In 40 years as a founder-CEO, Michael Dell turned his dorm-room PC company into a tech giant. Can he cash in on the AI boom?

It’s hard to get a splashy sound bite out of Michael Dell, even if you tee him up for one. When asked how big a growth opportunity the AI wave could be for his namesake company, Dell Technologies, the founder and longtime chief executive doesn’t offer up any pithy one-liners but instead ruminates in real time.

“It feels every bit as big as previous waves, but probably bigger,” he says, pondering the question, and then adds, “You know, maybe quite a bit bigger.” He takes another brief pause, reconsiders his own words, and delivers a most inconclusive conclusion: “I don’t know for sure. Nobody knows.”

We’re seated in a conference room at Dell Technologies’ headquarters just outside Austin, where the temperature has hit 88° F in early March. Dressed in dark slacks and a navy blue denim button-down (Texan for business casual, no matter the season), Dell has just emerged from a photo shoot that he tolerated but clearly didn’t relish. It’s not that he isn’t on board with being the name and face of his company. That’s been true for a while—40 years, to be exact. He remains Dell Technologies’ biggest believer—and biggest shareholder, with 53% of the $79 billion company’s stock under his or his wife Susan’s name. But he’s not a natural-born showman. Never was. In fact, he seems to go out of his way to not put on a performance—even as he’s embarking on what could be his greatest act yet.

Unlike some other tech CEOs, Dell doesn’t do bombastic declarations or colorful antics; he doesn’t have a side hustle that involves blasting himself into outer space. Despite having spent his entire adult life in the public eye, he is measured, analytical, and almost intentionally unexciting. So his reluctance to put a ceiling, or even a floor, on what generative AI could mean for his company is not surprising.

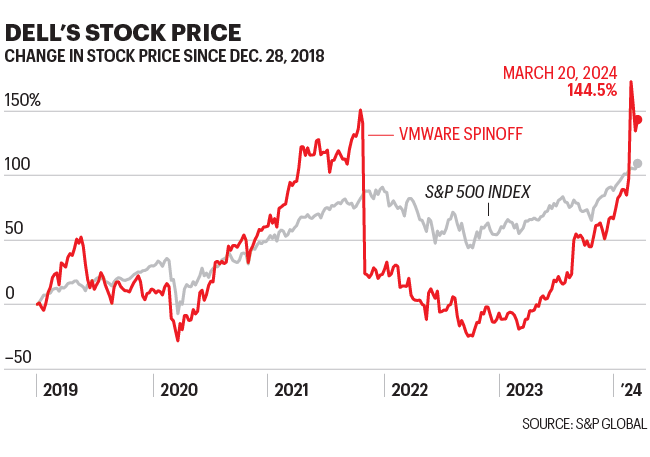

But while Dell may prefer to hedge, the market isn’t hiding its exuberance. Just a few days before our interview, on March 1, Dell Technologies’ share price leaped 38%, hitting an all-time high above $131 after the company reported earnings that beat analyst expectations. The announcement generated plenty of excitement about demand for Dell’s growing portfolio of back-end tech products, the kind required for storing and managing the massive datasets needed to run—you guessed it—generative AI applications. Orders for AI-optimized servers were up 40% in the most recent quarter. As chief operating officer Jeff Clarke said in the company’s earnings release, “We’ve just started to touch the AI opportunities ahead of us.”

It’s not just Dell’s company that’s been buoyed by the buzz. As a result of the massive rise in the stock, Michael Dell’s personal net worth reportedly hit the $100 billion mark in early March—a notable milestone even for a man who became a billionaire at the tender age of 30.

But none of this seems to rock Dell’s world. Over the decades, he’s maintained the same steady demeanor through exhilarating highs and harrowing lows. Along the way, he’s steered his company through multiple major pivots. And he’s showed an uncanny ability to read his customers’ needs and make the right strategic change at the right time, whether de-emphasizing PCs in favor of servers, sensors, and storage, or taking the company private—over the heated opposition of Carl Icahn—in a mammoth buyout.

That privatization maneuver is precisely what positioned the company to capitalize on the current AI boom. Over the five years that it was privately held, Dell was able to truly diversify from selling laptops and desktops. Away from the market’s obsession with quarterly earnings, Dell consolidated and expanded his company, creating a behemoth provider of infrastructure tools for corporate customers. Along the way, he engineered what was then the biggest tech deal in history, the $67 billion acquisition of data storage provider EMC.

If Dell isn’t a dynamic, headline-making speaker, it may be because he’s built this four-decade run on listening—deploying his analytical skills and deep curiosity to recognize what his customers need and to navigate his industry’s twists and turns. “I love spending time on the technology, and I love spending time with our customers,” he tells me. And at least where business is concerned, he adds, “I don’t really love anything else.”

Dell Technologies still sells Dell PCs; in fact, computers make up the majority of its revenue. But today it’s a company vastly different from what it was five or 10 years ago—let alone 40. The one constant? Dell himself. “This is probably the longest-sitting CEO in the tech industry,” says Marc Benioff, cofounder and CEO of enterprise-software maker Salesforce and a longtime friend. “He’s six months younger than I am, but I view him as an older brother,” Benioff says of Dell. “He’s a phenomenon in every possible way.”

Sitting across from Dell at his HQ in Round Rock, a corporate campus that’s forgettable except for its sheer size, “phenomenon” isn’t the first word that comes to mind. But Dell has built—and hung on to—an empire that now provides the technological building blocks for 99% of Fortune 500 companies, most of which will have new needs in this new era of AI. If he plays his cards right, the next chapter of the story could make both the CEO and his once-flailing PC maker more relevant than ever, all but ensuring he’ll stay at the helm for years to come.

The morning after our interview, Dell is speaking on a panel at a health care innovation summit at the University of Texas at Austin, his alma mater. (Dell finished two semesters before dropping out to devote himself to selling PCs full-time.) Investor Jim Breyer, who relocated to Austin from Silicon Valley in 2019 at the Dells’ suggestion, introduces the CEO with glowing superlatives. “Michael Dell is the most courageous entrepreneur I’ve ever worked with,” he gushes.

Dell’s performance is … just fine. (It’s clear that public speaking is not his happy place.) Still, he comes across as confident and purposeful. At 59, Dell retains a youthful bearing, his curly hair only tinged by gray. And from the audience reaction, it’s clear Dell’s the big man on campus, even if he never graduated.

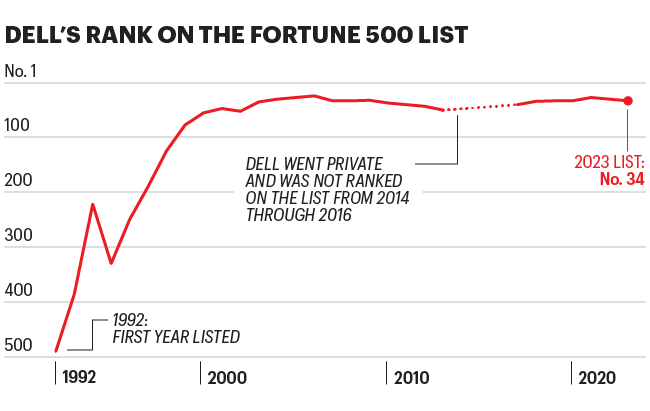

In his well-documented early days, the nerdy but gutsy founder could seemingly do no wrong. In 1984, as a premed freshman, he started tinkering with computers in his UT dorm room. By age 19, he had left school and turned all of his attention to his business. He faced other, much bigger competitors, including IBM and Apple. But Dell pioneered a new way of doing business: His computers were built to order, and he sold them directly to consumers, cutting out the middleman. In 1988 he took Dell Computer public, raising $30 million and using the capital to expand globally. At age 27, he became the youngest CEO on the Fortune 500. And the company just kept growing—as long as demand for PCs was on the rise.

But PCs would prove to be the company’s Achilles’ heel. In 2001, Dell became the world’s leading computer maker, surpassing the once-mighty Compaq. But sales soon began to decline. Asian manufacturers had entered the fray, offering cheaper products to American consumers. And by the late 2000s, smartphones and tablets had swarmed the market, slowing demand for desktops and laptops even more. The company tried to jump on the mobile bandwagon, but its efforts were ill-received: Dell’s “phablet,” a product that sat in the unnecessary purgatory between a phone and a tablet, was discontinued after just one year.

By then, Dell had been trying for years to diversify. In 1995 he entered the server market with the PowerEdge, a product line that still exists—designed for enterprises that were amassing far more data than they could manage with their existing equipment. In 2006, the company launched a business unit to support cloud computing, including tools to power “hybrid clouds”—private clouds (which keep data on a customer’s premises) that can integrate with public ones (where data is hosted by a third party).

But this expansion wasn’t happening fast enough to offset declines in PC sales, and investors hammered Dell’s shares. In 2013, after more than two years of falling PC revenue (and after the stock price bottomed at under $11), Dell decided to take his baby private—hypothesizing that shielding the company from Wall Street’s short-term focus on profitability was the best way to reset for the long term.

Benioff refers to the deal as Dell’s “magic trick.” But the maneuver was anything but slick and graceful. “I had no idea how difficult it was going to be,” Dell recalls. “When it started, [I thought], ‘Is this like a one-week thing or two-week thing?’ I didn’t know it was going to be an eight-month thing.”

Dell wasn’t in it alone. Egon Durban, co-CEO of private equity firm Silver Lake, was his partner from the get-go. The two presented Dell shareholders with what they thought was a good offer, a $24.4 billion deal financed by a mix of equity and debt—the largest leveraged buyout in tech-industry history. But then corporate raider Carl Icahn entered the picture, snapping up a sizable chunk of the company’s shares and agitating for a more generous offer. Before they knew it, Dell and Durban were going to war, fighting Icahn as he made a counteroffer that involved buying the company himself—and ousting Dell as CEO.

Eventually, Icahn got concessions, and Dell got his deal. Dell and Durban increased their offer by 10 cents a share and threw in a special dividend for some shareholders. And on Oct. 29, 2013, Dell Computer became a privately held company, owned by Michael Dell and Silver Lake.

During the lengthy feud, the antagonists stayed true to their personalities: Icahn took to CNBC and other outlets to spread his narrative, while Dell lay low. But in recent years, Dell has spoken openly about the clash. His 2021 memoir, Play Nice But Win, opens with a scene in which Dell goes to Icahn’s house for a dinner of mediocre meatloaf, in a (failed) attempt to find common ground. Though Dell says he doesn’t hold grudges, he also says he felt a need to “expose” Icahn’s tactics.

More than 10 years later, it’s clear there’s no love lost between them. “Icahn showing up was the hardest part,” Dell says. “It was a long, painful period where everyone was subjected to this horrible situation.” Dell maintains that Icahn never really planned to buy his company but simply wanted to squeeze more out of the deal. For his part, Icahn, in a phone interview, says that his actions forced a “meaningful improvement” of the buyout. “The shareholders got a lot more money because of me,” says Icahn.

Tellingly, both men quote World War II–era leaders to describe their conflict. “What’s that Winston Churchill quote?” Dell asks me rhetorically, invoking the former British prime minister: “If you’re going through hell, keep going.” Icahn, meanwhile, puts his own paraphrasing spin on a 1936 campaign speech by Franklin D. Roosevelt: “Dell hates me—and I welcome his hatred.”

Still, the trials arguably made Dell a better leader. Those close to the CEO say that his determination and belief in the deal carried the enterprise through a rough patch. “Relationships are forged on the battlefield,” says Durban, who remains close to Dell and whose firm is one of the company’s largest shareholders. Employees from that era say Dell became more connected than ever to his workforce, and even better about communication with the rank and file.

