Plea deal by Russian agent Maria Butina describes 2016 influence campaign

WASHINGTON — It was called the Diplomacy Project — an ambitious campaign to curry influence within the Republican Party and change its views toward Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

But the chief operative for the project, Maria Butina, a striking young woman from Siberia, was no diplomat. Instead, as she admitted in federal court Thursday, she was a covert agent of the Russian Federation dispatched to the United States by a senior Russian official to develop “unofficial channels of communication with Americans having power and influence over U.S. politics.” The goal: to change U.S. policy toward Russia, especially around the sanctions imposed after Moscow’s invasion and annexation of Crimea.

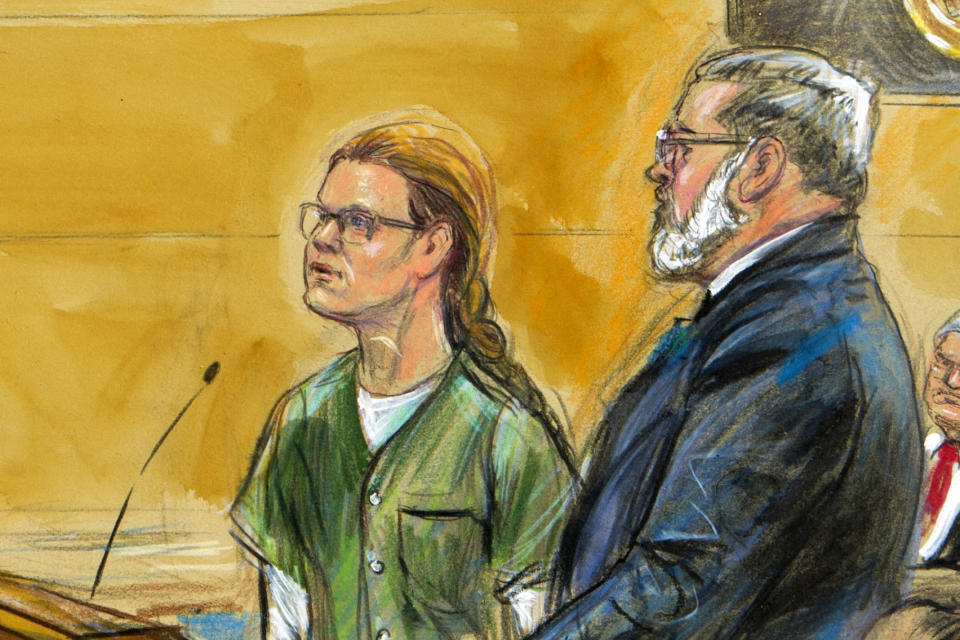

Butina, now 30, wearing glasses and a green prison suit and speaking in terse monosyllables, appeared before U.S. District Court Judge Tanya Chutkan. Looking chastened and anything but glamorous, she entered a plea of guilty to one count, not of espionage, but of failing to register with the Justice Department as an agent of a foreign government, a crime that could result in up to five years in prison. But Butina also has agreed to cooperate with federal investigators, marking another milestone in the investigations into Russian attempts to influence the 2016 election.

Butina’s case is not being prosecuted by special counsel Robert Mueller. Instead, for reasons that remain unclear, it was handed off to the U.S. attorney’s office in Washington. But it appears to have been a notable part of Russia’s political influence campaign in large part because of the creative means devised by Butina and her handler in Moscow, Alexander Torshin, a former deputy governor of Russia’s Central Bank and influential figure in Putin’s United Russia party.

As laid out by federal prosecutor Erik Kenerson, who dryly read a seven page “statement of offense,” Butina and Torshin concocted a plan to influence the GOP by cultivating relationships with the leaders of a “certain U.S. civil society gun rights organization” — a reference to the National Rifle Association. In a written proposal she drafted for Torshin in March 2015, titled “Description of the Diplomacy Project,” Butina predicted that the Republican Party candidate in 2016 would win the presidential election and she pointed to contacts she had made at NRA conventions as having “laid the groundwork for an unofficial channel of communication with the next U.S. administration.”

Butina wrote the Diplomacy Project paper with the assistance of somebody Kenerson described as “U.S. person 1” — a reference to Paul Erickson, a South Dakota conservative activist with whom she was having a romantic relationship. And, after her project was funded with $125,000 by an unidentified Russian billionaire, it brought a high profile delegation of NRA leaders to Moscow in December 2015 for meetings with high-level Russian government officials, sessions that were arranged by Torshin. After the meetings, Butina wrote a note to Torshin, referring to the NRA leaders that Kenerson told the judge has been translated two different ways. One translation was: “We should let them express their gratitude now, we will put pressure on them quietly later.” Another translation, a bit more subtle was, “We should allow them to express their gratitude now, and then quietly press.”

That was hardly Butina’s only endeavor as part of the Diplomacy Project. With the funds supplied by the Russian backer, she traveled the United States attending NRA conventions and other political events. One of them, not mentioned by Kenerson in his presentation in court, was a July 2015 event in Las Vegas, called FreedomFest, where she appeared in the audience during a talk by then candidate Donald Trump and asked him what his policy would be toward sanctions on Russia. Trump responded: “I believe I would get along very nicely with Putin, OK? I don’t think you’d need the sanctions.” It was the first time Trump had addressed the issue as a candidate and, thanks to Butina’s question, he had given the Kremlin exactly the answer it wanted.

Kenerson told the judge that Butina’s efforts to influence U.S. policy continued right through the 2016 campaign, including setting up “friendship dinners” with influential political figures, attending an NRA convention in Louisville, and organizing a Russian delegation to the National Prayer Breakfast in January 2017 with members “hand-picked” in consultation with Torshin to “establish a back channel of communication” to the new Trump administration. (President Trump was slated to meet with Torshin at the prayer breakfast, but when National Security Council officials got wind of it, they scrapped the meeting.)

The statement of offense that Butina pleaded to leaves open the possibility that her cooperation will lead to charges against other figures. But it says nothing about what many investigators had suspected — that Russian money might have been funneled into the NRA as part of its unprecedented $30 million expenditure during the 2016 election on behalf of Trump’s candidacy. That could mean Butina has more information to provide or, alternatively, that her efforts — while provocative and secret — were not quite what investigators in the FBI and Congress had suspected.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Cohen is a ‘serial liar,’ says former Trump aide Lewandowski

Take a number: Migrants, blocked at the border, wait their turn to apply for asylum

An American killing: Why did the U.S. Park Police fatally shoot Bijan Ghaisar?

I called George Bush a ‘wimp’ on the cover of Newsweek. Why I was wrong.

Photos: Manhunt for Strasbourg, France, Christmas market attack suspect