The All-Time Greatest Cheats in Motorsports History

Racing sponsors might like the bright, easily identifiable colors that help sell their products. Drivers surely go for the black and white of the checkered flag, and fans prefer green flags to other color options. But to crew chiefs and technical directors there is no more beautiful color than gray. That’s because gray is somewhere between the light and the dark, between the legal and the outlawed. The gray area between the lines of a rules book is where teams find an advantage over their less-clever adversaries.

Innovation is neither inherently moral nor immoral. It simply is. Cheating is immoral, of course. But even when someone is clearly breaking the rules, there are still shades of gray. Was the cheat so ingenious, like the Toyota example below, that even those tasked with policing such things couldn’t help but acknowledge its brilliance?

This story might be the six cleverest cheats in motorsports, but that’s not exactly true. The cleverest ones are those that provided an advantage and went undiscovered— the ones that only a few people know about because they are the ones who thought it up. Here are great ones that we know about.

Restrictor Plate-gate

World Rally Championship, 1995.

For three consecutive years (1992-’94) the World Rally Championship (WRC) title went to Toyota Celica Turbo drivers Carlos Sainz, Juhan Kankkunen, and Didier Auriol. The streak ended with a resounding thud in 1995—a year in which the WRC mandated restrictor plates to limit air intake and slow the cars in the name of safety.

Toyota Team Europe engineers thought they found a way around the restrictor-plate regulation by finding a way around the restrictor plate. It was a cheat so subtle and ingenious that it wasn’t identified until the penultimate race of the ’95 season. That’s when a tech inspector discovered a hairline fracture in the Celica’s restrictor plate. While the plate itself was legal, inspectors discovered that it was installed and tightened into place using a set of hidden springs (Belleville washers) that would push the restrictor plate 5 mm farther from the turbo than the rules mandated and allowed some air to enter the turbo without passing through the plate. It was good for an additional 50 hp. But the real genius of the contraption was that if inspectors tried to have a peek inside, the mere act of loosening the hose clamps that held it together would release tension on the springs and return the restrictor plate to a legal position. FIA President Max Mosley called the cheat “the most sophisticated I’ve ever seen in 30 years of motorsports.” Still, the Toyota team was banned from the WRC for one year.

And the Smokey goes to ... Smokey!

NASCAR, 1967-68.

If there were an Oscars for motorsports cheating, the statuette would be cast wearing a cut-down cowboy hat and smoking a pipe. The flat-hat-wearing, pipe-smoking Smokey Yunick is nothing short of a folk hero to motorsports tinkerers and fans of general impishness. Stories of Yunick’s rule-bending are legion. And some of them are even true. But even by his stratospheric standards, Yunick’s NASCAR Chevrolet Chevelles of the late 1960s were something special. So shrouded in folklore are these black-and-gold Chevys that people believed they were 7/8th scale models. They weren’t. Instead, they were full-size vehicles with a multitude of subtle and clever modifications, some of which were not exactly by the book.

The chassis used in 1967 had been custom-built by Chevrolet, which was then providing back-door support to certain racers, including Yunick. It had a reworked suspension and a roll cage that, tied to the stiff frame, made it effectively a tube-frame racer. Chevy also undertook an exhaustive aerodynamic study of the Chevelle’s body on behalf of Yunick’s car. It easily took pole position for the 1967 Daytona 500 against well-funded factory teams from Ford and Chrysler. But engine problems cut its race short, and it was heavily damaged in a severe crash shortly thereafter. But in 1968, Smokey came back with another Chevelle much like the 1967 car, although he built this one himself. The chassis was similar to the earlier car, with the body set back a couple of inches on the frame for better weight distribution. And the aero trickery was impressive. The chrome front bumper was deepened to act as an air dam. Rain gutters and glass trim were made flush with the body. The roof’s trailing edge was upswept like a spoiler. The underbody was smoother than stock with a modified floorpan for clean airflow. This time NASCAR called foul and banned the Chevelle from the ’68 Daytona 500 unless Yunick changed nine offending aspects of the car. The story goes that NASCAR officials even removed the fuel tank for inspection only to see Yunick start the car sans gas tank and drive it back to the pits, saying, “better make it 10.” Yunick noticed that the rule book specified a maximum volume for the fuel tank, but it didn’t say anything at all about fuel lines.

So, depending on which re-telling you believe (even Smokey had multiple versions), he replaced the normal fuel line with 11-foot-long, one- or two-inch-wide fuel line that added either two or five gallons to the car’s total fuel capacity. It’s such great story, it barely matters which version is true. As Yunick wrote in his autobiography: “Was this car a ‘cheater’ Smokey? You’re goddam right it was.”

Winging It

Formula 1, 2011-14.

Red Bull Racing’s four consecutive F1 championships from 2010 to 2013 were as much a product of innovation, technology, and living in the gray area of the rulebook as they were the driving skill of four-time F1 champion Sebastian Vettel. In 2011, Vettel drove Red Bull’s RB7 to his second consecutive championship with 11 wins and 15 poles in 19 races. The RB7 featured a flexible (and in the eyes of many of its rivals, illegal) front wing.

The wing allowed the car to pass tech inspection at a legal ride height while standing still. However, not unlike Brabham’s BT49C from 1981, the car was a different beast at speed, as the wing was designed to deflect down as the car reached race speed (movable aerodynamics were outlawed in F1 in 1969), lowering the gap between wing and track for an aerodynamic advantage over the competition. The wing was designed by careful layering of carbon composite materials, allowing it to flex outward and down when subjected to the loads created by a car at speed. The wing passed inspection all season and into 2012, but by 2013 the FIA had incorporated stricter testing and was able to crack down on Red Bull’s flexible bodywork. End of story, right? Wrong. At the final race of the 2014 season, Red Bull was penalized for flexible front wings in qualifying, and forced to start the race from the back.

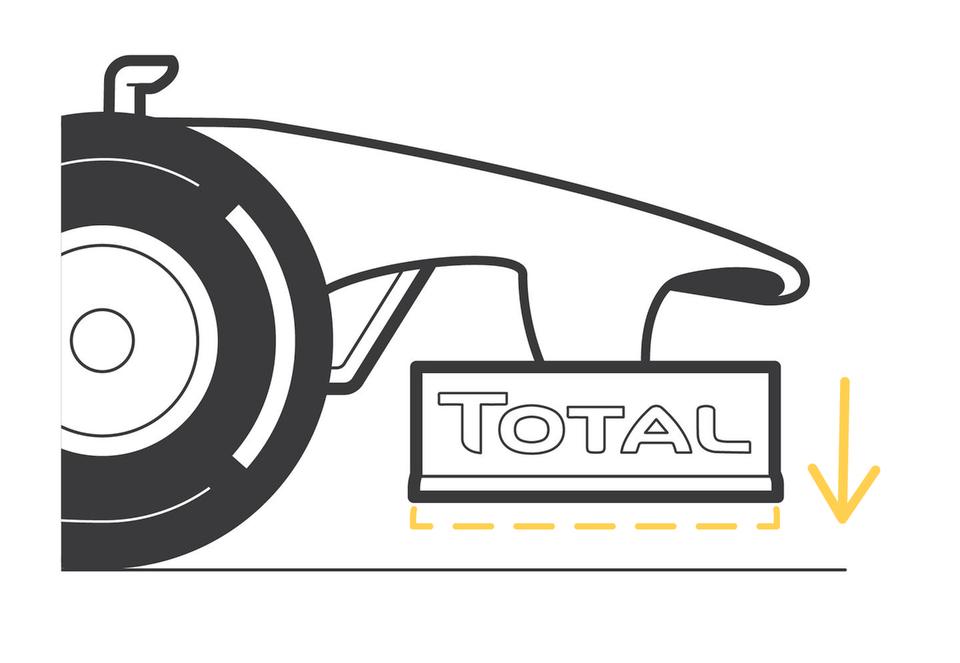

Low Rider

Formula 1, 1981.

While there is a fine line between cheating and innovating, Formula 1 racing engineer and car designer Gordon Murray knew he was pulling a fast one in 1981 when he unleashed a Brabham BT49C on the field. The car used a hydro-pneumatic suspension system that allowed it to run lower to the track than the rules allowed, thereby improving its aerodynamic performance. At a standstill, the car had the requisite 6 cm of ground clearance because its hydro-pneumatic suspension cylinders were full (half with air and half hydraulic fluid). But once the car was up to speed, the aerodynamic downforce provided by the front and rear wings would push down the body, expelling just enough of the cylinder’s contents to a central reservoir, thereby lowering the ride height. The car would remain in its lowered state until the end of the race, when a slow cool-down lap would relieve pressure and return the car to a legal ride height. Well, reasoned Murray, it was legal when official measurements were taken at a standstill; the car must therefore be legal. To divert attention from his trick suspension, Murray mounted a useless aluminum box with some wires sticking out of it. The system was discovered and its legality debated by rivals following Nelson Piquet’s win with the Brabham in Argentina in the third race of the ‘81 season. By the next race, the controversy subsided as similar systems were being used by many competitors. Whatever advantage Piquet gained early in the season was just enough, however, as he won the 1981 F1 title by a single point.

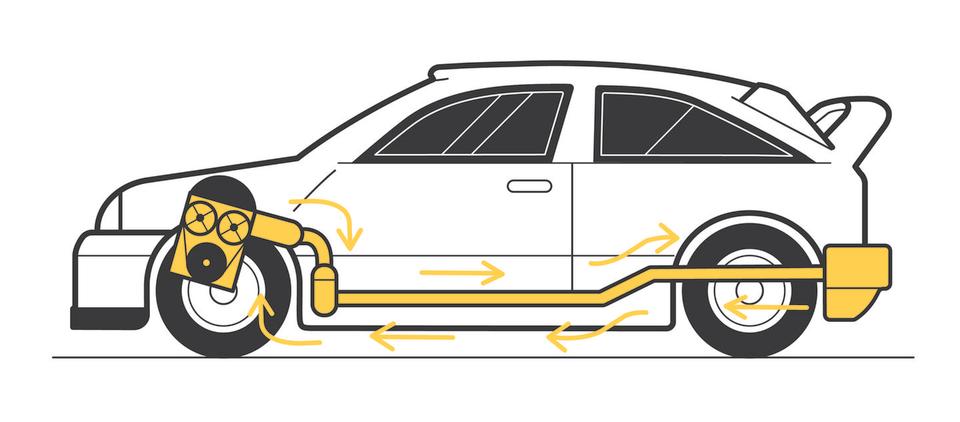

Brake Dancing

Formula 1, 1997-98.

