How Sun Basket, the 'Netflix of Food,' is trying to win the meal kit race

When the Mississippi River flooded in 1993, the thousand-person village of Valmeyer, Illinois, was swamped. In the aftermath, residents relocated to a higher elevation on top of a nearby bluff. Then-State Senator Dave Luechtefeld approached Joe Koppeis, a local businessman, requesting help developing the new plot of land, “New Valmeyer.” In doing so, Koppeis secured two consecutive 99-year leases to manage the 6 million square feet of limestone caves underneath the village.

Today, the village’s largest employer is one of Koppeis’s tenants. Sun Basket employs 1,700 workers across its corporate office and three distribution facilities. It is one of the most quickly growing companies in a fledgling industry: meal kits. It’s quite a spectacle — a Silicon Valley tech venture mailing boxes of food from the belly of a cave in rural Illinois. Natural refrigeration and insulation from the thick limestone walls make it a perfect home for Sun Basket’s new Midwest distribution hub. For the past year, the company has been using the cave to pack thousands of kits with ice packs and with portioned, perishable ingredients to subscribers across the region.

Carlos Bradley, Sun Basket’s director of talent and culture, drives with me over the Mississippi River into Illinois to tour the facility. White mist rising off snow in the cornfields obscures the view of the cave until we are directly in front of it. Suddenly, a wall of earth materializes, and three 50-foot rectangular openings chiseled directly into the rock-face offer a glimpse of the vast network of tunnels that makeup “Rock City.” It's not the only cave storage facility along the Mississippi river but it is among the largest.

Just before the pitch-black entrance stands a sign listing the cave’s tenants — Cargill, one of the biggest private food corporations on the planet and America’s largest private company, Little Caesars pizza, and the National Archives, which use the cave as a massive filing cabinet for HR documents and personnel records. Sun Basket’s logo, affixed to the bottom of the sign, is visibly the newest addition, but more tenants are in the pipeline. Koppeis is currently courting a major tech company to store its servers in the cave and cool them with water from the underground lake. The common thread among tenants is their dependence on refrigeration. Sun Basket is no different.

Driving along the tunnel road, now deep inside the cave, Bradley explains that the natural cooling and insulation cost half of what Sun Basket’s traditional distribution centers do. As a 5-year-old company in a new industry, Sun Basket is always in search of ways to streamline. To date, no meal kit company has proven that the business of packing and sending meal ingredients can be steadily profitable. Of the stunning 300+ companies currently trying, including high-profile names like Blue Apron and Hello Fresh, Sun Basket believes it has a chance at being the first.

This is the story of how and why Adam Zbar, Sun Basket’s CEO and co-founder, has built a company to compete in the cacophony that is meal delivery in the age of Amazon (AMZN). What is there to be gained, how likely is success, and who might profit from this $100 million endeavor? The global food supply chain has largely avoided disruption until this moment, in no small part due to the efforts of legacy conglomerates that benefit from the status quo. If Zbar and his team can reinvent one of the most basic elements of modern life, the way we cook dinner, countless restaurants, grocers, farmers, and consumers could see their day-to-day lives radically changed. But the failures of predecessors, stiff competition, and persistent problems at the core of the business model only make Zbar’s path to success all the more complicated.

‘I needed to ... change my life’

Adam Zbar (pronounced ZUH-bar) is a tall, slim, 49-year-old man with hair that is just starting to grey. He is the son of a doctor and a psychologist; his father a leading oncologist at the National Institutes of Health and his mother a practitioner of Freud’s psychoanalytic technique. Zbar began his management career after graduating from Pomona College when he took a job at McKinsey’s LA office, where he spent two years crunching Excel spreadsheets before leaving for a stint in filmmaking. He later returned to the business world to work a series of managerial roles at internet companies before launching his first start-up in 2006.

That startup was Zannel, an early microblogging site. TechCrunch called it “Twitter with pictures and video.” After four years at Zannel, Zbar and his partner Braxton Woodham created Tap11, an analytics platform that measured the impact of social media campaigns on Twitter (TWTR) and Facebook (FB). He sold both companies to Youtube’s founders for an undisclosed amount. After the sale, Zbar began raising seed funding for a same-day, artisanal wine and cheese delivery company called Lasso.

Zbar had been an active person for most of his adult life, but along with the hours required to steer budding tech companies came a deterioration of his eating habits. Throughout his time serving as CEO of these companies, Zbar gained 50 pounds and began to worry about his health. Zbar saw this moment as an opportunity to not just turn his personal health around, but to build a business out of it. “I needed to fundamentally change my life,” Zbar proclaims in Sun Basket promotional videos.

One of the first to join the team was Tyler MacNiven, a documentary filmmaker with shoulder-length red curls, who is more widely known for winning the ninth season of “The Amazing Race” in 2006. Tyler comes from what Zbar calls “the restaurant royalty family of the MacNivens.” His father, Jamis MacNiven, is the founder of Buck’s of Woodside, an iconic restaurant in Silicon Valley and a widely known haunt among powerful tech executives and venture capitalists. MacNiven, a cofounder, now serves as head of Sun Basket’s creative studio. By early 2014, Zbar and MacNiven needed recipes. They found professional chef Justine Kelly and pitched their idea to create what Zbar calls “the Netflix of Food” from the ground up.

Kelly had a sparkling resume: She worked her way up the restaurant industry ladder and served as corporate chef de cuisine at one of the Bay Area’s most acclaimed restaurants, The Slanted Door. Kelly was a competitor on “Iron Chef” with her then-boss Charles Phan, where they prepared snow fungus with almond and steamed almond banh beo cakes.

To secure her spot as Sun Basket’s head chef, Kelly auditioned for Zbar and MacNiven. “I don't have a resume, so I told them I would cook for them,” Kelly told me. “I think I made a ricotta stuffed herb chicken with panzanella, a salmon dish, and I made the steak with chimichurri which is one of our most popular recipes.” Kelly was offered the position immediately and Sun Basket was born.

Like many startups, Sun Basket’s origins were modest. MacNiven volunteered his own kitchen as a hub for recipe testing and packaging in the company’s earliest days. Boxes were sent locally to friends and family from MacNiven’s home, and once Zbar felt his idea was viable, Sun Basket moved into its first formal distribution center, a small, temperature-controlled warehouse in San Bruno, a city 12 miles south of San Francisco. When it outgrew the warehouse, Sun Basket expanded its West Coast operations and moved into the current distribution center in San Jose, now one of the company’s three hubs, alongside New Jersey serving the East Coast and the cave in Illinois serving the Midwest.

Sun Basket is now in its fifth year of operations, making it younger than its peers. Executives won’t disclose exactly how big the company is, but they say Sun Basket sends 1.5 million meals a month to people all over the country. In interviews, Zbar has referenced an annual revenue run rate of $300 million. On May 21, the company issued a press release stating that Sun Basket has grown at 80% CAGR (compound annual growth rate) over the past three years.

Meal kit demand is highly seasonal — customers tend to order more in the first quarter and pull back during holidays — so these numbers are fuzzy out of context. In his recently published autobiography, Zbar says the company’s value is nearing $1 billion, which if true, would place it in the unicorn class of startups.

Zbar’s time in tech gave him experience raising capital that has proven useful, as meal kit companies require significant cash upfront in their early stages. Zannel, the microblogging site, raised about $16 million. Its final round was led by three California-based firms, Alloy Ventures, U.S. Venture Partners, and Palomar Ventures, according to a 2008 press release. At Lasso, Zbar helped acquire $1.7 million of seed funding from firms including PivotNorth Capital, Baseline Ventures, and Relevance Capital.

Sun Basket has now completed its Series E funding round, bringing its total venture funding to $143.1 million, according to data compiled by CrunchBase. PivotNorth, Relevance, and Baseline have chosen to invest with Zbar again after Lasso, but there are also several new investors. Among them are August Capital and Sapphire Ventures, as well as Vulcan Capital, the investment firm owned by the late Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen and Unilever Ventures, the funding arm of the behemoth British-Dutch consumer goods company Unilever (UN).

Those watching Sun Basket, and its competitors, now want to know how long that cash will last. Fine-tuning the meal kit logistics puzzle is an expensive ordeal, and mistakes can be costly. If Sun Basket burns through the funds it has raised, the company will have to carefully consider its path forward. The lack of profit among those 300+ companies is a sobering fact making analysts and investors think twice about the industry business model.

A crowded field of meal kit competitors

When Sun Basket was getting started, the biggest names in the meal kit world, Blue Apron and HelloFresh, were already two to three years old, but neither were based in San Francisco where Zbar and Chef Kelly were working to assemble their team. Blue Apron (APRN) is headquartered in New York, and so far, is the only publicly traded meal kit company in the United States. As a public company, it is required to disclose more information than its private competitors like Sun Basket. These numbers shed light on the inner-workings of the business model.

According to filings, during the first quarter of 2019, Blue Apron had 550,000 subscribers, a 30% drop from its subscriber numbers the year prior. On average, during that quarter each of those customers generated $258 in revenue for the company. In the last quarter of 2018, Blue Apron posted a loss of $23.7 million, an improvement over its 2017 fourth quarter loss of nearly $40 million. In its most recent filing, the company was able to reduce its loss to about $5 million and posted profit on an adjusted EBITDA basis of $8.6 million.

Blue Apron’s transition from startup in 2012 to industry leader happened rapidly, and alongside that ramp-up came growing pains. An investigation published by BuzzFeed News in October of 2016 detailed a pattern of “health and safety violations, violent incidents, and unhappy workers” at the company’s Richmond, California distribution facility. According to the report, their facility grew from 50 employees in 2014 to over 1,000 at the time of BuzzFeed’s publication. As of January 31, 2019, Blue apron employed over 2,100 workers.

The increased hiring, according to BuzzFeed, resulted in a heavy reliance on staffing agencies for temporary workers. One employee was injured operating equipment she had not been trained for and others were working significant, paid overtime, sometimes stretching past midnight, according to the article. BuzzFeed reported that the growth also hindered Blue Apron’s ability to vet its hires internally, causing an unusually high amount of workplace conflicts ranging from physical fights to threats of shootings. Ultimately, regulators issued Blue Apron more than $20,000 worth of citations and penalties during its first two years of operation. Blue Apron disputes BuzzFeed’s reporting and is now compliant with rigorous safety standards. It highlights existing safety programs, and says the story was “a misleading representation of our company, our policies, our longstanding regulatory compliance, and the good work of our employees.”

Today, according to public records, OSHA officials have inspected Blue Apron facilities on seven separate occasions, more than half due to complaints, resulting in 25 violations classified as “general” or “other” (it has not accrued any “serious” final determinations, and all violations have been addressed). Sun Basket, for comparison, was inspected once in the wake of an accident and accrued five “other” violations.

The article had a lasting impact in the meal kit world. Incidentally, two months before the article came out, Sun Basket hired Carlos Bradley out in a newly created position as Sun Basket’s director of talent, culture, and engagement “with the mission of making it the best place to work for every team within the business.” Bradley is friendly and good with names; as he shows me around facilities throughout my time touring Sun Basket, he jokes with every employee we pass between the front desk and the backroom freezers. He was an early employee at Toms, the shoe company known for its buy-one-give-one philosophy. After Toms, Bradley has been involved with training and leadership development operations for the Cheesecake Factory and Apple (AAPL).

Bradley wears many hats for Sun Basket: he has handled graphic design projects, shot promotional videos, picked the decor and layout of multiple office spaces including the office inside the cave, but he sees crafting a corporate culture as the most crucial part of his job.

All distribution center employees go through an intensive, five-day on-boarding process that Bradley created. At one point along the tour, we walk into a meeting room to find new hires sitting around a conference table watching a PowerPoint presentation on workplace safety. One of the facility managers is leading the training session, and Bradley wants to get a sense of how it's going. “It’s common for people to cry at the end of the training,” because, Bradley says, they’ve never been given this kind of attention by an employer. “Some workers come from other meal kit companies where they say they received only 20 minutes before working on the floor.”

Sometimes, Sun Basket hires 10-20 new facility workers a week, and the majority of the company’s employees work in the distribution centers. Wages for warehouse jobs start around $10 to $16 an hour, according to GlassDoor. Bradley explains that “all employees in [the distribution center] are hired full-time with all the same benefits as corporate jobs.” They also all get a 50% discount on meal kits, and every Tuesday, Sun Basket sets up a farmers market of sorts for its employees. The market is filled with products that were damaged or over-ordered. Workers can fill up a bag of groceries for free, and the rest is donated to a local food bank.

The perks, however, do not make the nature of distribution center work any less taxing or monotonous. Sun Basket has implemented automation technology for its packaging processes at the distribution centers, but there are still last-minute menu changes and jobs that need human workers.

Tasks can range from filling and labeling hundreds of vials of single serving portions of maple syrup by hand to shifts wearing specialized suits in the protein freezer. When interviewing for these positions, potential candidates are required to do a test shift in the freezer, so they know what they’re signing up for. The work can be difficult, which makes hiring a challenge and employee retention, Bradley’s job, critical.

Blue Apron’s disastrous IPO

One year after BuzzFeed’s article, Zbar learned another valuable lesson: Keep an eye on Amazon (AMZN). On June 19th, 2017, Blue Apron launched a roadshow to begin gauging investor interest in an initial public offering. The Blue Apron team was promoting a $15 to $17 dollar price range for its shares, placing the company’s valuation near $3.2 billion.

This was a high price, partly because Blue Apron was seen as a market leader in a new industry that could disrupt a massive, multibillion-dollar grocery supply chain. Potential investors, however, had cause for skepticism about Blue Apron’s prospects because just three days before embarking on the roadshow, Amazon announced its plan to acquire organic grocer Whole Foods for $13.7 billion, in cash.

A marriage between an organic grocer with a brick-and-mortar store network spanning the U.S. and the nation’s dominant e-commerce company spelled out a huge blow for meal kits in the eyes of investors. Oddly, the financial press reported that despite fears over the acquisition, Blue Apron’s bankers were telling investors they were going to close their books early, “a sign of heightened demand,” according to CNBC.

In its prospectus, the company laid out its ambitious vision: “to build a better food system [by] transforming the way that food is produced, distributed, and consumed.” On the day of the IPO, Blue Apron filed with the SEC to amend its prospectus with a new price range of $10 to $11 per share, reducing the peak valuation to $1.89 billion, a 40% drop from the company’s earlier target. Anonymous sources quoted in a variety of articles covering the IPO ascribed the sudden price change to concerns surrounding the Whole Foods deal, as well as outsize marketing costs the company had to incur to recruit new customers.

Once markets opened, the stock was trading at the lower end of Blue Apron’s estimated range and closed at $10. By the end of the summer, the markets had shaved off half of Blue Apron’s value, and today shares are hovering at just a fraction of their opening price, less than $1.00. A Bloomberg headline in December declared “Blue Apron's 90% Drop Makes It Third Worst U.S. IPO This Decade,” with Blue Apron as the only non-energy company (which are susceptible to collapses in oil prices) in the bottom five. Its market capitalization today is around $135 million, a tiny fraction of the lofty $3.2 billion it had originally pitched to investors. In early April, Blue Apron’s CEO Brad Dickerson announced his resignation citing a desire to “pursue new opportunities,” according to a press release, and the company appointed Linda Findley Kozlowski, former COO of Etsy, as President, Chief Executive Officer, and a member of the Board of Directors.

Exactly how much Blue Apron’s disastrous IPO influenced Zbar’s thinking is unclear. A Reuters scoop from March of 2017 cited anonymous sources saying Sun Basket had retained banks to prepare for its own initial public offering. This was three months before the Blue Apron IPO, and Sun Basket was a smaller company at the time. It had not yet opened its Midwest distribution center in the cave. The Reuters article claimed that Sun Basket’s IPO was expected sometime in the second half of 2017, which would been just a few months after Blue Apron. The IPO never happened.

Germany’s Hello Fresh overtakes Blue Apron

Amazon has since launched its own fresh meal kit line run through Prime Fresh, the company’s grocery delivery service. Prime Fresh is a $15 monthly add-on to a standard prime subscription, which costs $119 per year or $13 per month. In total, access to Prime with the fresh add-on service comes out to about $300 a year, and this doesn’t include the cost of the meal kits themselves (usually between $8 and $10 per serving), or the $9.99 shipping fee for orders under $40. Strip away subscription fees and Amazon’s meals themselves are cheaper than Sun Basket meals, which will set customers back $11.99 per serving, or $71.94 for a box of three 2-serving meals.

Prime Fresh is still only available in select cities, and for now, the price tag makes it hard for Amazon to compete with the leading meal kit companies. But in the longer term, Amazon has the laid the groundwork for a successful meal kit operation. In addition to Whole Foods stores, Amazon is planning to launch a new, separate line of grocery stores as early as this year, according to the Wall Street Journal. Many meal kit companies are working toward partnerships with traditional grocery stores so consumers can purchase individual kits without a subscription or shipping costs, and Amazon already has a solid head start with its network of Whole Foods locations.

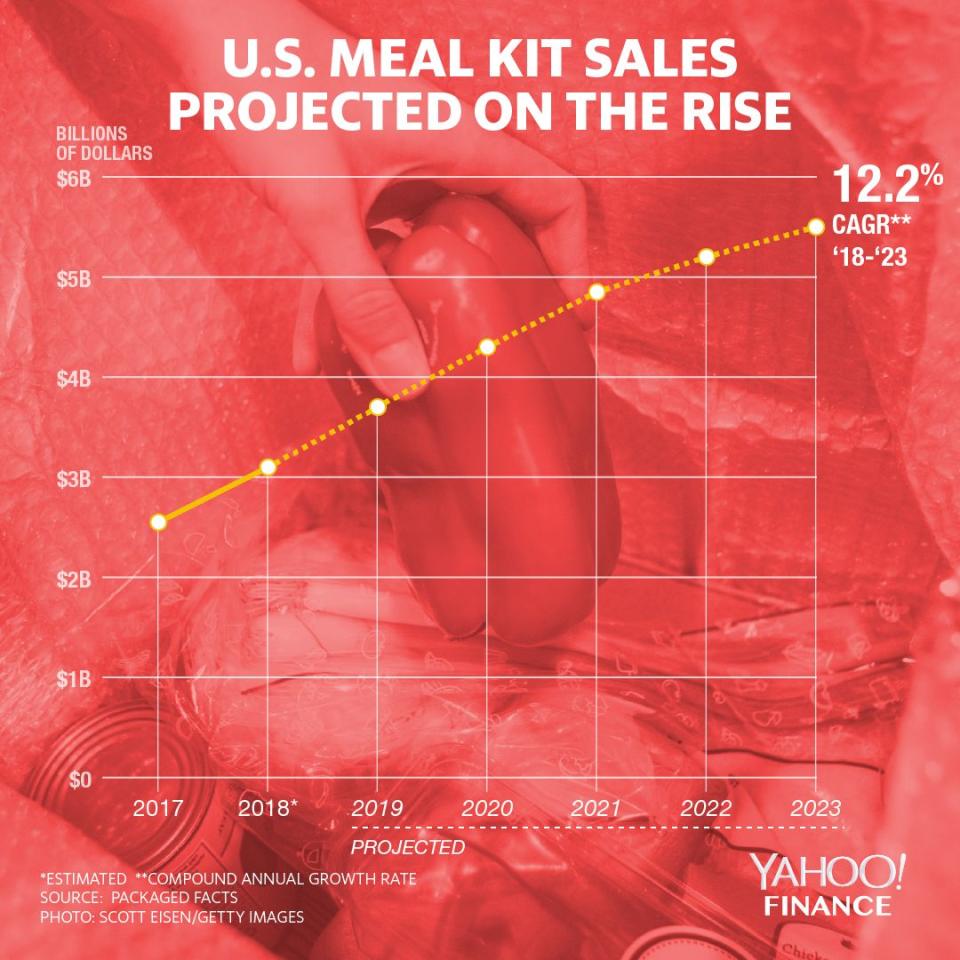

In addition to Blue Apron and Amazon, a third major player in the industry is the German company HelloFresh. Under CEO Dominik Richter, HelloFresh surpassed Blue Apron in early 2018, cementing its spot as the largest meal kit company in the world measured by market share. Together, the two companies account for half of all U.S. meal kit sales, according to a report prepared by grocery market research firm Packaged Facts.

The race to success is crowded, not just with big players but also the scores of niche meal kit providers that have popped up in the last few years. Companies like Purple Carrot, Terra’s Kitchen, Hungryroot, Global Belly, Thr1ve, and Plated all offer delivery services with a unique spin on recipes or marketing. There are companies like Daily Harvest and Frozen Garden that sell smoothie kits, and PeachDish that offers southern-style recipes. Gobble promises all meals require only one pot and are ready in 15 minutes, and Freshly and The Good Kitchen send meals that are already completely cooked, they just need to be microwaved.

The one commonality uniting the array of providers is their bottom line. If and when a meal kit company is able to show profits are feasible, it will be a major turning point for the industry. But before that can happen, industry leaders will need to solve a couple of entrenched problems.

The industry’s big challenge — churn

The trickiest and most persistent challenges facing Zbar are supply chain and customer churn. These issues are not unique to Sun Basket or even the meal kit industry more widely. Subscriber-based business models, like meal kits, are always battling the problem of churn, or the rate at which customers cancel their subscriptions. Thinking of the business like a funnel, Zbar is looking closely at the small portion of subscribers who “stick” to the sides and continue to pay for meal kits, as opposed to joining and quickly leaving. Those “sticky” customers are the most stable, and therefore the most profitable.

Each company has a different idea of what that “sticky” customer profile looks like, and this informs their advertising strategy. Companies that rely on subscription-based business models tend to spend heavily to recruit new customers, a cost known to industry professionals as customer acquisition cost, or CAC (rhymes with “whack”). Spending can take the form of a discount or a month-long free trial, and anybody who has listened to a podcast in the past few years knows how reliant meal kit companies have been on advertising.

In 2017, nearly one in every five revenue dollars that Blue Apron earned was spent on marketing costs. According to 2019 Q1 financials, the company has “deliberately reduced marketing spend” by 28%, revamped its strategy, and is now strategically investing in more efficient channels in an effort to push up the company’s bottom line.

In simple terms, if a meal kit company spends $100 to acquire a customer through advertising or promotions, and that customer pays $20 a week for her subscription, the company would need to retain her for at least five weeks before her subscription fees can begin to cover the costs of food, labor, and transportation that got the meal kit to her door in the first place.

Daniel McCarthy is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at Emory University’s Goizueta School of Business whose research specialty is “customer-based corporate valuation.” In other words, he uses customer data as inputs for statistical models to understand subscription-based businesses. Asked about the outlook, McCarthy says, “I'm not optimistic.”

After applying his model to Blue Apron’s Q3 financial results, McCarthy said “they have a large number of customers who will stay around for multiple years. The problem is that they are currently spending $150 to bring in customers that are worth on the order of $130-135. While they have said they will refocus their marketing spend to target those highly loyal customers, it could be harder than they think to distinguish them from everyone else. If you don't have any ability to be surgical about it, then you are kind of stuck acquiring all of them.”

Blue Apron has told investors that, for customers acquired in a given quarter, 80% of all the revenue that cohort generates comes from the top 30% of its most loyal customers in the following year. This startling statistic illustrates how critical targeted advertising can be.

Sun Basket’s customer retention numbers are not public, and the company did not make anyone from its retention team available for interview. In televised interviews, Zbar has repeatedly claimed that Sun Basket has “the leading retention rates in the space,” and offered that over 20% of customers stay longer than a year (the Blue Apron’s rate is around 15% according to research firm Second Measure). If true, there may be some merit to Sun Basket’s central idea that healthy recipe offerings and more personalization are what keep customers happy.

The second problem all meal kit companies grapple with is the supply chain. The Wall Street Journal has called meal kit distribution “one of the most complicated logistics riddles in the food business.” The major difficulties stem from the fact that almost every meal kit has a variety of fresh ingredients inside, which require different layers of temperatures in a single, insulated, cardboard box, and the recipes and ingredients are changing every week. It is Mike Wargocki’s job as the General Manager for Sun Basket’s West Coast operations to get it right.

Wargocki explains the challenge as we sit in an office overlooking hundreds of meal kits being stacked on pallets in preparation for shipment on the distribution floor. “This business is growing faster than anything I've been part of,” says Wargocki, who has had a 20-year career in the food industry. By volume, Sun Basket is now three times as large as it was when Wargocki joined in 2017, making his job three times as challenging, “but it's fun” he adds.

Working with fresh ingredients introduces food safety risks, and because the industry is still trying to establish itself, Wargocki takes extreme care to ensure that Sun Basket, as well as other meal kit companies, are equipped to deliver food safely. “One bad egg can ruin it for the whole industry,” he says.

The biggest risk for the company is meats, which need to stay frozen at the risk of endangering customers with food-borne illness. Ice packs are layered across the bottom of the box and meats are first in, so they keep the coldest. Fresh produce on the other hand, can’t be frozen but should be chilled.

In addition, even a perfectly packed kit with a controlled temperature ecosystem still has to arrive at the customer’s front door within a few days. This is where Sun Basket’s multiple distribution centers offer it an advantage. Shipping a box from an East Coast distribution center to a customer in, say, California or Oregon is not efficient, and the ingredients inside are unlikely to survive the trip. Spreading distribution centers across North America allows Sun Basket to reach a broader swath of consumers that are not as accessible to smaller companies, and to get them their food faster. Presently, Sun Basket meals ship everywhere in the continental United States except Montana and parts of New Mexico.

To do so, Sun Basket relies on a network of “last mile carriers” across the country that handle the actual door-to-door delivery. These temperature-controlled elements of food delivery are a significant cost bogging down meal kit profitability and are collectively part of the “cold chain,” a term used to describe the elements of a storage and distribution supply chain requiring refrigeration. Chris Nelson, Wargocki’s counterpart who oversees the Midwest distribution center, tells me whoever figures out how to perfect the cold chain will have a huge leg up.

Some analysts, however, are skeptical that a meal kit company will ever reach the finish line. Brittain Ladd is a supply chain expert with 20 years’ experience who most recently oversaw worldwide expansion of AmazonFresh before starting his own consulting company. “The entire business model is just stupid, it has never made sense,” he says. Ladd’s primary hang-ups are meal kit companies’ poor cost controls, over-reliance on advertising and customer retention, which are exacerbated during growth periods. “Every single person has a meal kit company no more than a mile from where they live called a grocery store. Within a mile, multiple grocery stores. It’s illogical,” Ladd says.

Ladd is not the first to suggest that meal kits are solving a problem of their own making. In response to the “why not use a grocery store?” question, Sean Timberlake, a former marketing manager for Sun Basket who oversaw PR for this story, says, “It's different than just getting groceries delivered to your apartment because these are recipes already defined, the ingredients are broken out. They're pre-measured. You don't really have to think that much. You open the bag, you read the recipe, it goes ‘one, two, three’ — you're done in 20 or 30 minutes and you feel like you've really accomplished something.”

Before reporting this piece, I would have agreed with Ladd, wondering how there could be so many companies founded on the same basic idea that people will pay a premium to have pre-selected recipes prepared and shipped to them when Amazon and other major grocery stores offer the choice of individual ingredients for less money in a quicker time-frame. But over the course of researching, I learned there is an element of meal kits that is more difficult to quantify, which is the intense, deep, personal relationship that people hold with what they eat and how they cook. Zbar is betting that this relationship, or “food tribes” as the company likes to call them, are what will allow Sun Basket to survive.

A descendent of the ‘farm to table’ movement

After driving along a few hundred feet of dark tunnel roads, Carlos Bradley, Sun Basket’s director of talent, culture, and engagement, parks his car in front of an unassuming glass door that seems to lead right into the limestone wall of the cave itself. Bradley walks through the door and greets the receptionist on his way into the St. Louis facility’s ordinary office space. Despite the total lack of natural light, it is easy to forget the facility is inside a cave, save for a few pieces of rock the company chose to leave tastefully exposed as decoration. There are a handful of cubicles, a conference room, and a small lounge area for employees. Framed photographs of professionally plated Sun Basket meals and quotes decorate the office walls. “The only way to do great work is to love what you do — Steve Jobs,” one reads with the white cursive font aesthetic of a motivational poster.

At the back of the office space, windows offer a glimpse into the heart of the distribution center. Bradley and Nelson, the cave’s operations manager, pass through a sanitation room where they wash their hands and don hair nets before starting the tour. Similar to the kits themselves, the distribution center is organized and divided by temperature. When ingredients arrive at the facility, they are placed into holding rooms branching out from the main prep space.

The warmest is the spice room, where dry ingredients are kept. Dozens of industrial size bags of spices ranging from paprika to Aleppo chili flakes stretch to the cave ceilings, their scents mixed beyond recognition. Small bags of chickpea flour, dried figs and rainbow quinoa are piled in crates around the room’s perimeter.

The next room is the fridge room, where fresh produce and herbs are kept until they’re ready to be cut, measured, and boxed. Crates of peppers, sage, eggplants, lemons, basil, carrots, zucchini, and cauliflower all have their designated homes here. On a pallet in the back of the room there are completed meal kit bags with labels that read “pan seared steak with Ajvar red pepper relish and watercress.”

The final storage room on the tour is the freezer. It is the coldest room in the facility, and its thick cave walls are coated with a white paint to seal out limestone dust. Sun Basket uses the room to store its proteins like fish and steaks, as well as the ice packs that line the meal kits. They are so remarkably effective at insulating the cold, Nelson tells me, that when an old tenant in the cave lost electricity, ice cream inside stayed frozen for days before the power was restored. At one point during the build, Sun Basket wanted to convert a subzero room into a warmer, 32-degree room. The team hauled in two industrial propane heaters and didn’t turn them off for two months until the room was above freezing.

Back in the main prep room, four women in white lab coats, hair nets and neon vests gather around a 10-foot conveyor belt feeding into a machine that seals baggies. They are dividing a mound of walnuts into individual serving sizes before the machine moves the piles of nuts down the belt and into a funnel, seals them into dime bags and drops them in a large crate. At another table, workers are pouring “stir-fry” sauce by hand into hundreds of gram jars, screwing on tops and attaching labels.

For efficiency, head chef Justine Kelly tells me the secret is literally in the sauce. She has developed hundreds of proprietary sauce recipes that are made in-house and can elevate a simple pork chop into a dish like “pork with orange chipotle glaze.” The sauces allow Kelly to take a complicated step out of the recipe directions. Kelly says, “Adam will look at a recipe and say, ‘that’s a great meal kit but it took you four pots, can we get it down to two?’”

The pre-portioned sauces, along with the ice packs, proteins, and fresh ingredients all coalesce at a much larger conveyor belt that runs the length of the facility. The conveyor belt is flanked by lines of human packers and dozens of crates of ingredients. When a bag appears in front of them, small LED lights flash to let the packer know which ingredients go inside. A worker puts an onion in the kit, presses the lit button, and the belt moves it farther down the line. Watching it all happen calls to mind the famous “I Love Lucy” scene, with a bit more order than the chocolate factory. At the last stop, all three of the customers’ meal kit bags are placed inside a box, a booklet of Sun Basket recipes goes on top before it is sealed, scanned, and ready to go out the door.

A few days later, the kit arrives at a customer’s door, like mine. Sun Basket provided me with a week’s worth of meals for the purpose of writing this story. On a Friday, I selected my three dinners from the week’s 18 recipe options: cauliflower risotto with shrimp, butternut squash and fried sage, steak au poivre with roasted winter vegetables and orange chipotle-glazed pork with coleslaw and roasted sweet potato.

By Tuesday my box had arrived, with every ingredient looking pristine like the photographs on Sun Basket’s website. Inside the steak meal bag was a note explaining that, because of a last-minute supply issue, the rutabagas had to be swapped for beets, a vegetable I’ve never been able to stomach. But after chopping them, coating them in olive oil and paprika, slow roasting them and serving next to a pan-seared peppercorn steak I was pleasantly surprised, as were my roommates whom I enlisted to help judge the meals.

This was the case for every meal I prepared. The cooking generally took 25-30 minutes and was simple but not so simple that I didn’t learn anything. The risotto dish taught me to fry my sage leaves before using them as garnishes, and the pork dish gave me a great coleslaw recipe I will be keeping. Overall, the experience was fun. I felt proud of myself as I plated a delicious, healthy meal well beyond my cooking ability, but wondered if there was more value in the educational aspects than the food delivery. After a few months’ worth of meal kits, would I feel confident enough to go to the farmers market, pick my own ingredients and do it all alone, and wouldn’t this be even more sustainable? As with most meal kit companies, the packaging was noticeably wasteful. Sun Basket has made strides in crafting recyclable ice packs and boxes, but as one reviewer notes, pulling three green onions out of their own Ziploc bag felt silly.

