Scientists Are Hell-Bent on Resurrecting the Tasmanian Tiger. Here’s Their Complicated Plan

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

De-extinction efforts focus on reviving extinct species or crafting new organisms that resemble said species—in this case, the thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger.

Colossal Biosciences in Dallas, Texas hopes to bring back the Tasmanian tiger with help from Australian scientists.

The plan? Finish genome sequencing before gene editing and engineering to birth a new thylacine.

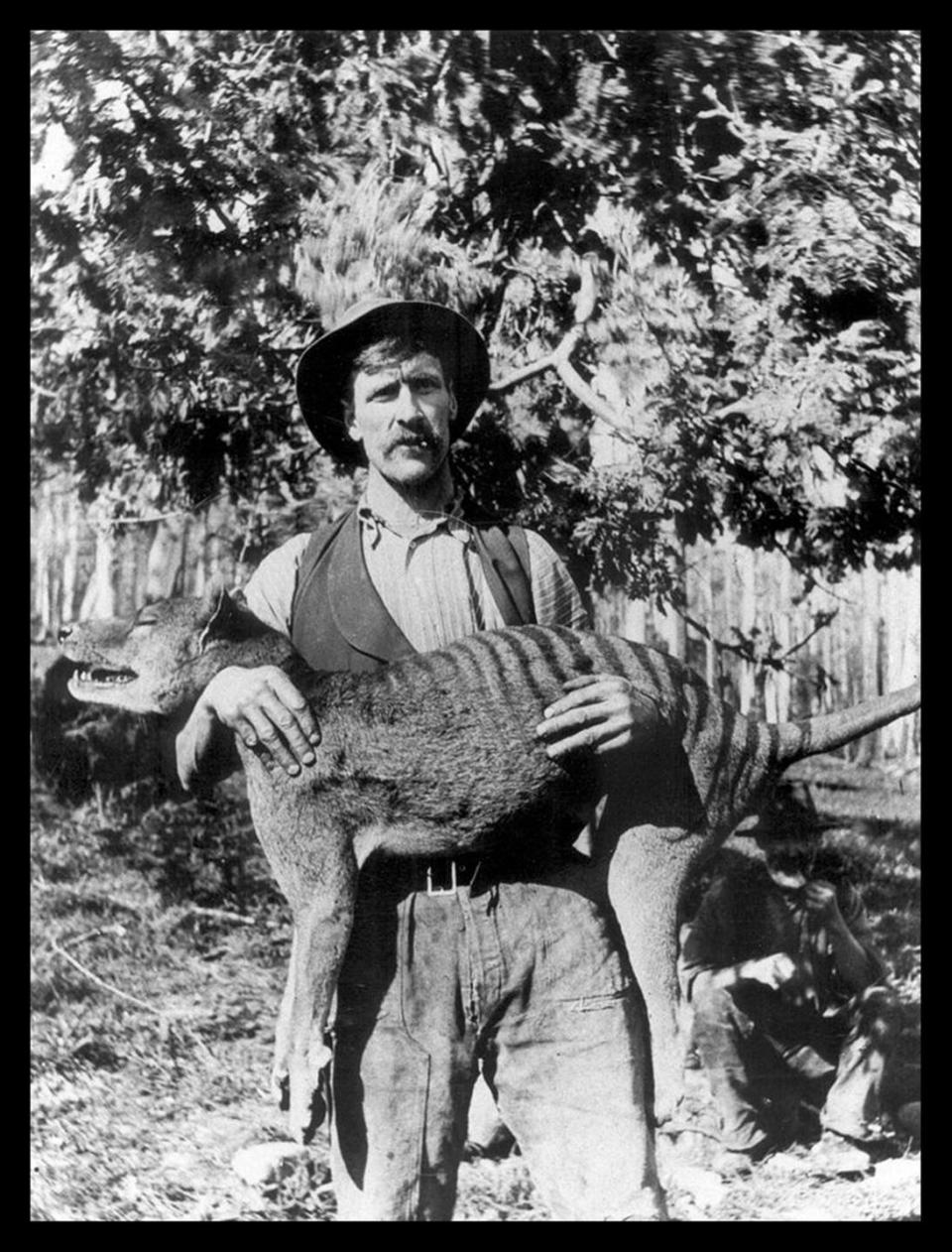

The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, roamed portions of southern Australia until settlers killed off the dog-sized marsupial carnivore. By 1936, the last of these creatures with distinctive tiger-like stripes on their backs died in captivity. But a Dallas, Texas-based company called Colossal Biosciences plans to bring the thylacine back to Australia through de-extinction, the (aspirational) process of birthing a new version of a lost species.

🦣 Science explains the world around us. We’ll help you make sense of it all. Join Pop Mech Pro.

On the heels of a September 2021 announcement, outlining plans to rebirth the woolly mammoth, Colossal Biosciences has partnered with an Australian scientist to work on the de-extinction of the Tasmanian tiger. “Combining the science of genetics with the business of discovery, we endeavor to jumpstart nature’s ancestral heartbeat,” the company says on its website.

Getting that ancestral heartbeat pumping again is no simple feat, though.

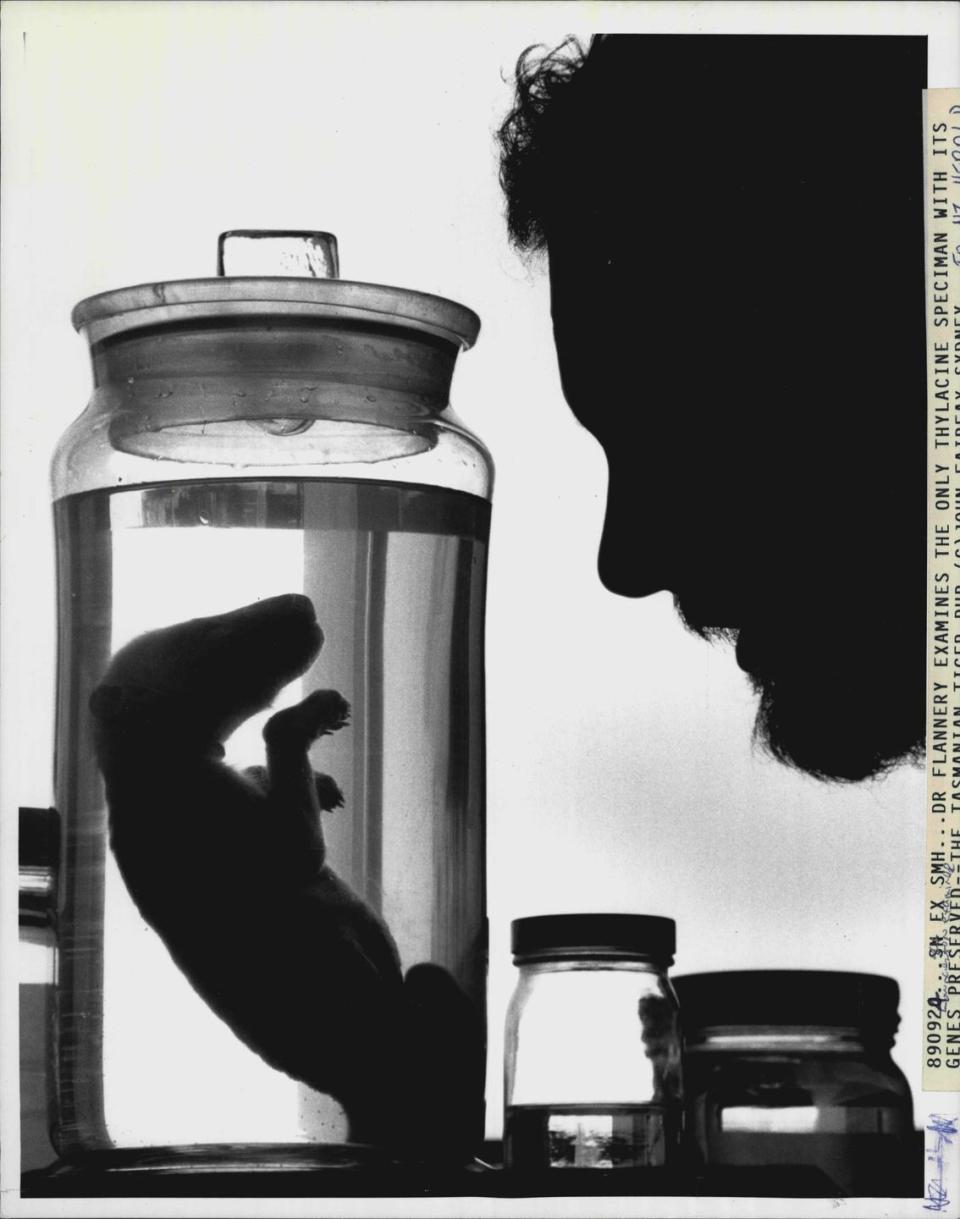

Colossal outlines a 10-step process for resurrecting the thylacine, from extinction to birth; that includes sequencing the creature’s genome through DNA extracted from a 108-year-old specimen preserved at the Victoria Museum in Australia. Andrew Pask, a professor of biosciences at the University of Melbourne and a member of the Colossal Scientific Advisory Board, will lead the charge on sequencing. As the foremost expert on the thylacine genome, he heads the university’s TIGGR Lab (Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research).

In 2018, Pask’s team published the first genome sequence of the thylacine. “While the draft assembly of the thylacine genome contained the overwhelming majority of its genetic information, we were unable to piece everything back together,” according to the TIGGR Lab website. Nailing that genome sequence will be the first monumental step in the process toward de-extinction.

If that pans out, bioengineering comes next. That includes everything from sequencing the thylacine’s closest living relatives, to computational biology to enhance a recipient host genome to be more thylacine-like, and establishing compatible cell lines for cell editing, sequencing, and stem-cell derivation.

Ultimately, this will lead to inserting thylacine genes into the genome of a dasyurid and stimulating embryonic growth until it is ready for a surrogate and eventual birth. The current plan calls for taking stem cells from the living dasyurid, or dunnart—a marsupial relative that bears basically no resemblance to the thylacine (think: mouse-like dunnart vs. wolf-like Tasmanian tiger)—and then editing genes to get as close to a new thylacine as possible.

Colossal expects this process to last a decade and Pask claims the first version will offer up a “de-extincted thylacine-ish thing” about 90 percent thylacine with the eventual goal to get to 99.9 percent, he tells Scientific American. In a Jurassic Park-like proposal, the engineered animals will live in their own enclosure with the continued goal of dropping the Tasmanian tiger back into the wild.

The thylacine started a steady decline when settlers started killing them off due to an incentive of a £1 bounty at the time (along with the help of dingoes). The thylacine was winnowed down to freedom only on the island of Tasmania, and a captive thylacine ended the species’ run after dying at the Hobart Zoo in 1936.

Not everyone believes this grand de-extinction plan is a sound judgement call. Since 1999, researchers have tried to sequence the genome of the Tasmanian tiger. It hasn’t worked. And even if it does pan out in the future, there are ethical questions about how to handle the creature, and if funding could’ve been better spent on conservation and protecting currently endangered species.

With Colossal already moving forward on the woolly mammoth effort—the genome of that animal is sequenced, and scientists will soon place it into the genome of the Asian elephant—the thylacine needs the final 4 percent of its genome sequenced before scientists can explore the possibility of using a dunnart genome for the next steps. Marsupials mark a relatively new world of research, so much of the plan has never before been done, and experts don’t believe the thylacine and dunnart are close enough to make it work.

Jeremy Austin from the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA tells the Sydney Morning Herald the entire plan is about media attention for the scientists. “De-extinction is a fairytale science,” he says. Only a new Tasmanian tiger (or something resembling it) could change that.

You Might Also Like