The McLaren F1 team lived in the rule-book gray area during the second half of the 1997 and into the 1998 season, thanks to a second brake pedal that allowed drivers David Coulthard and Mika Hakkinen to activate just one of the rear brakes when desired. The brainchild of American engineer Steve Nichols, the system helped reduce understeer by pivoting the McLaren MP4/12 into corners. It took the eye of an F1 photographer to capture a glowing rear brake while the car was racing out of a turn, which caught the attention of the competition. McLaren engineers later claimed that the innovation, which was put into play for the second half of the 1997 season, was worth as much as a half second per lap. Did it work? In 1997, Coulthard won two races and finished third in the championship, while Hakkinen won his first career race and finished sixth. Rival Ferrari led the protest, claiming that McLaren was doing something that fit the description of illegal four-wheel steering. The FIA agreed and banned McLaren’s “brake steer” early in the 1998 season. That would be the same 1998 season, by the way, in which Hakkinen won eight of 16 races and the F1 championship.

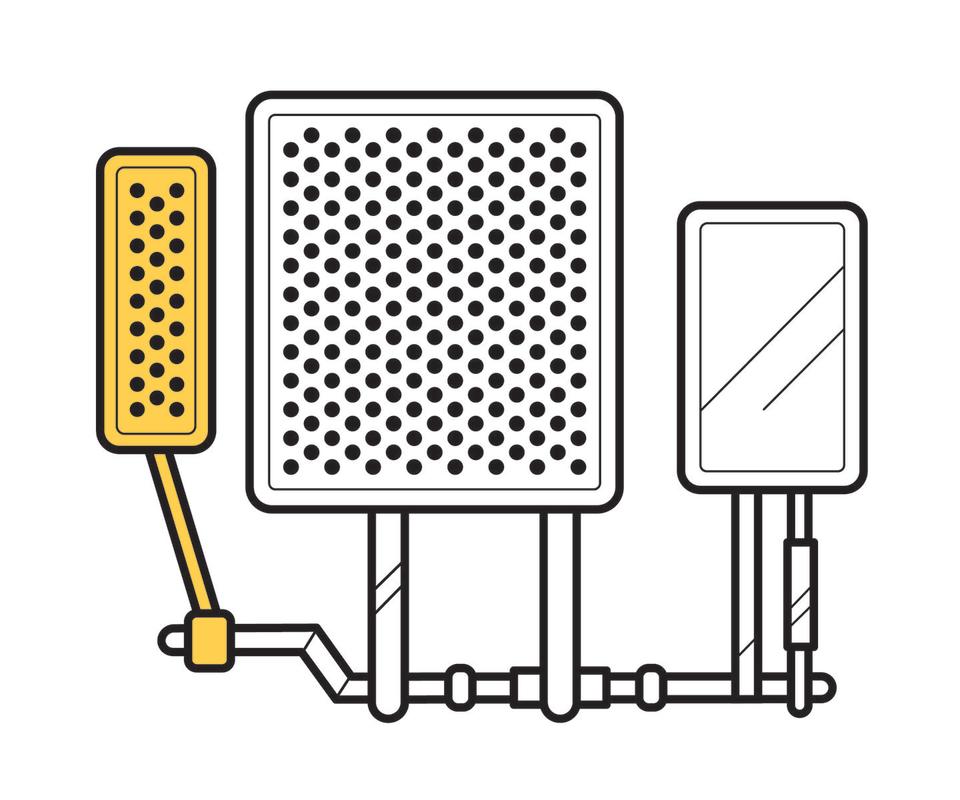

Air Supply

World Rally Championship, 2003.

Air plus fuel equals power. This is why sanctioning bodies from all forms of motorsports look to limit power by restricting the amount of air allowed into an engine. We’ve already seen how Toyota got around air restrictors in ‘95. Ford had a different idea. In 2003, the Ford Focus RS rally car used recycled air to boost performance. Ford engineers built an air tank and hid it under the rear bumper cover. The tank, constructed of 2 mm thick titanium, harvested and housed pressurized air from the turbocharger during off-throttle driving. On long straights, the drivers could release the stored air, which was fed back to the engine’s intake manifold through a titanium pipe. And, coming from the rear, the forbidden air bypassed the mandated restrictor plate. This little trick increased power by five percent. Ford’s top driver in the WRC that year, Markko Martin, won two rallies and finished fifth in the championship. He was also disqualified once, as the cheat lasted three rallies before it was discovered and banned.

You Might Also Like