Health insurance premiums are headed way higher

Some family budgets are stressed to the limit by the cost of health insurance and out-of-pocket medical expenses. This burden, unfortunately, is likely grow much heavier.

New analysis by the Penn Wharton Budget Model forecasts that the real cost of health insurance premiums will increase by 90% over the next 40 years, after adjusting for inflation and economic growth over that time. In plain English, that means paying for health insurance would take nearly twice the bite out of the family budget that it takes now.

The higher cost of premiums, relative to income, means fewer people will buy and more will go uninsured. The Penn Wharton model forecasts an increase in the uninsured rate from 10% now to 27% in 2060. “We’re going to have people dropping out of the insurance market, even when they get group insurance provided by an employer,” says economist Kent Smetters, director of the Penn Wharton Budget Model. “These are fairly significant increases we’re projecting.”

The Affordable Care Act, passed in 2010, helped lower the uninsured rate from nearly 18% to about 10% today. That’s 19 million additional Americans who have coverage since Congress passed the law. Many analysts think—or at least hope—the uninsured rate will stay at this new, lower level, and perhaps improve more.

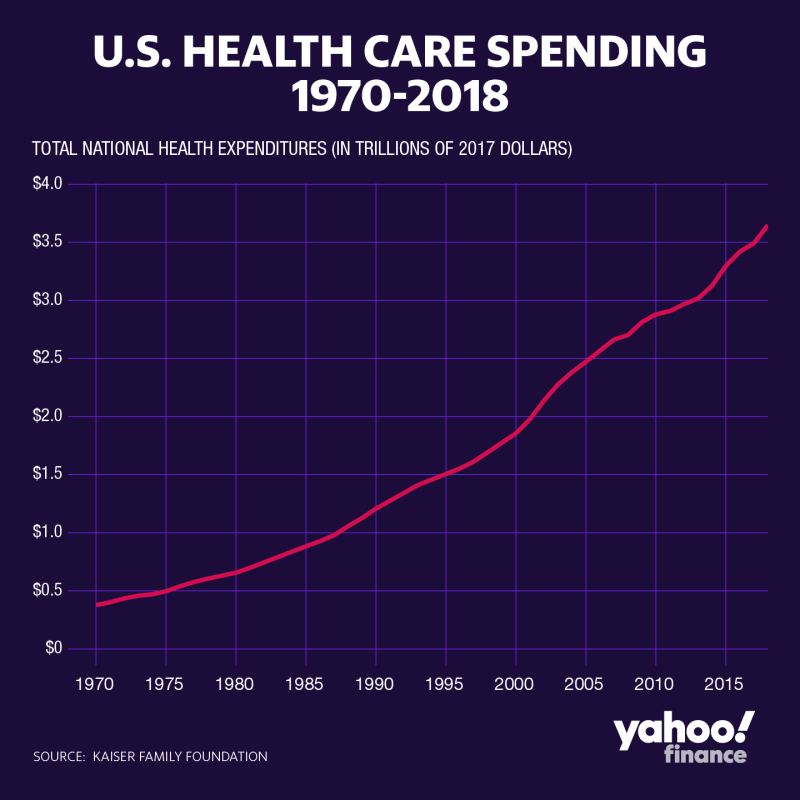

But the Penn Wharton analysis predicts the opposite will happen, for two reasons. First, health care costs are growing faster than both the overall economy and wages, and the cost of insurance—premiums—must rise by a similar amount. So health care costs will take a bigger and bigger bite out of the typical paycheck for as far as the eye can see.

As insurance gets increasingly expensive, more people are likely to go without it, even if their employer offers it. And the people most likely to opt out of insurance are the healthiest (and usually youngest) people who are cheapest to insure. This creates an “adverse selection” cycle, with the pool of covered people becoming sicker, on average, and more expensive to insure. That pushes up premiums even more. “Excess cost growth is magnified by dropouts along the way,” Smetters tells Yahoo Finance. “It’s those two effects working together.”

Larger chunk of income spent on health insurance

Americans spend 11.5% of their income on health care, on average, a share that has been rising steadily for years. A decade ago, health care spending took up just 7.8% of the typical budget. Employers that offer health insurance cover 77% of the cost of premiums, with worker contributions paying the rest. But most economists think the ever-rising cost of health insurance pushes wages down, since businesses must spend the money on health coverage instead. Rising health care costs hit workers both directly and indirectly.

The 40-year window of the Penn Wharton analysis is obviously a long period of time, and many things could happen to improve (or worsen) the outlook for health care spending. Democratic presidential candidates have a variety of plans to rein in costs and improve coverage, from a new government plan for a small number of Americans to a giant “Medicare for all” program that would cover everybody and eliminate private insurance.

The Center for a Responsible Federal Budget recently analyzed four different plans, and the found the one supported by former South Bend, Indiana mayor Pete Buttigieg to be the most fiscally responsible. It would save the government $45 billion per year, on net, while plans supported by Joe Biden, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren would each leave a sizable budget hole. Part of the problem is that candidates are reluctant to fully spell out the new taxes needed to cover such a big hike in federal spending.

Penn Wharton recently analyzed the Sanders Medicare for all plan, which would cover everybody, including 30 million Americans who currently have no insurance. The Sanders plan would lower the portion of seriously ill Americans from 15% to 13% and extend U.S. life expectancy by two years. That’s obviously good.

But the Sanders plan would also require trillions of dollars in new federal spending and be economically damaging if financed the wrong way. If paid for with payroll taxes that fall heaviest on the wealthy, it would cut GDP by 15% in 2060—a huge hit that makes this method politically implausible. But if financed by the equivalent of premium payments from everybody covered, it could boost economic output slightly.

Transitioning to Medicare for all would be massively disruptive, however, with insurers that employ millions shutting down and the whole health care system adjusting to a new payment structure that could drive some providers out of business. If it ever happens, it would have to phase in slowly and predictably. Maybe a 40-year timeframe is about right.

Rick Newman is the author of four books, including “Rebounders: How Winners Pivot from Setback to Success.” Follow him on Twitter: @rickjnewman. Confidential tip line: rickjnewman@yahoo.com. Encrypted communication available. Click here to get Rick’s stories by email.

Read more:

Read the latest financial and business news from Yahoo Finance

Follow Yahoo Finance on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flipboard, SmartNews, LinkedIn, YouTube, and reddit.