Modern Value Investing: Margin of Safety Extras

- By Robert Abbott

Sven Carlin continued his exploration of margin of safety with two more tools in chapter six of "Modern Value Investing: 25 Tools to Invest With a Margin of Safety in Today's Financial Environment."

Tool 10: Cash per share or net cash per share

Carlin began this chapter with this challenging thought: "Cash is the easiest way to determine a margin of safety." By that, he meant there are times when the price of a stock is below the net cash per share. And, that is not uncommon because when there is enough selling pressure on a sector, an individual stock within it may trade at an artificially low price.

Warning! GuruFocus has detected 3 Warning Sign with AAPL. Click here to check it out.

The intrinsic value of AAPL

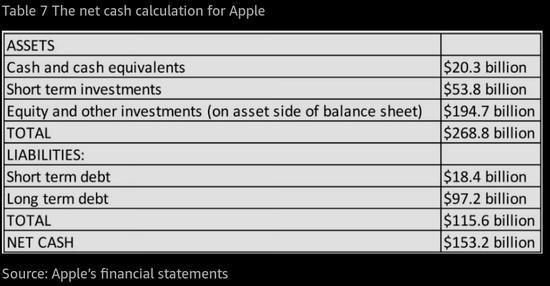

To calculate net cash per share, deduct total debt from cash and cash equivalents (the latter being anything that can converted to cash quite quickly. Carlin put data from Apple (AAPL)'s third quarter of 2017 into this table to show the calculations for net cash:

To arrive at net cash per share, simply divide the net cash by the number of outstanding shares. For that quarter, Apple had $153.2 billion in cash, which is then divided by 5.2 billion shares. That works out to $29.46 per share; Carlin next used the 2016 stock price (perhaps the average for that year, or maybe just a typo) of $90. Deducting $29.46 from $90 provides an "actual" stock price of $60.54.

But investors have to consider all stocks on their individual merits. A company that is not profitable will drain cash in the future. That's particularly true of growth and biotech companies that may be profitable but still burn lots of cash in coming years. In addition, these and young companies may have large cash balances after capitalization rounds but will tear through it, so the stock price is not cheap, despite appearances.

Here's what Carlin did like: "The time to buy stocks trading below net cash value is in market downturns when pessimism surrounding the whole market creates high selling pressure and pulls all stock prices down. A combination of 1) sound fundamentals, 2) a business that operates profitably, 3) low debt, and 4) more cash than the market capitalization is the ultimate margin of safety investment."

Tool 11: The sustainability of dividends

While it is possible to find good businesses that have cash, the only time they are widely available at good prices is during recessions. So, what Carlin called a "more applicable exercise" is to review the sustainability of the dividend, given cash on hand and cash flow, to establish a margin of safety.

Carlin added, "One of the worst things that can happen to a stock is a dividend cut." Such a move hurts the price since many investors were attracted to those stocks because of the dividend. Consequently, if dividend payments are reduced or cut, investors may sell and buy another stock. That happens even though it may be a counterproductive move by the investor. What's more, a lower or no dividend at all may also turn off potential new investors, as well as disable dividend reinvestment plans.

For an example, the author turned to General Electric (GE), which has cut its dividend twice in the past decade. The first occurred on Feb. 27, 2009, when management announced the dividend would be cut from 31 cents to 10 cents per quarter. The stock dropped 37% in the following week, and although it later recovered, the response shows how much impact a dividend cut can have.

The second occasion was on Nov. 13, 2017, when GE cut the dividend from 24 cents to 12 cents per quarter. Although the idea was to make the company more stable, the stock price became less stable, dropping 8% on the announcement day alone. Year to date, the company had seen its stock price drop 44%, so this dividend cut was not unexpected.

For Carlin, this underlined the importance of dividend sustainability when dividends are being used to establish a margin of safety. To assess that sustainability, he recommended checking a company's current profit margins and asking how they would be affected by a recession or cyclical dip. To do that, investors can check to see how margins fared during previous downturns. If the margins became smaller and were attacked by competitors, then obviously there was no certainty and dividends should not be used to assess margin of safety. On the other hand, strong companies with moats and little exposure to economic cycles would be considered safe.

As for cash held on the balance sheet, investors must ask about management's intentions. If management plans to spend the money on acquisitions or expensive buybacks, then the cash cannot be used as a margin of safety. To get a sense of management's intentions, it is necessary to get to know the company and the sector well.

Finally, Carlin reminded investors that liquidation value is the ultimate margin of safety, and if liquidation value is above the current stock price, then that provides the margin of safety. Be cautious, though, because assets are rarely sold at face value when liquidation occurs.

(This article is one in a series of chapter-by-chapter digests. To read more, and digests of other important investing books, go to this page.)

Disclosure: I do not own shares in any company listed, and do not expect to buy any in the next 72 hours.

This article first appeared on GuruFocus.

Warning! GuruFocus has detected 3 Warning Sign with AAPL. Click here to check it out.

The intrinsic value of AAPL