Rare earths mining is taking center stage in Greenland’s snap election

Arguably, rare earths triggered Greenland’s upcoming election.

The previous coalition government collapsed in February over disagreements about a proposed major rare earths mining project in south Greenland. Now the vote on April 6 will determine its fate.

On one side, the project’s advocates see it as key to greater financial independence for the autonomous Danish territory, while critics view it as a threat to an environment that’s already confronting the dire effects of a warming climate, and to a fledgling tourism industry.

The direction a new government takes will have far-reaching implications not only for Greenland’s economy, but also the global rare earth supply chain, and China’s dominance over the critical minerals used in products like smartphones and cars.

“It’s the most important issue in the election,” said Javier Arnaut, assistant professor of economics at the University of Greenland.

One of the world’s largest rare earth deposits

At the heart of contention is the Kvanefjeld project, a rare earths and uranium project known locally as Kuannersuit. The project is owned by the Australian company Greenland Minerals, which has promoted it as having the potential to become “the most significant western world producer of rare earths,” and possibly at some of the lowest costs globally (pdf), too.

Greenland Minerals’ efforts to bring Kvanefjeld into full operation dates back more than a decade. It began several years of extensive drilling and research in 2007, followed by various feasibility studies and environmental and social impact assessments that are key requirements for obtaining permits from the Greenland government. One of the final regulatory steps was to hold a public consultation, but the coronavirus pandemic and the collapse of the coalition government has caused delays.

The fate of Kvanefjeld now hangs in the balance, and Greenland Minerals is well aware that its business operations hinge on how the country’s population of 56,000 cast their votes. The outcome is important to China too—Greenland Minerals is roughly one-tenth owned by Shenghe Resources, a Chinese rare earths giant with close ties to the Chinese government.

The Inuit Ataqatigiit (IA) party, which has led in opinion polls, has said it will scrap the rare earths project altogether if it wins a majority of parliament’s 31 seats.

Proponents of the mine say Kvanefjeld would represent a significant source of revenue for Greenland. That would help to diversify an economy that is overwhelmingly dependent on fisheries and funding from the Danish government.

“Some argue that mining is an important aspect in Greenland’s independence project,” said Marc Lanteigne, professor of political science at the Arctic University of Norway, because the extra income would help offset the loss of the annual subsidy that Greenland currently receives from Denmark. The subsidy, known as a block grant, accounted for nearly 30% of Greenland’s GDP in 2018, according to government statistics (pdf).

Those opposed to Kvanefjeld express concerns over the potential environmental damage caused by the extractive industry, as well as possible impacts on conventional ways of life and an influx of foreign workers disturbing the “cohesion of the community” in Narsaq, the town closest to the mine, said Mingming Shi, associate editor for Arctic news site Over the Circle.

But axing a project at such a late stage, and in which Greenland Minerals has invested significant time and money, could shake investor confidence in Greenland’s mining industry.

“It would be difficult for foreign investors to anticipate the policy of the extraction industry of Greenland, given high startup costs of a mine,” said Shi.

China looms large

Hanging over the issue of Kvanefjeld is a giant with ambitions to expand its influence in the Arctic region: China.

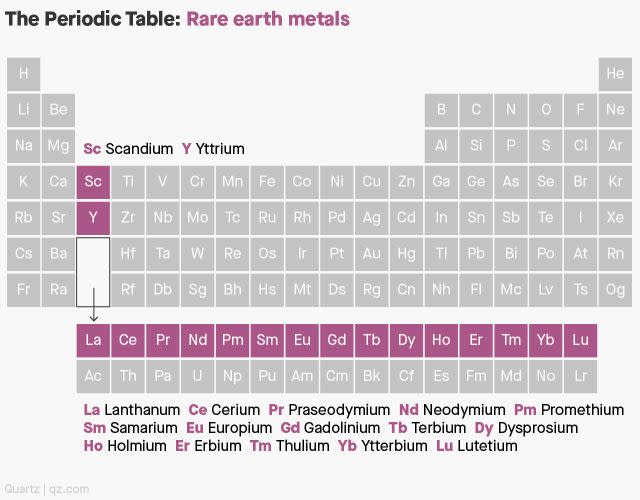

Rare earths, critical inputs to electric vehicle batteries and military equipment, hold national security importance, and major countries including the US and Australia are working to limit their reliance on China for the metals. Kvanefjeld, as one of the largest rare earth deposits, could prove a significant supplier of the critical raw materials.

“For Greenland, it would be a geopolitical tool to…control these resources, and also to use Denmark and the United States as potential buyers of this resource,” said Arnaut, from the University of Greenland. “It would represent an important step to be a real political player in natural resources.”

But the existence of giant rare earth reserves alone does not make a mining operation economy viable, nor does it immediately reduce the risks of dependency on China to European or US supplies of rare earths, note the authors of a recent policy brief on Greenland’s rare earths industry by the Danish Institute for International Studies.

That’s in large part due to China’s dominance in rare earth processing, a key step in the supply chain that turns raw ores into separated high-purity rare earth metals for high-tech applications. There is currently only one rare earth processing facility of scale outside of China, owned by the Australian firm Lynas and located in Malaysia. In many cases, note the authors, this means new rare earth mining projects are dependent on long-term contracts with Chinese firms that purchase the rare earth ores for processing in China.

In fact, far from shaking China’s grip on the global rare earths industry, one of the proposed ways (pdf) of operating the Kvanefjeld project—with the Chinese minority owner Shenghe importing raw materials to China for processing—might actually help reinforce China’s dominance in rare earths processing, said Per Kalvig, chief consultant at the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland.

“The Chinese tariffs system actually favors imports of the raw materials, not the separated goods,” said Kalvig, who co-authored the policy brief.

Importing raw rare earth materials from a a foreign mine—the same as what Shenghe is doing in its joint venture with US miner MP Materials’ Mountain Pass mine in California—”may suit very well the Chinese strategy,” giving China greater control over the high value-add segment of the supply chain just as competition is increasing from foreign separation plants that are beginning to ramp up operations, said Kalvig.

Greenland could be key to China’s Arctic ambitions

Beyond this particular mining project, China also has key strategic interests in developing business ties with Greenland.

“China’s interest in Greenland is beyond economic cooperation, but also expanding its Arctic profile as a stakeholder and partner, such as in climate change,” said Shi, adding that China’s involvement in the Kvanefjeld project provides an excellent opportunity to demonstrate how it can contribute to the economy of Greenland and the wider region.

Even more important for China is Greenland’s role in its Polar Silk Road strategy, a plan to grow its economic and diplomatic footprint in the Arctic. Greenland, Lanteigne, the Arctic University professor, recently wrote in The Diplomat, may become a “make-or-break component of the Polar Silk Road, given Chinese mining interests in the territory.”

Other countries have significant business interests in Greenland too, including the UK, Canada, and Australia.

“China has a growing footprint, but not the biggest one yet. My concern is with the Western obsession with China, we are overlooking the opportunities with the assets we hold in Greenland and the alliances that will come to bear,” said Dwayne Menezes, managing director of the Polar Research and Policy Initiative and author of a recent report calling for a Five Eyes critical minerals alliance centered around Greenland. (The Five Eyes is an intelligence alliance between Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the US, and UK.)

Nevertheless, an independent Greenland—something a majority of Greenlanders want, and which a pro-independence government could hasten—would mean a need to develop business relations with more countries. That’s something that Beijing wants to capitalize on.

“So for China to establish its role there as a necessary partner…being there is considered very crucial,” said Lanteigne.

Sign up for the Quartz Daily Brief, our free daily newsletter with the world’s most important and interesting news.

More stories from Quartz: