Translating the Bible—Into an E-Book That Works on Any Phone

Most tech companies care about early adopters. The people who make Bible apps care about every last soul, which means they sometimes end up in distant realms of the linguistic and technical worlds.

In a recent essay on "Christianity and the Future of the Book," I wrote just a bit about the possible consequences for global Christianity of the rise of the cellphone -- and especially the cellphone as an instrument for reading the Bible. They think about this a lot at an organization called YouVersion. YouVersion produces and disseminates Bibles in many languages with a focus on creating readable mobile-ready texts. (How many languages, you ask? Well, take a look.) If you check out their mobile app page you'll see that they leave few platforms unsupported, including ones that have relatively little traction in the U.S. but millions of users in the developing world.

YouVersion is part of an endeavor called Every Tribe Every Nation -- the name derives from phrases in the book of Revelation (5:9 and 7:9) -- whose goal is "to provide God's Word in everyone's heart language in a format that they can engage with so that their lives may be transformed." (The phrase "heart language" is used primarily, as far as I can tell, by Christian Bible translators.)

So if you have a moderately smart phone, or even a pretty dumb phone with a rudimentary web browser, YouVersion is ready to provide a Bible to suit you, whether your heart language is Norsk, Potawatomie, Bahasa Indonesia, or Hawai'i Pidgin.

In Hawai'i Pidgin, incidentally, the book of Acts is called "Jesus Guys" and it starts like this:

Aloha, Teofilus! I wen write one nodda book fo you befo, an I tell you all da stuff dat Jesus wen do an teach from da start, till da time God take him up inside da sky. Befo he go up, he tell da guys dat he wen pick fo send all ova, wat dey gotta do. Godʼs Spesho Spirit wen tell him all dat. Now, afta Jesus wen suffa, he let da guys dat he wen pick see him, an he prove dat he stay alive fo real. He stay show up by dem fo forty days, an wen tell dem how everyting stay wen God stay King.

Here's a standard NIV translation of the same passage.

In my former book, Theophilus, I wrote about all that Jesus began to do and to teach until the day he was taken up to heaven, after giving instructions through the Holy Spirit to the apostles he had chosen. After his suffering, he presented himself to them and gave many convincing proofs that he was alive. He appeared to them over a period of forty days and spoke about the kingdom of God.

Mark Howe, who works for YouVersion, has commented, "At first sight - ok, at second sight too - the text is quite entertaining. But this is not a novelty Bible. Eight million people speak Hawai'i Pidgin as their 'heart language.' Even without being a fluent Pidgin speaker, it's clear that the translators have worked hard to bring the text to life within that language."

In his terrific essay on his journey to a Christian rock festival, John Jeremiah Sullivan notes that "Christian rock is a musical genre, the only one I can think of, that has excellence-proofed itself." This is equally true of much of the evangelical Christian subculture, which tends to be unimaginatively derivative of the purportedly "safer" aspects of the culture at large. But in the world of Bible translation things can be different. Over the past several decades missionary groups like the Wycliffe Bible Translators have sometimes been among the first visitors to remote cultures to learn those cultures' languages -- and to do some pretty thorough (though often amateurish) ethnographic study: after all, you can't translate the Bible into a language until you understand not just the linguistic vocabulary of a people but their cultural vocabulary too. (The whole discipline of anthropology has deep roots in Christian missions.) That this study is done for explicitly conversionist purposes makes the Wycliffe translators, and other Christians who do similar work, immensely controversial; but the bodies of ethnographic and linguistic knowledge they have amassed are remarkable.

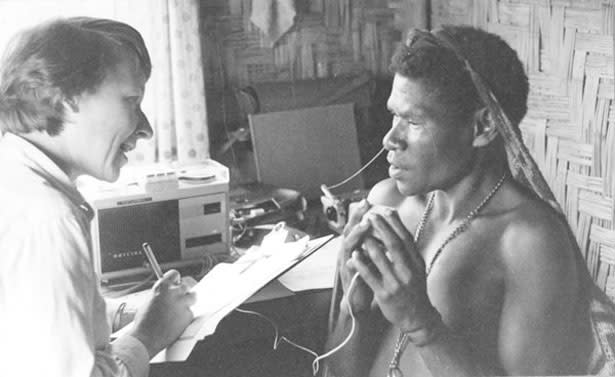

(One example: my long-ago colleague Vida Chenoweth, who had to abandon her career as a professional classical marimbist -- apparently she was the first one -- after a severe injury to her hand. She then traveled to New Guinea as a Wycliffe translator, discovered a deep interest in the musical traditions of the cultures she visited, became a major figure in ethnomusicology, and eventually passed along hundreds of her field recordings to the Library of Congress.)

Vida Chenoweth at work. Credit: Library of Congress

Now, it turns out, the old missionary impulse is being turned towards some extremely difficult technical challenges: as Mark Howe has said, "For all the issues that are still to be solved, ETEN is trying to do things that the world's biggest tech companies haven't cracked yet, such as rendering minority languages correctly on mobile devices. There's a unity among Bible translators and publishers that stands in stark contrast to the fractured, fratricidal smartphone industry." And of course, once these technical challenges are met, it won't be Bibles only that people can get on their mobile devices: whole textual worlds will open up for them. Reliance on cellphones in the global South isn't always a good thing, but when those phones provide free access to information, they're a great boon.

So whatever your views about the Christian missionary enterprise, it's safe to say that insofar as people like Howe succeed in solving these problems, some of the world's smaller "heart languages" will stand a better chance of surviving, and maybe even thriving, in an increasingly digitized world. And that's pretty cool.

More From The Atlantic