Just as important, Dell proved himself to a wider swath of the business world as an analytical, decisive chief executive. “He took a large risk, which is easier not to do,” Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JPMorgan Chase, says of Dell’s deal. “But he stuck to his guns.” Describing Dell, Dimon invokes the “OODA loop,” a military acronym for efficient decision-making that he says is a secret sauce for the tech CEO. (OODA stands for “observe, orient, decide, act.”)

That kind of coolheadedness also characterizes Dell’s very, very few hobbies. Benioff tells me that his friend recently took up hunting with a bow and arrow. (Dell’s company won’t confirm this.) Dell hunts for birds, Benioff says—the kind of elusive target you can hit only when you’re calm, unemotional, and utterly focused.

Jeff Clarke, Dell Technologies’ COO, is the closest person Michael Dell has to a cofounder, having joined his team in 1987. Speaking to Fortune via videoconference, Clarke—dressed in a red, white, and blue T-shirt that simply says “TEXAS”—refers to the company’s private-company era as one of the most fun periods of his career. “It was liberating,” says Clarke.

Being out of the public market meant that Dell could make big bets and invest in R&D, even if the payoff wasn’t immediate. The company could rebuild itself around providing all things infrastructure for corporate customers like Home Depot and CVS Health, whose greatest needs increasingly revolved around the growing mountains of data they were accumulating. In 2016, Dell and Durban—with Dimon’s help—orchestrated another financial feat, the $67 billion purchase of EMC and its software subsidiary VMware. The acquisition was “something we had dreamed about doing,” Dell says.

Still, the deal was an expensive bet that saddled the business with a heavy debt load—and it created hassles down the road. The merged company started trading publicly again under a share class that tracked its ownership interest in VMware; two years later, it bought those shares back and replaced them with a new share class. Along the way, some VMware investors (including, briefly, Dell’s old buddy Icahn) sued, arguing that the complex deal undervalued their shares, and Dell Technologies eventually paid a $1 billion settlement. Still, the acquisition added an even broader data-storage and management portfolio to Dell’s arsenal, making the company indisputably stronger.

Dell’s company has never been a “market maker,” a company that creates demand for something that didn’t previously exist. But it hasn’t had to be. “What Dell’s been good at is knowing the right time to get into a market,” says Patrick Moorhead, an analyst who has covered Dell and its competitors for years and now runs Moor Insights & Strategy. “They’re so close to their customers that they just know.”

That closeness was embedded at Dell from the earliest days, when Michael Dell himself was building PCs for one customer at a time. In 1988 Dell wrote the company’s first Culture Code, with “Provide high-quality products and excellent customer service” at the top of the list. His focus hasn’t changed much, his allies say, and it’s been central to his ability to keep transforming the company.

On Dec. 28, 2018, the reorganized, renamed Dell Technologies emerged fully from its cocoon, trading on the NYSE under a new share class. In its metamorphosis, the company had all but shed its image as a lagging PC maker, refashioning itself as an enterprise infrastructure giant. And enterprises, it turned out, were about to need a whole lot more infrastructure—and maybe, just maybe, more PCs.

Back in Round Rock, Dell is trying to explain what an “AI PC” is, and why anyone would want one. “I have a list,” he says as he gets up to grab his phone from his office. The CEO comes back and proceeds to rattle off a catalog of capabilities.

There’s real-time, AI-powered translation, he explains, and a feature called “circle to search,” which enables PC users to highlight a word or line, which the computer will then provide more context and information for. There’s also “generative AI editing,” which can assist with any kind of writing or content creation. What customers actually end up using these machines for, Dell admits, is beyond his expertise to foresee. “But I believe that people will figure out creative uses and that companies will want to have the capability to make their people more productive.”

In fact, Dell’s lessons from its earliest days of customizing laptops still apply in the AI era: The key is to be flexible enough to meet customers’ demands. “The competitive advantage for Dell today is that it offers services you can tailor to almost every need in AI,” says Orit Gadiesh, the chairman of Bain & Co. and a decades-long consultant and confidante of Dell’s. “It’s not a fixed thing.”

Corporate customers in and outside tech are already clamoring for back-end machines that can both house and make sense of the data that feeds into generative AI applications. At a time when huge platform creators like OpenAI and Google are competing for corporate clients, Dell Technologies doesn’t have to worry about who wins: Its tech “stack” is agnostic to different flavors of generative AI, just as its cloud offerings have always accommodated hybrid, private, and public cloud strategies. And just as with the move to the cloud, Dell is counting on one common denominator with AI: that all companies, regardless of which AI applications they build or deploy, will want control over the hardware where the relevant data is stored.

To be sure, Dell didn’t know that the generative AI explosion would happen when it did; he credits Jeff Clarke with devising much of the company’s AI road map. But he calculated long ago that going all in on data infrastructure was the best way to position his company for the future. As a result, “he’s not just providing the picks and shovels, but also housing and food and beverages for the AI gold mine,” says Silver Lake’s Durban.

It’s still early days for Dell Technologies’ AI story. Fast as it’s growing, Dell’s AI server products account for just a tiny fraction of its business. But most financial analysts seem bullish about what’s to come. There’s even hope that the AI craze will jump-start demand for PCs—AI PCs, to be precise. The thinking is that the need for increased processing power won’t just be on the data-center side (where servers and storage systems handle companies’ information), but also on the desktops and laptops that consumers and workers interact with.

In February, Dell Technologies announced its first line of Latitude AI PCs, which look like normal computers but include a tiny component called a neural processor, the key to enabling generative AI workloads. It’s not the only vendor with high hopes in the category—HP and Lenovo have announced similar products. And it’s not clear when demand will take off. Bloomberg Intelligence analysts wrote that “sales and units shipped may disappoint investors in calendar 2024, having a greater potential impact in 2025.”

Even Dell acknowledges that spurring demand could take a while. That said, “if you’re responsible for the PCs in a company, the last thing you want to do is have a bunch of PCs that don’t do the thing that the users want them to do,” says Dell. “I do think there’s going to be a refresh wave.”

The top floor of the University of Texas’s Innovation Tower, a new high-rise that’s meant to be a startup hub, is still empty. But one only has to look out the windows for inspiration. The 360-degree views of the Austin skyline show a city dotted by cranes and construction in almost all directions.

Jay Hartzell, the university’s president, is showing me around, pointing out all of the landmarks—including the buildings adorned with the name of the institution’s most famous dropout. Michael Dell never did become a doctor, but his name is on his alma mater’s medical school, the university’s teaching hospital, and its pediatric research center. (Not to mention Austin’s Jewish Community Center.)

“When we talk about what we want to produce as a university, and why people should come here, he’s sort of Leading Exhibit A,” says Hartzell. He credits Dell not only with being a major employer of UT graduates but also with helping to spur the city’s broader tech ecosystem. Over the years, tech companies from Meta to Apple have set up shop in the Texas capital. Investors, too, from Vista Equity Partners to Pimco to Jim Breyer, have put down roots. UT recently welcomed its first cohort of students in a brand-new AI graduate degree program.

“If you’re responsible for the PCs in a company, the last thing you want to do is have a bunch of PCs that don’t do the thing that the users want them to do.”

Michael Dell

Dell, who is originally from Houston, never wanted to move his headquarters away from Texas, even when others told him he should relocate to Silicon Valley. “He helped put the place on the map,” Austin Mayor Kirk Watson tells me in a phone interview. “If you took Michael Dell out of the equation, it would be a strikingly different city.”

Dell has made his mark outside of Austin, too. The Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, which the couple founded in 1999, has 800 active projects around the world at any given time—focusing on education, training, and health innovation to help children living in poverty. (Dell and his wife recently contributed another $3.6 billion to the foundation, bringing its total endowment to $5.2 billion.) Dell says he spends a little more time each year on the foundation. He’s also gotten more hands-on with his family office, which invests in real estate development and hotel companies, among other sectors.

Could those jobs someday be his life’s work? Dell’s next chapter could be a long one: Even after 40 years leading Dell, he’s still so young, at 59. But the thought of playing any role other than his current one—at the center of the business that he’s synonymous with—seems to stump him. When asked if he could see himself running Dell Technologies in 20 years, Dell says he hasn’t thought that far ahead, but that there’s no other role he craves. Then, at long last, he provides something like a money quote: “I’ve said this before: I’ll still care about Dell when I’m gone.”

The long and winding road

Michael Dell’s company began life in 1984 as PC’s Limited—selling computers, and that’s it. A few crucial pivots helped the company evolve and stay not just relevant but dominant.

1995

Dell Computer, by then a Fortune 500 company, releases the first-generation PowerEdge enterprise server—its first attempt to sell data storage to enterprises.

2006

Dell joins the cloud era, announcing a new business unit that provides cloud products and services to customers. Demand is relatively slow to catch on.

2013

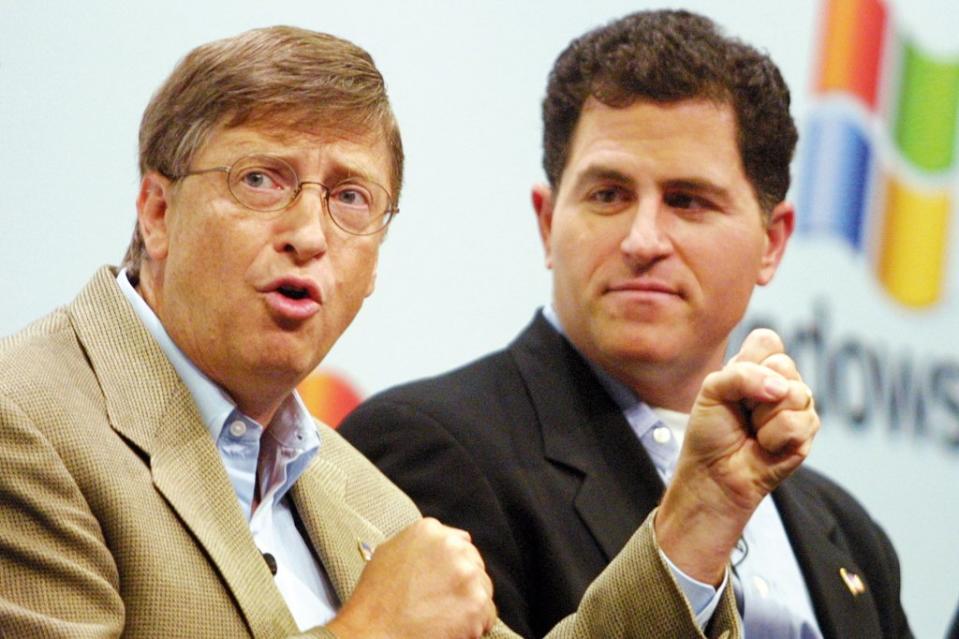

Michael Dell and Egon Durban of PE firm Silver Lake (above, with Dell at left) take the company private in an effort to refocus the company on corporations’ data infrastructure needs.

2016

Dell acquires EMC and its stake in VMware for $67 billion, at the time the largest tech deal ever—making Dell’s data-storage and management portfolio far larger.

2023

Dell Technologies releases a series of infrastructure products, including servers and storage, that are optimized for generative-AI applications.

2024

In February, the company announces its AI PC, which includes a “neural processor” to handle AI workloads. In early March, Dell Technologies stock hits an all-time high.

This article appears in the April/May 2024 issue of Fortune with the headline, "The [forever] founder."

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com