Wendy Goodman Recalls the Long Island Home That Sparked Her Lifelong Love of Design

It was Camelot before Camelot. Sands Point, just a 40-minute drive from New York City on a good day, so close and yet a world away on the Cow Neck Peninsula in Nassau County, surrounded by water and bordered by sandy beaches. It’s where Guggenheims, Vanderbilts, and Goulds bought land and built castles-and, some say, it was the model for East Egg in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby.

But there was also a more down-to-earth aspect to life in Sands Point-one in which politicians, writers, artists, and theater professionals took retreat in the private oases provided by their hosts. That’s the Sands Point I remember from my childhood summers there, spent in a bathing suit at our two-story shingled house next door to Marie and W. Averell Harriman’s compound overlooking the Long Island Sound.

Memories of the Harrimans

It was the 1950s, a time as far away from the present as can be imagined, when as governor of New York State from 1955 to 1959, Averell had a state trooper as his security detail, and that was all. My sister Tonne and I would sit at the end of our driveway waiting for the arrival of Pam and Alida Morgan, our summer “sisters,” who would come for two weeks every year to visit their grandparents, the Harrimans. Tonne and I had the ritual down: We’d sit on the hot tar surface, oblivious to the heat and discomfort, at the exact point where we could see the car that had been sent to pick up our friends at the airport as it cleared the trees in the bend of the road.

The arrival of Pam and Alida was the highlight of our summer. Averell had sold our father two acres of beachfront property next door to his in 1954. His property stretched all the way from the main road to the beach and along the coast up to the Herbert Bayard Swope house on the point. (The press baron’s 25-room Lands End, where he held lavish all-nighters, was the alleged model for Gatsby’s parties.)

Our parents had built a modest home with a screened-in porch and a playroom with doors opening onto the lawn. This led to the beach where Tonne and I spent most of our time with our younger brother, Ed, and sister Stacy.

From the window of time we spent with Pam and Alida, we learned that they led unimaginably exotic lives. They called their maternal grandmother grand-mère, as they were born in Paris and spoke French before they learned English. Averell, their step-grandfather, was known to them as Ave.

Their time in Sands Point was bookended by a trip to the Adirondacks to see an army of cousins we deeply resented, as we never wanted the girls to leave. But once the car rounded that bend, nothing else mattered; together, we became the inseparable four musketeers and had the run of the Harriman house. Through a swinging door off the living room, we’d race to the forbidden kitchen quarters, where Jeanne the cook would have made a fresh batch of her meringues just for us. But manners were always on call; we had to ask permission from Jeanne to enter her realm. And nothing tasted quite as delicious as the super-salty Fritos we’d poach from glass bowls on the bar of the porch where the grown-ups had cocktails, followed by dinner over a mirrored table that ran the length of the room.

Design Details

The daily ritual of saying a proper good morning to Mrs. Harriman, who would not emerge from her bedroom until early afternoon, meant that we were allowed into her sanctuary. From the sitting room, you could see to the end of the corridor, where her bedroom was cordoned off not by a door but an upholstered fabric screen. Its presence teased you into thinking that you might spy the chamber behind it if you stood at a certain angle, but of course that would never happen unless you came all the way around the screen.

It was a clever design device, a courtesy to her guests, who instead of a closed door would see the lovely pomegranate-patterned fabric panels illuminated by the natural light off the Long Island Sound-such was the degree of her thoughtfulness. The screen also established her personal space in the midst of a house where friends constantly filled the compound’s guest wing to capacity.

The bedroom was her haven-and the most beautiful, unpretentious, and luxurious one I had ever seen. It wasn’t lavish, but it was perfection, filled with the salt air that blew through sheer curtains beneath formal drapes. The space was designed by George Stacey, the decorator-“Ave called him Secretary of the Interior,” Alida told me-who also designed the family’s New York townhouse on East 81st Street, where the treasury of their paintings lived, most of which now reside in the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C.

The curtains, the screen, and the upholstered headboard were all done in the same blue-and-white print, which Alida muses could have been from Clarence House, as there are no photographs of the home to reference, none at all. Memory is the only way to conjure up images of the silky elegance of this room.

Averell had a separate, much smaller bedroom next door to Marie’s in an arrangement that was de rigueur in so many households back in the 1950s, especially as Averell worked late nights. But Mrs. Harriman’s bedroom was all the more impressive because she presided in it from her bed in a quilted satin bed jacket, her black hair immaculate, her lipstick always fresh. That was her uniform, if you will, working from her command post where she read mail, planned menus, and made calls from a big white telephone on the bed next to a white wicker breakfast tray, placed over her legs, with large pockets on either side holding the day’s newspapers and magazines. Her two wirehaired dachshunds, Dini and Gary Cooper, were always nearby in their regular spots on the blue-and-white floral D. Porthault bedding, and occasionally Averell’s white Labrador, Brumie, would wander in and plunk down on the cotton rag rug that felt so good under bare feet.

Mrs. Harriman had a deep, rich voice that greeted but never indulged us. She treated us not like adults, but not how other grown-ups we knew treated children. I wished we could amuse her and make her laugh. In my childhood mind, I understood that her bedroom was more glamorous than any place I had ever before experienced. The glamour came from the idea of retreat-that a room could be yours alone for you to savor, or to share, but by invitation only. It was my first glimpse into the world of grown-ups, where glamour and privacy ruled as one.

Curb Appeal

The private road that led to the Harrimans’ estate had two entrances. Each took you on a different path through a magnificent forest of old trees down to the water. One entrance had massive, old wrought-iron gates, and the other had a few mailboxes marking the drive. The latter was the one guests and dignitaries took to the Harriman residence, and had you not known its exact location, you might have driven past the single-story bungalow partially hidden by boxwood and rose hip bushes.

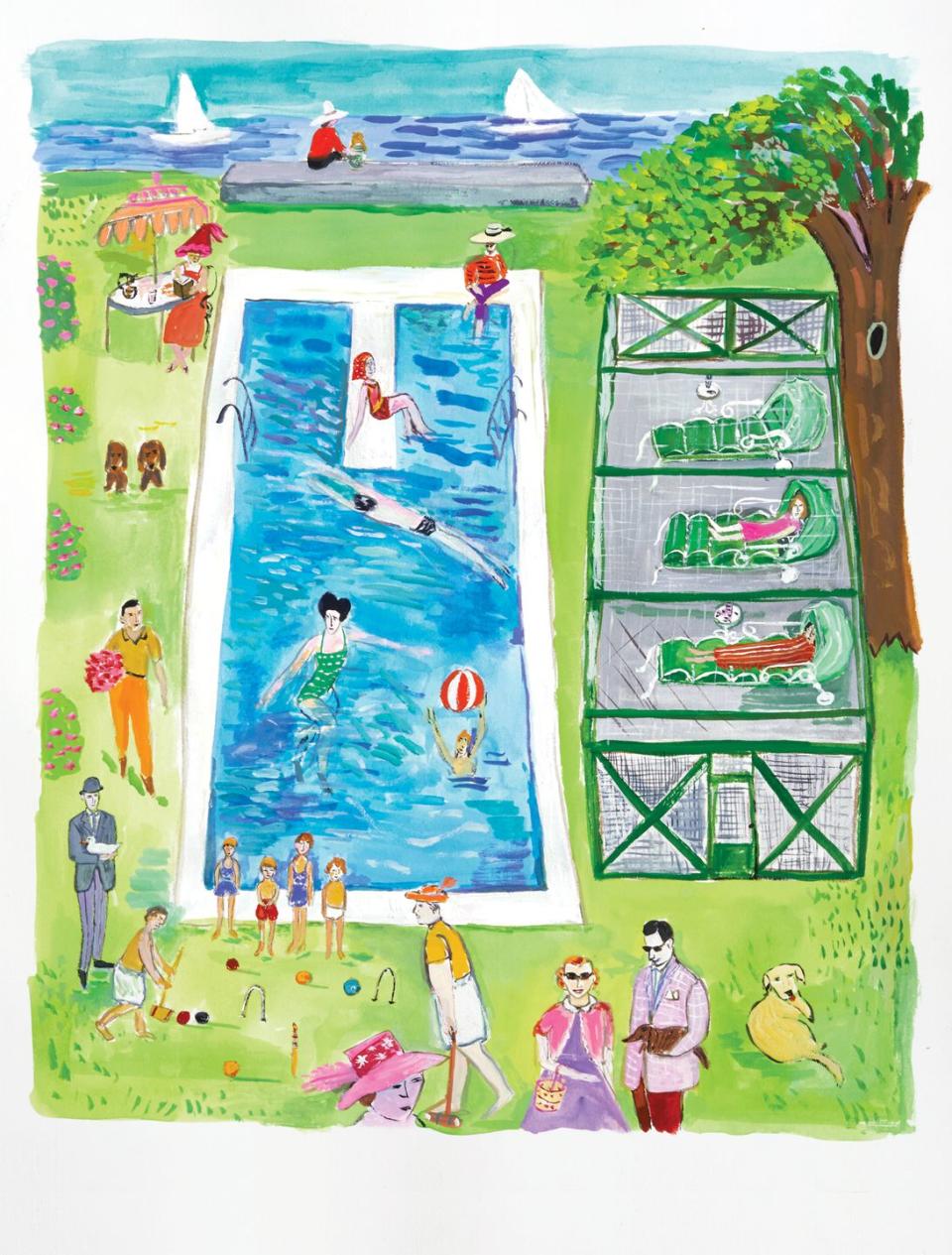

But the site was extraordinary, and the drive down from this unassuming entry had a point at which you almost had to stop the car to catch your breath and take in the majesty of the view. From here, one could look beyond the rolling lawn that descended to the beach and see Long Island Sound dotted with sailboats. The paved surface of the road then changed over to sand-colored pebbles that made a distinct crunching sound as cars passed over them. No one was going to make a noiseless entrance as they approached the house, not even on foot.

The original house built on this sprawling waterfront property started out as a kind of way station-a convenient spot where Averell could change his clothes after a game of polo at the nearby Meadow Brook Club. Peter Duchin, son of bandleader Eddy Duchin, who was raised by Marie and Averell after his mother’s death in 1937, told me this story: “After Ave built the house, he had a yacht, The Spindrift. Every morning, he would wake up, walk to the pier in his bathrobe, and board the yacht, be shaved and dressed by his valet, read the papers, and be deposited at his office on Wall Street.”

By the time Averell was elected governor in 1954, a guest wing, tennis court, and saltwater swimming pool had been added to the property, plus what looked like a child’s playhouse near the caretaker’s quarters but was actually a one-room security station for the state troopers on duty 24/7 to protect him. There was also a small screened-in pavilion beside the pool. We called it the Bug House. It was large enough to hold three white-painted iron chaise longues topped with comfy cushions upholstered in a green sailcloth and giant collapsible hoods that could be raised to shield the seats’ inhabitants from the sun.

The long rectangular saltwater pool, embedded in the lush carpet of lawn near one side of the house, was recessed in a white-painted cement border with drains to capture the runoff. When you were in the pool gazing out on the sound, the effect was not unlike what is now known as an infinity pool. Back then, however, I’m pretty sure it was just a happy coincidence: The pool had to be close to the beach because a big pipe conveyed salt water from the sound directly into it.

The Social Scene

The social life of Sands Point happened around that pool, and the best part of the day was being allowed to walk across the vast lawn and jump into that exotic body of water. A great ceremony was made of the arrival of Marie Harriman’s mother, Beulah (Pam and Alida called her Gram Norton), and her sister, Rose, who had flaming-red hair that contrasted with Gram’s frothy nimbus of silver waves. We would watch, transfixed, as they would tuck their respective coifs under white bathing caps before taking turns doing swan dives off the diving board into the pool. The two were well into their 90s when these feats occurred. Pam and Alida wore proper matching bathing suits with skirts that Tonne and I, clad in our unisex bathing trunks, thought very fancy.

Pam and Alida would venture into the Bug House to greet their grand-mère while we waited outside-well aware that the door had to be opened and closed very quickly or else the whole point of the shelter would be lost, if so much as a single annoying insect succeeded in entering. Mrs. Harriman’s best friends, Ginny Chambers and Madeline Sherwood (who was married to the great playwright Robert Emmet Sherwood), would spend hours in the Bug House reading and filling out crossword puzzles. But the men rarely ventured inside, as they were all too busy playing very serious rounds of croquet on the stretch of lawn off to the left of the pool near the tennis court.

The men’s attire for these fiercely competitive games was baggy linen shorts and no shirts. Robert Sherwood would usually opt out, preferring to sit on the dock in a wooden rocking chair instead. “Occasionally, if the tide was right,” Duchin recalls, “I would go fishing for stripers with Mr. Philips, the caretaker, who would row as I would trail a spinner with a sandworm attached.”

Time spent in Sands Point meant the freedom of days under the sun by the water, and as if that wasn’t wonderful enough, we anticipated the arrival of our summer sisters with excitement and joy every year for at least a decade. It is no wonder that Pam and Alida have gone on to become lifelong friends, and that Peter Duchin continues, to this day, to act as our spirit guide.

This story originally appears in the June 2019 issue of ELLE Decor. SUBSCRIBE

('You Might Also Like',)