The Secret Tech Problem at Modern Art Museums

For the 100 years it’s been in operation, the Butler Institute of American Art in Youngstown, Ohio has been a repository for artwork by American masters, from preeminent 19th-century painters like Winslow Homer, to 20th-century realists like Edward Hopper and George Bellows, to pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein.

So in 2000, when the museum opened its Beecher Center for Electronic Arts-the first American museum dedicated solely to new media-it hoped to be a similar storehouse for modern artists. Among the works on display: holograms from Jonathan Ross, lightpaintings from Stephen Knapp, and a sculpture by Nam June Paik, considered by many to be the father of video art.

Paik, a Korean expatriate, found a home in the avant-garde New York art scene of the 1960s. He was one of the first artists to use a camcorder to capture videos and invented a synthesizer to alter them. His works incorporated television screens that showed everything from eggs to fish to the cello, and even built the stringed instrument out of television screens and recruited a musician to play it.

Paik can be found in the halls of the Smithsonian, the Whitney, and especially the Butler, where his “Ars Electronica” project (pictured below) once featured 20 Panasonic TV screens, each displaying everything from sitcom scenes to a blue background with black lines appearing intermittently.

But within a decade, a problem arose with the installation. One by one, the Panasonic screens started to burn out. The Butler was able to replace some of the 1993 cathode ray tubes through the miracle of eBay, but gradually those became harder to come by as well, and the museum was faced with a difficult decision: Do you put Paik’s piece into mothballs or upgrade his technology?

It wasn’t as if the museum staff could simply ask Paik what his vision was. He died in 2006-coincidentally, the same year Panasonic stopped making cathode ray tube televisions.

In the end, museum director Lou Zona decided to continue to show the piece. “We put flat screens inside the casings,” Zona says. “As a result, there’s no curve, so when you stand to the side, you don’t really appreciate what Nam June Paik did.” In fact, if you look at the artwork from the side, it becomes evident that the flat screens were retrofitted into convex cases.

Ars Electronica 2.0 may not have been exactly what Paik presented in 1994, says Zona, but the Butler tried to honor his vision as best as it could with the resources it had.

“Most modern art is born, it lives, and it passes on,” Zona says. “Museums try to keep artwork alive.”

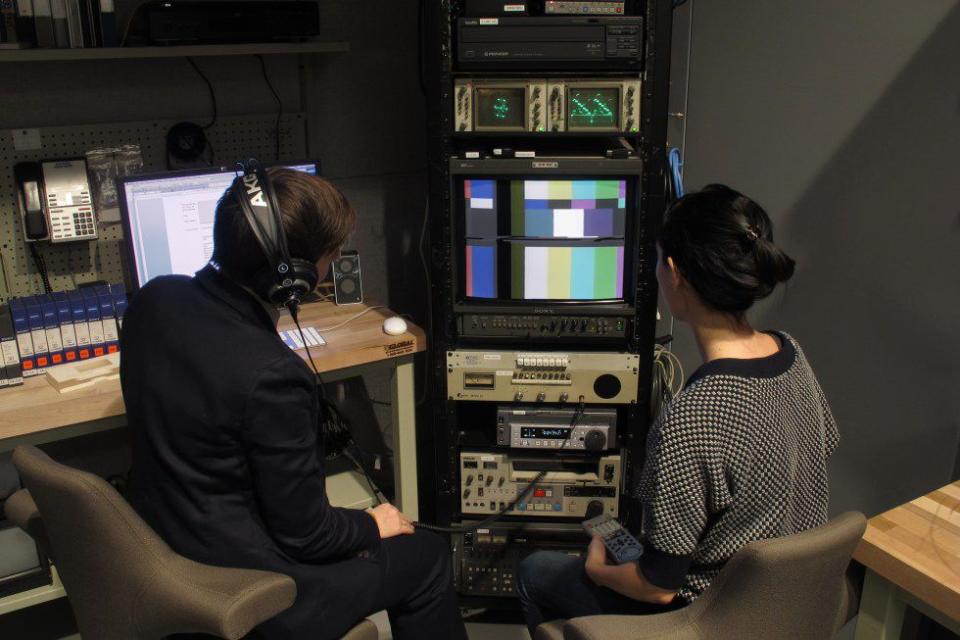

A Conservation Effort

Zona is well aware of the existential implications that come with trying to do that. He’s hardly alone. Over the past decade, the field of time-based media conservation has been growing-because it has to.

This year, two people will receive master’s degrees in the curriculum from New York University. It might not seem like much, but they’re the first with that type of specialization. Most time-based media conservators were trained in other media and ultimately fell into the field.

Glenn Wharton, for example, was trained as a sculpture conservator before moving into time-based media at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MOMA). He’s now the professor of museum studies at NYU.

