring resume suggests that Stevenson is one of the living activists whose work most embodies Dr. King’s legacy.

Stevenson frequently mentions the fact that Alabama co-celebrates King and Lee in interviews, invoking it as an illustration of America’s misguided approach to racial reconciliation. Almost half of the union was pointedly late when it came to honoring Dr. King-while Ronald Reagan signed the bill marking his birthday as a federal holiday into law in 1983, only 27 states initially observed it. Many politicians who voted against the holiday’s creation remain familiar names today, including Iowa senator Chuck Grassley, former Utah senator Orrin Hatch, and late Arizona senator John McCain. Over the years most states came into the fold, with New Hampshire becoming the final state to adopt the holiday in 1999.

Some southern states, however, were reluctant to concede defeat, and decided to bundle King’s birthday, January 15th, with a holiday they already celebrated-the January 19th anniversary of Robert E. Lee’s birth. In recent years these joint holidays have been largely dismantled in the South, though confederate holidays persist even in states than honor King alone today. And in Alabama, MLK/Lee day isn’t the only Confederate occasion on the calendar-the state also observes Confederate Memorial Day and Jefferson Davis’s birthday. I talked to Stevenson about the the joint holiday, America’s struggle to reckon with its past, and the legacy of Dr. King.

Are most people in Alabama aware of the fact that the holiday is officially Martin Luther King/Robert E. Lee day?

I think people were aware of it when the holiday was created. We still have a sort of segregationist mindset in the American South-I think the idea was that a holiday for Martin Luther King was going to be for black people, and therefore, having Robert E. Lee Day would be something for white people.

I think there was this sense in which we haven’t really thought about the legacy of Dr. King as a legacy aimed at helping everybody. If you’re a community that believes that white people are better than black people, that black and white people shouldn't go to the same churches, or the same schools, or drink from the same fountains, Dr. King’s view was that makes all of you burdened. It’s not just black people who are burdened with segregation, it does something corruptive to white people, too. That he came along and led a movement that ended the legal architecture of racial segregation is something we should all celebrate. It’s certainly my view that Alabama is a better place without a legal landscape that requires racial segregation. And I think Alabama and Auburn college football fans would agree with that.

And so I think people do know that it’s Martin Luther King/Robert E. Lee Day. I just don’t think they’re terribly troubled by that. Alabama’s one of the states where we still have a romantic, celebratory mindset when it comes to our nineteenth century history. Confederate Memorial Day is a state holiday as well. Jefferson Davis’s birthday is a state holiday. And I think this effort to characterize what happened in the 19th century as somehow noble and worthy of honor and celebration is a remnant of the kind of misguided history that we have to overcome if we’re going to actually create a healthier community.

You’ve mentioned that Alabamians root for racially integrated football teams while school segregation is still technically state law. How do you think people deal with that contradiction?

I think people have been told that nothing shameful ever happened in Alabama, and that what happened in the past was not a function of bad behavior or lack of character. It was just a sign of the times, just the way it was. And because we haven’t created a consciousness of shame or regret or remorse about enslavement, or convict leasing, or lynching, or segregation, we haven’t been motivated to create new narratives about how we deal with that.

In Germany, there are no Adolf Hitler statues. People are not trying to erect monuments and memorials to the architects of Nazism and fascism. I think there’s a recognition that what happened during that era was not just wrong, but shamefully destructive, and that society has made a commitment to overcoming that history. That’s why they banned swastikas.

Well, we haven’t done that in America. And that has allowed people to be comfortable with embracing, even celebrating the architects and defenders of slavery and this history of racial inequality, while still trying to benefit from all of the positive consequences of integration on a college football team, in entertainment, and in all the areas where the state feels like there’s something to be gained.

And so I really believe that we haven’t done the kind of work we need to do to get people to appreciate the harm that is done when you, say, vote to maintain the language in the state constitution that still prohibits black and white kids from going to school together, which voters in Alabama have done twice in the last fifteen years. In 2004 and in 2012, the majority of voters in this state ratified the language that prohibits racial integration in public schools. It’s completely unenforceable under federal law, but a majority elected to keep that language in the state constitution.

Because we haven’t made it consequential for people to engage in this kind of romantic worldview around this history, people haven’t been motivated to see the harm. And that’s why articulating the harm, the damage, and the pain, agony and anguish created by slavery and by lynching and by segregation is so urgent and so important.

There’s post-World War II footage of occupying allied troops literally forcing German civilians to view the Nazi destruction. Civilians were marched into former concentration camps and made to see what happened there. Without a similar kind of forced reckoning, do you think it’s possible for us to achieve what Germany has?

I definitely think it will be harder. Because you’re right-Germany lost the war. And if Germany had won, you likely wouldn’t have Holocaust memorials and the consciousness that we see today. The same could be said about South Africa. A black majority took power, which opened a door for an Apartheid Museum and a Truth and Reconciliation process. In Rwanda, the victims of the genocide ultimately reclaimed power.

What we’re trying to do in the United States is much harder in that there has never been a transfer of power. The perpetrators of the violence-those who were beneficiaries of white supremacy-never lost. And you can even argue that the North won the Civil War but the South won the narrative war. The idea of white supremacy not only survived but thrived after the Civil War. So yes, our work is harder. We can’t force that reckoning, but I think we can create a new environment, a new landscape.

