Americans should get a big pay bump, but not until 2022, analyst says

The problem of slow-rising wages for workers in the U.S. is one that has befuddled economists, including the top brass at the Federal Reserve for years. In an environment of decades low unemployment, wages should be rising more strongly than they are, according to long-held economic assumptions best illustrated by the economic model known as the Phillips curve.

But wages are about to pick up, as long as Americans can wait four years, one market strategist says.

John Herrmann, director of interest rate strategy and an economic forecaster at Mitsubishi UFJ Securities, says that this trend we have been witnessing has been distorted by the demographic challenges the U.S. faces and the slow recovery since the financial crisis.

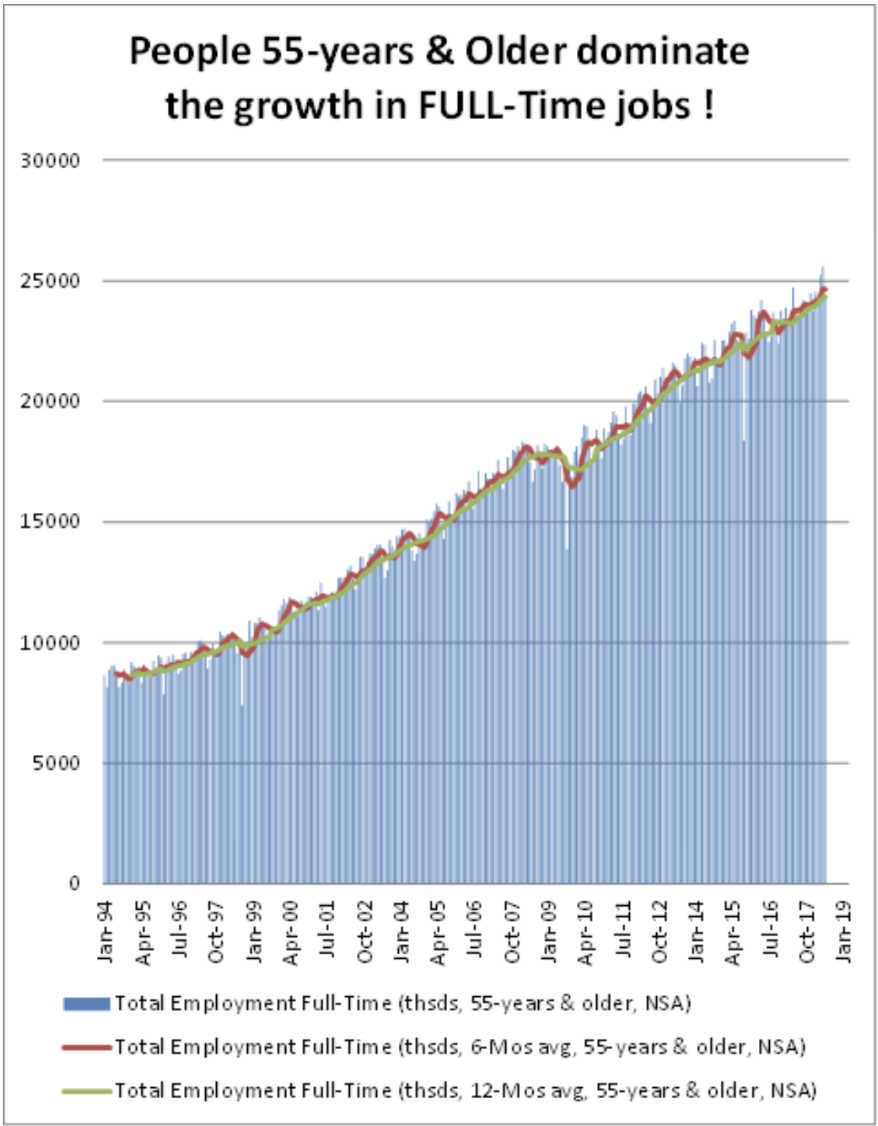

Hermann argues that a major impediment to wage growth is older people staying in the workforce longer. Older workers are less likely to leave a job for a higher paying one and less likely to demand big salary increases. That’s a trend he sees coming to an end, but not until 2022 when the Baby Boom generation starts making its way out of the workforce at a much faster rate than they are now.