“The first person was hired to do something like this in 2005,” Wharton says. “Now there are about a dozen. I think we need about 100. There’s a huge need, and it’s growing fast.”

Artists have always tried to work on the cutting edge. Sculptors moved from stone to clay to metal alloys, from bronze to steel to aluminum. Painters like Vincent Van Gogh used new and innovative pigments in their paintings; sadly, those face preservation issues of their own, as they’re prone to fading.

And when electronic and performing media came along in the 20th century, artists picked up new tools and toys, from moving pictures to recordable and replayable sound. Time-based media also has roots in the 20th century idea of kinetic sculptures-works with moving and potentially replaceable parts, exemplified by artists like Marcel Duchamp.

Time-based media refers to any work of art with duration, be it a five-minute video or a three-day piece of performance art, as opposed to traditional art like paintings or sculptures, which have physical, but not necessarily temporal, dimensions. This art also uses consumer products, and thus reflects the changes in those products, which can come quickly.

As magnetic tape became popular in home use, either for video or audio recording, it became popular for use by artists as well, Wharton says, as did the use of televisions. In 1950, 9 percent of American households had a TV set. Thirteen years later, less than 9 percent didn’t have one.

By the 1970s, artists were starting to gravitate from tape to computers, and as computer technology advanced, they jumped from formats like CDs and DVDs to flash drives and portable hard drives. While the 20th century progressed, Wharton says, these artists started to work more conceptually, also artistic heirs to Duchamp, who is regarded as the father of conceptual art. “The idea became more important than the object,” Wharton says.

As a result, some artwork is designed to be temporary-displayed for a short period and then thrown away. And the creators are just transmitting their work through the best possible media available at the time.

“Some artists say, ‘I don’t care about the nostalgia, just the image,’” Wharton says. “Can new technology express the work better?”

A Shifting Industry

It wasn’t until the 1990s that museums like the Butler started acquiring time-based works like those by Paik; Jenny Holzer, who used LED lights to offer social commentary; and Bill Viola, who gravitated from kinetic sculptures to visual art using video recordings.

The rise in time-based media had market influences, too, says J. Luca Ackerman, an associate conservator with the Better Image, a New York firm dedicated to photo conservation. Private collectors were taking an interest in time-based media-in some instances as a cheaper alternative to more traditional works.

“Time-based media is the new kid on the block, so there’s a cool factor,” he says. “But people who are entering the art world find it cheaper to get into.”

Ackerman notes that the ‘90s ushered in a migration from film to digital photos-not necessarily time-based media, but posing some of the same issues with preservation.

Ironically, Ackerman says, the migration was helped along not by the inability to find film for photography, but finding paper for prints. “Even 15 years ago, you could find 50 different types of black and white print paper in New York,” he says. “Now it’s down to about seven.”

Ackerman says more than 95 percent of photographers work digitally now, pushed into the medium first by the immolation of companies like Kodak and then by the ubiquity of smartphones.

“The art market started to accept digital prints as legitimate,” he says. “That was a signal to the rest of the art world that there’s a connoisseurship to it.”

But even now, time-based works aren’t collected as much, says Hannelore Roemich, a professor of conservation science at New York University.

“It’s still rather modest in price,” she says. “In a few years, museums will have more prominent time-based media collections.”

Pinning down a precise dollar amount, Roemich notes, is difficult. Most major auction houses don’t even have a category for time-based media, and if works change hands, they usually do so directly from galleries or the artists themselves-and then might not necessarily be publicly known.

As the 21st century dawned, time-based media started to have problems with its technology, as was the case at the Butler. Computers continued to offer new operating systems. The digital cameras that supplanted film were then supplanted by bigger cameras.

“There’s this misconception that all digital photo files are the same,” Ackerman says, “but digital photos could become archaic as file sizes get bigger. At some point, old digital photos won’t be usable. We’re constantly facing the idea of data migration.”

The changes are starting to come even more quickly now, says Roemich, as computers and cameras keep bringing out new models with improvements to gain market share-and indirectly, leave previous media behind.

“We’re always one step behind the artists, but we try to catch up,” she says. “Technology changes so quickly that even five years from now, we might not be able to save some artwork because the hardware or software has changed. We’re in a time machine. This is a current and accumulating problem. The urgency that we need to do something is less than 10 years old.”

A Safe Repository

Art conservation used to be simpler. There’s a reason etched in stone has become shorthand for something that’s remaining unchanged for eons. But even conservation of physical works has changed.

One of the reasons the Butler was built was because its founder and namesake, Joseph Butler, sought a fireproof home for his work, and the museum continues to give consideration to lighting and climate control. (When Zona became director of the Butler in 1981, the museum wasn’t even air-conditioned.)

Roemich is a chemist by training, with a Ph.D. in organic chemistry and field and teaching experience in archaeology. She fell into the field of art conservation, which is the nexus of several disciplines, including chemistry, engineering, and art history. Time-based media adds other fields, like computer science.

“When artwork has a plug, a very different set of skills is needed to keep it going and keep it public,” she says.

Even the concept of time-based media conservation itself can be an alien one to people trained to develop it, as Roemich discovered earlier this year when she hosted a multidisciplinary workshop between NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts and its Tandon School of Engineering.

“They’re training engineers and people who will create time-based media, but when I talked about conservation, they said, ‘And how do you spell that?’ They didn’t think of it.”

At its earliest stages, time-based media conservation involved the hoarding of items like cathode ray tubes, old computers, and incandescent light bulbs. “But you can only stockpile so many items before you have to start thinking about what to do with it,” Roemich says.

The most vexing time-based media conservation issue may be software-based art. If an artist uses commercial software to create a work, the copyright to the software needs to be acquired, and the software must be monitored for updates to properly display the art. If artists generate their own software, conservators need the software’s source code to recompile the work based on operating systems.

Additionally, any digital medium carries with it the possibility of corruption, which is concerning, says Ackerman.

“There’s no such thing as an archival digital print,” he says. “There’s a concerning push to replace materials with digital prints. They won’t last more than five to 10 years, and people aren’t investing enough in preservation. Digital prints are replacement, not preservation.”

Wharton says digital art, like all other art, needs a safe repository. “We need a server, we need it backed up off site, and we need a high manner of integrity,” he says.

When the file is uploaded on the server, says Wharton, he and his team create a checksum that will always represent that file-an algorithm that spits out a string of characters that identifies the bitstream of the file, which can then be compared later against the file to check for any type of corruption. “It’s standard in the computer industry,” he says, “but now museums are doing it, too.”

The checksum can be set up with an algorithm, and isn’t particularly labor-intensive, Wharton says. Once it’s set up, it can be done automatically any time a work of art is uploaded in a safe digital repository. But the process and the safeguards require the right type of person.

“All museums have some type of tech support,” he says. “But IT people aren’t trained to safeguard materials. You really need a combination of skills, including computer science and art preservation.”

An Era of Discovery

Beyond the technical issues in archiving and safeguarding time-based media, there are also ethical implications.

“We’re no longer just fixing stuff,” Ackerman says. “We’re dealing with abstract concepts around reproduction. We’re moving from physical treatment to stakeholder theory.”

Given the combination of camera, paper, ink and printer, you’re looking at potentially a million different combinations for one print, Ackerman says. And a piece of art can have a variety of stakeholders in addition to its creator, including people who are involved on a transactional level, like gallery representatives, auctioneers, insurance appraisers, buyers, and sellers.

“Collectors or museums may not know what they’re doing when they buy this kind of artwork,” Roemich says. “Do you buy the idea? Do you buy the material? Can you transfer it? What are its defining properties? If the artist is still living, how much do they want it to change? How much is set in stone, and how much can the owner define it?”

Optimally, Roemich says, those conversations are proactive, not reactive. But you never know when you have to deal with the work in the here and now.

“Sometimes you have to migrate it to a different (operating) system,” she says. “That’s a difficult decision, because you might lose the grounding of the artwork. If you know the technology is becoming obsolete, it’s a team decision: the conservator, the curator, engineers, scientists.”

One of the hallmarks of time-based media is the concept of variable art, a term that came into the art lexicon in the early 2000s and also poses its own ethical issues.

“Every time the artwork is installed, it’s going to be different,” Wharton says. “What’s the variance? What kind of interpretive authority is the artist giving to the owner? We now talk about various iterations of the installations.”

That flexibility can be an asset in conservation efforts, says Roemich.

“Time-based media doesn’t look the same everywhere,” she says. “It’s dependent on the exhibition and the interpretation more than traditional artwork. Owners, collectors, and museums should approach it in a playful way and try to account for the artist’s intent.”

As a result, res ipsa loquitur may remain a legal term, but in the art world, the thing no longer speaks for itself. Museums have gotten into the practice of interviewing artists about their work. And while artists are concerned with posterity for the sake of their work, they don’t necessarily want to consider an endpoint for it-or for themselves.

“This is forcing us to talk to artists and plan for these things,” Ackerman says. “It’s forcing us to identify what artists’ works are vulnerable. It goes into a weird territory where you think about death while thinking of the future.”

Sometimes, when an artist is no longer available, the museums conduct interviews with people who might have worked with the artist. Ackerman says many big-name artists have their own staff, which invariably includes someone devoted to time-based media. And the world of art conservation will have to keep up.

“When it comes to time-based media, we’re definitely still in an era of discovery,” he says. “But this is where things are going.”

('You Might Also Like',)