When I moved to Montgomery in the ‘80s, there were 59 markers and monuments to the confederacy. You couldn’t find the word “slave” or “slavery” or “enslavement” anywhere in this city, even though we were one of the most active slave trading spaces in America.

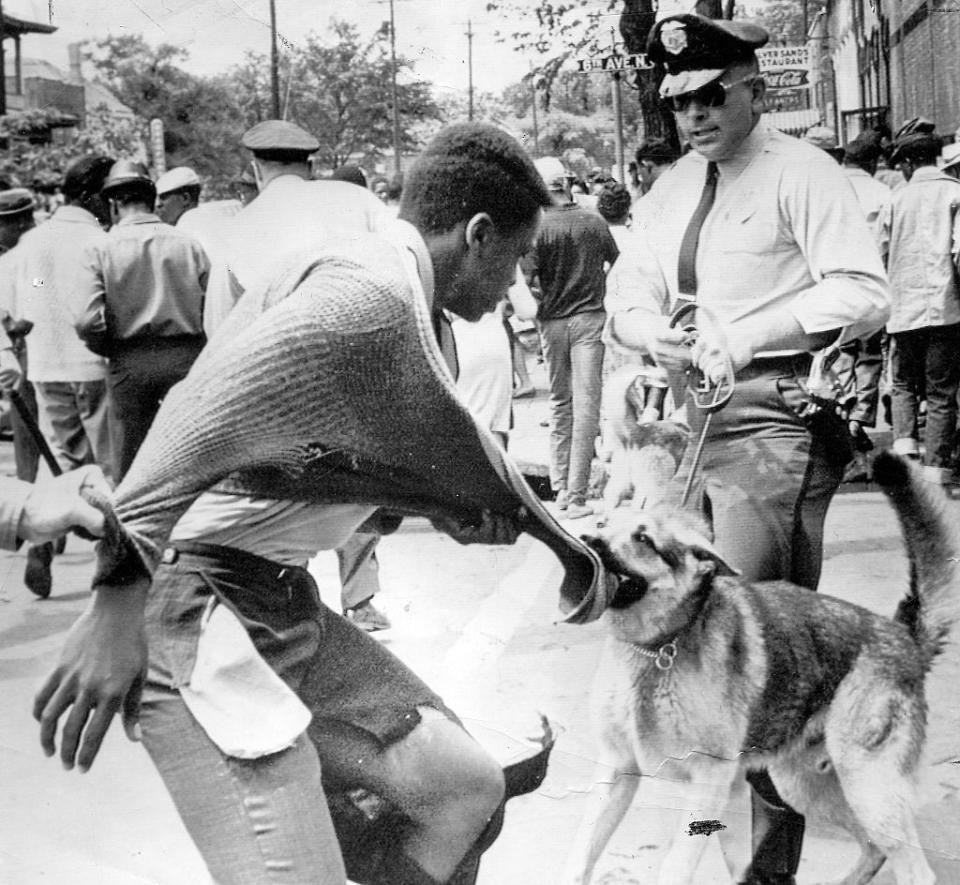

We have been practicing silence about this history. And that has to change. We now have markers up that talk about the slave trade, we’ve now opened a museum, From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, we’ve created a memorial about the history of lynching, we’re putting up markers and landmarks that educate people about some of the terrible violence and terrorism that took place, sometimes literally on the courthouse lawn.

If we do that effectively, we will provoke a conversation that will make people engage in some of the reckoning that the allies forced on Germany at the end of World War II. It will take longer, it will be harder, but I actually believe that there is a power in the truth about enslavement, lynching, and the humiliation of segregation, that will make it difficult for people to avoid once they confront it. People born in America in the 21st century who learn this history will have a hard time celebrating the people who perpetuated the kinds of violence and bigotry and cruelty that defined that era of American history.

Even in parts of the country that don’t actively celebrate the confederacy, MLK day is often treated as a celebration of the end of race hate, as if racism is entirely in the past. In what ways can we change that narrative?

I think you’re right, I think we’ve gotten very celebratory when it comes to civil rights. And it’s almost as if we’re saying, “Well if we celebrate Dr. King’s birthday, then clearly we have eliminated racial bias.” And I think that’s part of why so much work needs to be done. I think rather than Dr. King’s birthday symbolizing some great success, we should see in his birthday a great challenge.

When Dr. King was assassinated, he was pushing this nation to do better when it came to militarism and when it came to confronting poverty. And he lost a lot of his allies and he was maligned and disfavored by so many people. He was in the midst of a new struggle when he was killed in 1968. And if we’re going to be honest and honorable about celebrating his life, then we have to be mindful of that struggle that still continues.

I believe that if Dr. King came back today, he would be heartbroken to know that one in three black male babies born in this country is expected to go to jail or prison, to know that 60 million people live beneath the federal poverty level, to see the levels of segregation that still persist in education and housing and employment-I think he would clearly say, “My dream has not been realized.”

But I also think that he would be energized by the possibilities of convening millions of people-professionals, writers, doctors, lawyers, teachers-and accessing the skills that could be accessed if we actually said, “We have to confront of racial injustice, we have to do better when it comes to overcoming our history of racial injustice.” That opportunity is rich and vital, and I think that’s what Dr. King’s birthday ought to stimulate-the call to action that he would surely make if he were here.

('You Might Also Like',)