As for taste, reviews were glowing across the board. The food was genuinely delicious, there were never any leftovers, portions were sufficient, and one roommate is now considering signing up for Sun Basket herself. Finally, there is the question of healthiness. Sun Basket was, after all, born out of CEO Zbar’s desire to lose weight, and healthy, clean eating has been a core tenant of the company’s mission and marketing since day one.

Sun Basket sees itself as a direct descendant of the “farm-to-table” movement, a social-agricultural philosophy that advocates responsible sourcing of ingredients and encourages consumers to develop a deeper understanding of where their food comes from. Chef Alice Waters is credited with founding the movement in the U.S. through her Berkeley, California restaurant Chez Panisse. For Sun Basket, the philosophy translates to nearly all produce being certified organic, but the company has also struggled with misleading labeling. At the end of 2017, regulators found Sun Basket had “inaccurately communicated that Sun Basket meals contained all or almost all organic ingredients” when in fact some ingredients did not qualify.

The health focus also is evident in the work Sun Basket is doing to push its “food as medicine” concept. In December, the company appointed Dr. David Katz, a nationally recognized health and diet expert, as its new Chief Science Advisor. Dr. Katz will “help develop clinical trials designed to show that Sun Basket's approach to healthy eating can contribute to one's overall health, reduce the risk of preventable diseases, and dramatically reduce health costs,” according to a press release.

The hire comes at a time when Sun Basket is attempting a bold new tactic that is bound to send shockwaves through the industry: partnering with an insurer to defray the cost of its meal kits through subsidies. Forbes reports that Sun Basket is working “with a major insurer to conduct two pilot programs providing discounted boxes in California and a clinical trial measuring biomarkers in Louisiana diabetics.”

Sun Basket did confirm that its objective, ultimately, is to work with insurers and market their meal kits as a form of preventative medicine, backed by clinical trials that Dr. Katz will help run. But the team would not speak about which specific insurer Sun Basket is working with. “We talk to everybody,” said Timberlake. As of now, Sun Basket has taken a few first steps toward cementing its “food as medicine” strategy. Sun Basket has hired a team of dietitians working to produce articles and content for the Sun Basket blog about healthy dieting habits, weight loss targets, and explainers on the benefits of certain showcase Sun Basket ingredients.

Sun Basket is not the only meal kit service working to align itself with a larger health company. In December, just before its latest earnings call, Blue Apron announced a partnership with WW International (WW), the company formerly known as Weight Watchers, that allows WW users to select from a weekly rotation of meal kit recipes in line with the WW program. The partnership gives Blue Apron access to WW’s 2.8 million user-base in North America, more than four times Blue Apron’s current subscriber numbers, at a time when the majority of revenue decline is driven by customer loss as part of the company’s efforts to revamp its marketing strategy.

The renewed emphasis on health, not just pushing the superfood that’s in-vogue, but clinical-trial based, results-driven, certifiably healthier food, is an important bet for Sun Basket and its peers. Given the sustained quarterly losses and perilous cash position facing many of the meal kit companies, it could be one of the industry’s last chances to get it right. The online food and restaurant publication Eater speculated the industry is doomed, and consumer behavior trends do not paint an optimistic picture for the industry’s path forward.

Sun Basket faces intense competition not just from other meal kit companies, but also from brick-and-mortar grocery stores and restaurants. To get ahead, these companies have to try to decipher the complex and sometimes contradictory buying behaviors of their customers. Today, Americans are cooking more in their homes than they did a decade ago. A study by NPD Group found four in five meals Americans ate were prepared at home. Restaurant sales may be up, but this reflects increased prices, not increased traffic, which as of September had decreased consistently for the past 29 months, according to research firm MillerPulse and Bloomberg.

Millennials, unlike Americans on the whole, however, are spending less of their paychecks on groceries and more on food outside the home than previous generations, according to a USDA report. “Millennials allocate the highest proportion of their budget to food away from home,” the report said. It also found Millennials spend less time on food preparation and cleanup, 55 minutes less than Gen X’ers.

At face value, this is good news for meal kits, which market themselves to budget-crunched Millennials on the promise of minimal prep. But a Gallup poll from August found that a large majority of adults in the U.S. prefer shopping for groceries in physical stores, as opposed to online. “84% said they never order groceries online,” according to the study. In this case, “online” can mean purchasing meal kits or grocery delivery. When researchers focused their analysis, they found that 89% of those surveyed had never ordered a meal kit.

Not surprisingly, this young industry is already experiencing a period of consolidation. Since 2017, there have been at least five major acquisitions of meal kit companies, according to Packaged Facts. Grocery chain Albertsons acquired Plated in September of 2017 and has since pulled the kits from its shelves. HelloFresh is acquiring competitors: Green Chef in March of 2018 and Chef’s Plate in October. Kroger acquired Home Chef in June of 2018 and True Family Enterprises bought the now defunct Chef’d the following month. “Many commentators suggest that meal kit companies can only persist if they eventually become acquired,” the report said. Business operations carry significant costs which are not reflected in the price of the meal kits, and ultimately, Packaged Facts found “the current e-commerce subscription-centric business model is not working for many traditional players.”

3 possible paths for Sun Basket

Adam Zbar has, more or less, three paths forward as he considers Sun Basket’s future. The path of least resistance would be to remain private, but this path does not seem sustainable for long unless Sun Basket can do what no other meal kit company has been able to do: find a way to extract steady profits from the sale of meal kits. Unless Sun Basket can do this, raising new capital will become increasingly difficult as an unprofitable entity.

The second option for Zbar is to move forward with Sun Basket’s rumored IPO. Especially in the tech world, public offerings for as-of-yet unprofitable companies are becoming more commonplace. One study from the University of Florida found that 83% of the companies that went public in 2018 did so without proving they can make money, the highest proportion since 1980. An IPO would give Sun Basket a significant cash infusion and would elevate the company to an even footing with Blue Apron and HelloFresh, but it would also entail a loss of control to shareholders and a great deal of financial transparency.

Zbar still keeps his cards close to his chest in terms of performance data, and over the course of two months of reporting, never spoke with me for this story. Publicly, he reiterates the annual revenue run rate, $300 million, and revenue growth, 280% year over year. These two data points illustrate a quickly growing company but belie the heart of the business’s operating margins. If worrisome, those numbers would jeopardize Zbar’s ability to drum up investor interest during a roadshow, and potentially cause the asking price per share to plummet.

The third path is an acquisition. A large company’s backing would give Zbar the stability and resources to determine where exactly Sun Basket belongs in the ecosystem of the grocery industry. In return, the acquirer would gain Sun Basket’s advanced fresh food distribution network, and perhaps more importantly, Sun Basket’s talent that built the network from the ground up. The practice, known as an “acquihire” wherein a smaller business is purchased for the skills and expertise of its staff, is a favorite among tech giants like Google and Facebook.

But Sun Basket is unlikely to be acquired by a tech giant. One strong contender is Unilever (UN), the gargantuan British-Dutch consumer goods company. Unilever has a sales presence in 180 out of 195 countries. In May of 2017, their venture capital arm Unilever Ventures led a round of funding that brought in $9 million for Sun Basket.

Margins are contracting across the food and grocery industry; Morgan Stanley estimates they could shrink by as much as a third by 2023. In response, legacy conglomerates like Unilever are embracing an approach of aggressive acquisitions in search of fresh opportunity. The former CEO Paul Polman said at a conference in 2017, “We’ve had a very good strategy of steady and consistent acquisitions — the strategy is clearly working for us and we’re pretty happy with it.” Polman oversaw the acquisition of three companies in 2018, and seven in the year prior. Its catalog of newly owned companies includes Tazo Tea, Dollar Shave Club, organic food seller Mãe Terra, and beauty brand Sundial.

Polman was succeeded by Alan Jope on the first day of 2019, and with his new role came the task of steering this ocean-liner sized company toward growth. In early February, Jope placed his first bet and acquired Graze, a British healthy snack delivery service, for an undisclosed amount. Conspicuously missing from their list of subsidiaries is a full-fledged U.S. meal kit company, despite Unilever Ventures holding a stake in a number of food delivery services, including Sun Basket. Unilever may be waiting to see if the industry can manage profits, which would make upcoming quarters crucial for Zbar and his team to prove themselves.

‘Adam is actually working on a huge project’

Back in the cave, at the final stop on the conveyor belt where menu booklets are placed on top of the bags before the boxes are sealed, Bradley points out that their machines have the capability to put other items into the boxes at the last minute. Right now, Sun Basket doesn’t use this capability, but it would be easy to top off every box with, say, a free sample of some Unilever product.

When I sent my final request for an interview with Zbar in late January, Sun Basket’s PR team said, “Adam is actually working on a huge project and is fully booked until April.” That project could have been finalizing negotiations with the insurance company, introducing some new product line, a facility expansion, or any number of other endeavors. But if he was working on an acquisition, the next few months will be transformative.

Zbar talks with executives from other meal kit companies, and sources say he had lunch with a major meal kit CEO a few days before my tour. The thinking is, if one high-profile meal kit company fails, it hurts investor perception of the entire industry, so Zbar collaborates with other leaders as a sort of symbiosis. It’s not clear if this information sharing will be enough to carry the industry to a state of stability, but until the answer is certain, Sun Basket will keep shipping its boxes.

Two months after I visited San Francisco, Zbar released his autobiography. In it, he writes about the various successes and failures, personal and professional, that have shaped him. He ends the book with an anecdote from his time studying abroad as a college student in Germany. Zbar decided to go skiing in the Austrian Alps but got lost traversing the backwoods because he couldn’t read the German trail signs. A stream halted his run, so Zbar carried his skis through the frigid water for hours looking for signs of a town.

Zbar was elated when he saw a tram line and began skiing downhill alongside the track. Suddenly, Zbar was free falling. He had skied off the side of a cliff, and moments before a rocky impact, a tree branch caught the back of his ski suit and saved his life. He finally made his way to a town, where a bartender explained where he was. “Somehow by the force of my will, my stupidity, and the kindness of the universe, I’d skied from Austria to Germany,” Zbar writes.

The earliest meal kit companies were not created until the recovery from the last financial crisis was well underway and are now benefiting from record low interest rates and one of the longest periods of economic expansion in U.S. history. Zbar has built an impressive company with scores of loyal followers but has yet to see that loyalty tested in more trying times of a financial downturn. Meal kit companies across the country have thousands and thousands of employees on their payrolls, and investors have collectively sunk well over a billion dollars into them. It is not clear how resilient they will be when the next recession comes. What is clear is that as Zbar glides down the mountain and countless others follow his tracks, those who reach the bottom safely will be the ones who stop to read the signs.

Nic Querolo is a freelance writer and a recent graduate of the Columbia Graduate School of Journalism.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn,YouTube, and reddit.

Clarification: This article originally stated that Sun Basket had revenue growth of 280% year over year, citing interviews with Zbar. The article has been updated to reflect a May 21, 2019 press release stating that Sun Basket has grown at 80% CAGR over the past three years.