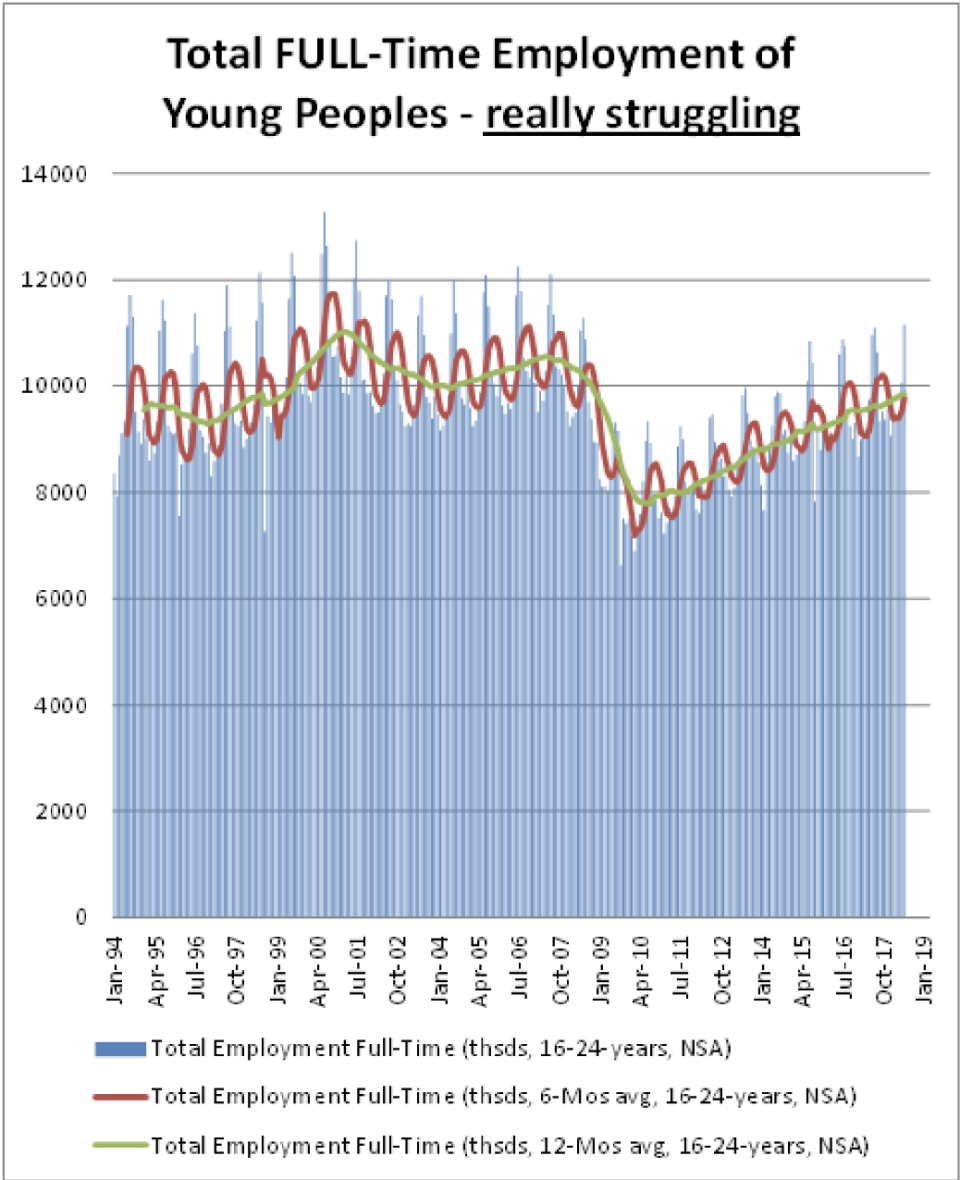

“It’s a lousy thing to say but in part by holding onto an increasing percentage of jobs over last eight years older workers have served as sort of a bottle neck for younger age cohorts to climb the ladder,” Herrmann told Yahoo Finance. “They’ve sort of suppressed some of those job opportunities.”

While previous generations were retiring in their later years, Boomers have been slow to leave the workforce for a number of reasons, beyond the fact that people are living longer.

“The main issues are insufficient savings for retirement, the need to work to make ends meet, supporting kids through college and beyond and in some cases helping to support older family members, like parents,” Herrmann said.

To simply return prime age employment — jobs for people ages 24-49 — to where it was before 2007 the U.S. will need two more years of solid gross domestic product growth, Hermann says. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows these workers have still not returned to their pre-crisis working numbers.

During the recovery from the financial crisis older workers have witnessed a full recovery in wages, unlike their younger counterparts. But if the country can generate growth of 2% to 2.5% a year, as Herrmann expects it will, that should change.

As older workers retire, younger workers will move up to higher positions, increasing the quit rate and driving wages higher.

However, if the United States has a recession before 2022, which a number of experts are predicting — because of the length of the current economic expansion, the build-up of leveraged debt in private and public markets and the increasing uncertainty of President Donald Trump’s tariffs and trade war rhetoric — it could be a catastrophe for the old and the young.

“If you get the recession sooner it’s definitely a problem for the Baby Boomers, for sure,” Herrmann said. “But the fact that the government deficits would rise and rise sooner and then could be high for a protracted period of time, all through next decade, then that would increase the tax burden on young people. That’s a double negative in this situation.”

—

See also:

Wall Street managers have cost Americans more than $600 billion over the past decade

It’s the end of the world as we know it, and investors feel bullish

Global debt jumped by $8 trillion in Q1, rising to record $247 trillion

Dion Rabouin is a markets reporter for Yahoo Finance. Follow him on Twitter: @DionRabouin.

Follow Yahoo Finance on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn.