How Red Bull Pissed Off a Generation of Athletes

Phil Giebler is 40, now a graybeard—literally—wise in the ways of professional motorsport. Two decades ago, he moved to Europe to chase the dream of racing in Formula 1. Later, after a brutal wreck during practice for the Indianapolis 500, he opened a kart shop in Southern California. A large photograph on the wall of his office shows him racing at Indy during happier times, en route to being named rookie of the year. Another poster-size photo captures him in an open-wheel car wearing dramatic red-white-and-blue livery at Zandvoort, where he became the first American to podium in the A1GP series. But there’s no image immortalizing what Giebler considers to be the greatest drive of his career.

It was late 2002. Thirteen of the most promising American youngbloods had been flown to southern France’s Circuit Paul Ricard for the inaugural Red Bull Driver Search. They’d spent two days pounding around the course in a desperate effort to prove they were worthy of one of four slots on the fast track to a Red Bull–backed ride in Formula 1. The shootout called for seven drivers to be eliminated in the first cut, and this was the final session before the ax fell. Although all the cars were supposedly equal, Giebler was assigned to a tired nag two seconds off pace. He begged Indy 500 winner Danny Sullivan, who was running the program, to put him in another car. Sullivan refused.

“So I thought, I have to pull one out of my ass,” Giebler tells me. “It was all on the line. I wanted to do F1 with every cell in my body. Not having any money or much support financially, this was the holy grail—a chance to have everything I’d been lacking my whole racing career. I went out and laid down the laps of my life. I just nailed it. I was at least a second faster than anybody else in that car—maybe 1.2 seconds or 1.4. When I saw where I was [on the time chart], I was like, f*** yes! They put us all in a sealed-off room before our private interviews with the judges. All the other drivers were high-fiving me. I remember Bobby Wilson saying, ‘That was badass.’ So I felt really good. I knew there was no way they could dismiss what I just did.”

There’s a pause.

“I was totally relaxed when I went into the room for my interview,” he says. “Danny said, ‘Sorry, but you’re not going to the next round.’ I’m like, ‘Yeah, right.’ I’m looking around. ‘It’s a joke, right?’ ‘No, you’re not going to the next round. You’re not advancing.’ I went numb and must’ve turned whitish-green. I asked them, ‘Can you tell me one thing that I could have done better—just one thing?’ Danny said, ‘Well, for the experience you had, we think you should have been a little bit quicker.’ That’s when I started to get angry. I said, ‘You could put Michael Schumacher in that car, and he couldn’t go any faster than I did. There is nothing left in that car. Nothing!”

We’re sitting in Giebler’s California office, but he’s back in that interview room at Paul Ricard. His voice, which had been flat and matter-of-fact, turns almost raspy, and I can see his eyes glistening over at the unfairness of it all. “They told me, ‘Well, you’re one of the older guys, and we thought you should have been more of a leader and helped the other drivers.’ Helped them? Why would I have helped anybody? I would have given my left nut for that thing. I’d sacrificed everything to chase this dream.” He dredges up a sickly smile. “So, yeah, it was a huge letdown.”

The Red Bull Driver Search wasn’t the first talent quest of its kind, nor was it the biggest. But it was the most elaborate and expensive, and it generated the most buzz. It became a template for how to stage a motorsport gong show and a cautionary tale about the flaws of the selection process. “I was jaded, because I’d already gone through multiple driver shootouts where I was the fastest guy and I didn’t get picked,” says Rocky Moran Jr. “So I knew going in that it was somewhat of a cosmic lottery.”

Technically, the first search produced four winners, but only one grabbed the brass ring—Scott Speed, who spent a season and a half in F1 before being replaced by Sebastian Vettel. Speed then raced for nearly a decade in NASCAR before winning four consecutive rallycross championships as a factory driver. Once abrasive and arrogant, Speed has matured into a thoughtful professional. To him, the program was a lifeline thrown to a drowning man.

“Basically, the end of my career was very well in sight because I didn’t have any money to do anything,” he says. “I’d literally just signed up for community college. People have to understand that if it wasn’t for that program—100 percent if it wasn’t for that program—I would be working some shitty job. Only because of those people am I here today. It didn’t matter how much I wanted it or how good I was, none of it would have happened without them.”

The driver search was the brainchild of Maria Jannace. An enterprising New York City advertising/marketing maven, she put together an ambitious plan for a five-year program to identify young Americans who could be groomed to race in Formula 1. She spent seven years shopping the proposal to American companies. None bit. Then F1 driver Mika Salo suggested that she pitch Red Bull, an Austrian energy-drink company that had embarked on an unconventional marketing strategy built around an organic association with extreme sports.

Red Bull founder Dietrich Mateschitz already owned a stake in the Sauber F1 team and was eager to use motorsport to cement the company’s foothold in North America. But there was a problem.

“Our analysis was that there was no interest in Formula 1 in the United States because there were no Americans racing,” says Thomas Ueberall, Mateschitz’s longtime right-hand man. “Mr. Mateschitz always had an idea of an all-American Formula 1 team, and an American driver was the first step. We had to find a kid at a young age and then support him to learn the job of being an open-wheel racer in Europe.”

That’s why Mateschitz listened when Jannace cold-called him. “I knew I had all of about 30 seconds before he hung up on me,” she recalls. “But I was prepared, he was intrigued, and he flew over to New York. The deal was done within an hour of meeting, and he never compromised the program as I designed it.”

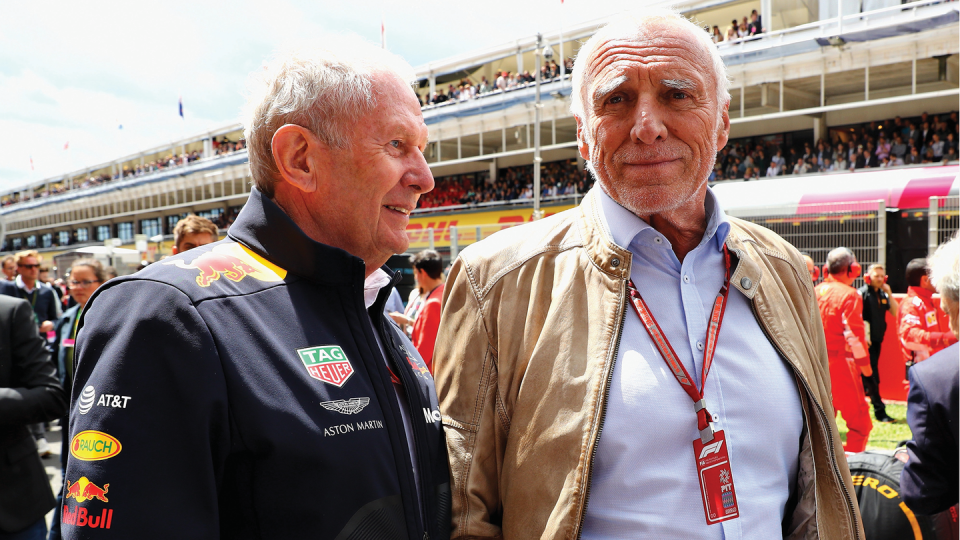

Sullivan, an ex-F1 driver renowned for his spin-and-win exploits at Indy, was hired as the face of the program, along with judges Skip Barber, Alan Docking, Bertram Schäfer, and the intimidating Helmut Marko, who would serve as Mateschitz’s representative. Sullivan and Jannace enlisted a wide array of scouts to identify candidates. Sixteen drivers were selected. Half were no-brainers. Giebler, Patrick Long, and Paul Edwards had already raced formula cars in Europe. A. J. Allmendinger and Bryan Sellers had won the Team USA Scholarship and proved themselves in New Zealand. Moran, Joey Hand, and Ryan Hunter-Reay were competing in Toyota Atlantics, one rung down the ladder from Indy cars. All could have been selected simply on the basis of their pedigree.

The other choices were more speculative. Speed was fast but raw. Mike Abbate was a 16-year-old karter. Grant Maiman, Joel Nelson, Scott Poirier, and Wilson had limited experience, mostly at the entry level. Bobby East and Boston Reid were oval-track guys adept in midgets and sprint cars. But young or old, most of them had absorbed the dirty little secret of career development—that without the financial support of a sugar daddy or a corporate sponsor, they had virtually no chance of making it to Formula 1. Suddenly, miraculously, here was a road map to the Promised Land. “It seemed like the break that everybody had hoped for but wondered if it would ever come,” Long says. “Not only was it the potential amount of funding that Red Bull was offering, but it was all the right players.”

The Red Bull Class of 2002 debuted at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway during the U.S. Grand Prix weekend. The timing was propitious. F1 was regaining traction in the United States, thanks to the series’ return to the country. The drivers paraded through the F1 paddock with a film crew in tow. Long and Hunter-Reay were interviewed live during the global TV feed. Later, more than 270 journalists—which Jannace says was an Indianapolis record—convened for the driver-search press conference.

The junket to Indy was a fantasy brought improbably to life. But along with the glamour came the first hint that this was the real world, with all its messy complications. The welcome packet that the drivers found in their hotel rooms included a thick legal document detailing their financial relationship with Red Bull. “It was this really crude, clumsy, and egregiously predatory contract that was basically indentured servitude,” Nelson says.

Allmendinger and Hunter-Reay, who already had rides for the next year, bailed almost immediately. East decided that his midget expertise was a bad fit for F1. Everybody else stayed on. “The contract was crazy,” Speed says. “But at the end of the day, I had no choice. I didn’t even think about it. They could have told me, ‘We’re going to pay you to go race in Europe, and then we own 80 percent of your all-time winnings from motor racing,’ and I would have been, ‘Cool, where do I sign?’”

Someone had thrown Speed a lifeline. You think he wasn’t going to take it?

The Red Bull circus arrived at Circuit Paul Ricard in southern France three weeks after Indy. The drivers had already gone through several group activities back in the States, so the atmosphere among them was reasonably easygoing. Until they met Marko. A Le Mans winner whose career had ended when a rock pierced his visor during the 1972 French Grand Prix, Marko was known for being notoriously demanding and ill-tempered. His forbidding presence was a tangible reminder that this was a win-or-go-home cage match among 13 supremely combative athletes fueled by an abundant supply of ego, ambition, testosterone, adrenaline, and Red Bull.

An analytical guy, Nelson made a conscious decision to keep to himself. “I didn’t socialize with anybody,” he says. “For me, this was it. There was nobody who was going to pay for my racing in the future, so I took it very seriously. I would either talk with Danny or Helmut Marko. I didn’t have anything to do with anyone else. I only wanted to know what the judges were looking for and to adjust my performance if necessary.”

Yahoo Autos

Yahoo Autos