Trump’s outdated view of the economy

Donald Trump is ’70s Man. He loves beauty pageants. He puts ketchup on his steak. And he thinks the surest signs of economic might are thriving smokestack industries churning out the raw materials for skyscrapers and locomotives.

Businesses and investors everywhere are on edge as Trump, himself a lifelong builder, is now attempting to translate his industrial-era economic worldview into action. Trump has promised to impose tariffs of 10% on all aluminum imports to the United States, and 25% on all steel imports. The stock market has wobbled on that news, and now Trump’s top economic adviser, former Goldman Sachs president Gary Cohn, has quit in frustration over Trump’s tariffs. Investors have viewed Cohn as the strongest bulwark against economic nationalism that could trigger damaging trade wars, and his departure will undoubtedly unnerve markets further.

“If you don’t have steel, you don’t have a country!” Trump tweeted, in all caps, on March 2. It’s also true that you don’t have a country, or at least a prosperous country, if you don’t have software, data centers, accounting firms and teachers. Yet Trump talks little, if at all, about the segments of the economy that are the biggest source of wealth and power these days. And he seems ready to risk damaging the economy to protect industries that represent a small and declining share of American production.

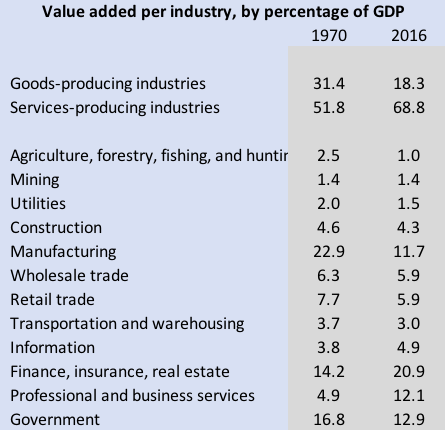

The U.S. economy is in a long transition from building stuff to generating services, a trend that has been underway since the end of World War II. Goods-producing industries accounted for 41% of total output in 1948. Today, it’s just 18%. Services, meanwhile, have risen from 47% of gross domestic product in 1948 to 69% today. Here’s a breakdown of the changes by industry:

This isn’t the result of any policy out of Washington. It’s just the way modern economies evolve. As the economy becomes more productive, generating more wealth, capital naturally flows to activities that earn the highest return. Those tend to be innovative new industries that aren’t easily copied, where the value added by workers is high. So-called commodity products that are easy to duplicate—such as basic steel products, along with textiles, plastics, toys and many other routine things—offer a declining return on investment, and sometimes hardly any return. That’s why they tend to migrate to developing countries where production and labor costs are lower.

Trump is right that the United States needs a healthy steel industry. But it already has a $90 billion steel industry, and a $41 billion aluminum industry. The Pentagon says it can get all the steel it needs domestically, and that accounts for just 3% of the total domestic supply. That leaves quite a lot left for all the private-sector products that require steel.

The United States also imports a lot of steel, and it’s true that cheap foreign competition has caused American job losses. But at the same time, booming industries such as renewable energy, hydraulic fracking, warehousing, data analysis and mostly anything relating to digital technology or health care have created millions of new jobs. Some companies in these industries can barely find workers. Pay is going up in many parts of the country, and workers willing to get new skills, certifications and education often enjoy big income gains—as has almost always been the case in the U.S. economy.

There’s nothing wrong with championing the industries of yore. But there is something wrong with actions to protect those industries at the expense of others, which is what Trump’s tariffs would do. Analysis by the nonprofit group Trade Partnership says Trump’s protective tariffs would boost steel and aluminum employment by about 33,000 jobs. But they’d kill 179,000 jobs elsewhere in the economy, because of the higher prices manufacturers of cars, appliances, industrial equipment and many other things would face. That’s a net loss of 146,000 jobs—before accounting for retaliatory measures enacted by other countries that would hurt U.S. exports to other countries and further dent production.

The kind of global trade Trump seems to have a problem with does generate abuses. China’s communist government subsidizes that country’s enormous steel industry, which has caused a big overcapacity problem worldwide. But the U.S. government has also imposed numerous penalties on Chinese steel importers as a result, and now has more tariffs in place on steel imports from China than from any other country. Chinese steel imports, not surprisingly, plunged 82% from 2006 to 2016. China isn’t even among the top 10 steel importers to the United States any more.

That’s not good enough for Trump, apparently. His steel and aluminum tariffs would apply to all countries, and they wouldn’t be based on any finding of unfair trade practices. Instead, they’d be based on an obscure law that allows the president to impose tariffs as needed to protect national security—like, during a war. There is no war, of course. Trade expert Gary Hufbauer of the Peterson institute for International Economics recently told Yahoo Finance that Trump’s national-security pretext is a “complete sham.”

If Trump goes through with his steel and aluminum tariffs, the next step could be dismantling portions of the North American Free Trade Agreement, or withdrawing from it completely. Most economists say there are elements of NAFTA that can be updated and improved. But they also say the 25-year-old trade deal has generally made each of the three trading partners, Canada, Mexico and the United States, better off. Still, Trump wants products purchased in America to be made in America, case closed. He doesn’t seem to care about supply-chain efficiencies, low prices for consumers or the second-, third- and fourth-order effects of telling companies how and where to direct their capital.

If Trump really wanted to turbocharge the U.S. economy, he’d focus on the industries of the future and shepherd as many American workers as possible into those. That means improving education and making sure kids get schooling that prepares them for the digital economy. The government could make it easier for people to move where the jobs are and get needed technical skills mid-career, or even late-career. If Trump wants to take extraordinary measures to protect vital industries, he should be making sure the United States dominates vehicle electrification, quantum computing and the many revolutions artificial intelligence is likely to spawn. China is investing in all those fields, and not shooting itself in the foot along the way.

Confidential tip line: rickjnewman@yahoo.com. Encrypted communication available.

Read more:

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success. Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman

Follow Yahoo Finance on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn