As Atlanta’s White Population Grows, School Board Election Focuses on Equity

During last year’s racial protests in Atlanta, rapper Clifford “T.I.” Harris tried to bring some calm to the violent clashes with police by referring to his hometown as Wakanda, the technologically advanced homeland of comic book hero Black Panther.

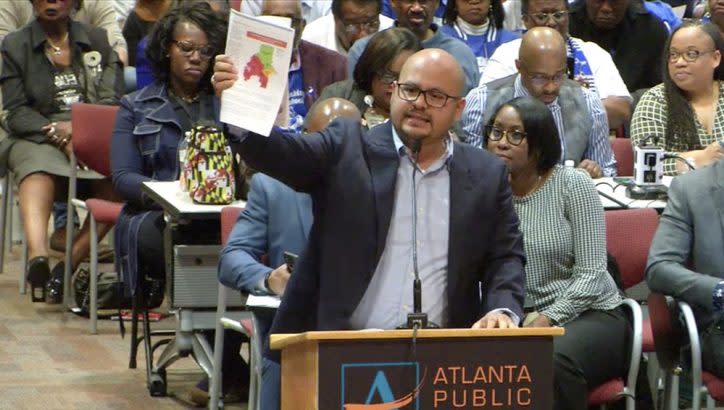

But Ricardo Miguel Martinez, president of the Latino Association for Parents of Public Schools, an advocacy group drawing attention to persistent achievement gaps, wasn’t buying it. “We’ve got to stop saying Atlanta is Wakanda,” he told The 74. “In Wakanda, Black and brown kids know how to read.”

Sign up here for The 74’s daily newsletter. Donate here to support The 74's independent journalism.

Martinez is among those looking to next Tuesday’s school board election in Atlanta — where all nine seats are up for grabs — as an opportunity to address long-standing inequities in the 51,000-student, majority Black district. Pre-pandemic test scores showed that only about a third of Hispanic and a quarter of Black students scored proficient or higher in math and English language arts, compared with over 80 percent of white students.

“This election is where we start to say no more,” Martinez said.

In a district experiencing seismic demographic shifts, candidates represent a wide cross section of residents, from some who prioritize the most marginalized students to those who are well-connected to the city’s power structure. Atlanta is an emerging tech hub, where projects like Microsoft’s westside campus are driving up local real estate costs. Lower-income families are increasingly fleeing the city for more affordable housing in the suburbs, leaving some advocates to wonder if their voices are being heard.

“It really feels like our families are being forced out,” said Kimberly Dukes, the executive director of Atlanta Thrive, which helps parents track the quality of their children’s schools. “A lot of people look to Altanta as a dream. If you have money, you may be all right.”

This is the last time all seats will be on the ballot at once. A new state law, passed last year, will stagger the terms of board members. That means five of the winners will run again in two years, and four will serve a full four years.

Four incumbents, including board Chairman Jason Esteves, are running for re-election, along with 18 challengers. Only one incumbent, Michelle Olympiadis, is running unopposed. The board manages a $1.4 billion budget, roughly twice that of the Atlanta City Council. But in a year when voters are also choosing the mayor and council members — and when crime rates and a lack of affordable housing have dominated the news — Esteves wonders if education is getting the attention it deserves.

“We’re at a pivot point as a school system and as a city. We have the opportunity to tackle generational issues,” he said. “The issues we have with poverty are manifested in the things we’re seeing related to crime. How we tackle those issues directly impacts the school system.”

A September FBI report showed a staggering 62 percent increase in homicides between 2019 and 2020. The fatal stabbing in July of a woman and her dog in the city’s Piedmont Park is among the senseless crimes leaving the city on edge and calling for solutions.

Crime has also become a central issue in the mayor’s race, with some candidates drawing connections between the role of education and improving the quality of life for residents. With Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms not running for re-election, the slate includes former mayor Kasim Reed, who has promoted increased use of recreation centers to deter youth crime. Meanwhile, Courtney English, a former school board chairman, is running for city council president. He’s currently director of community development for a nonprofit providing afterschool programs in apartment complexes near low-performing schools.

City leaders don’t have any authority over the district, but a platform that includes coordination between the board, the council and the mayor’s office can “carry a lot of weight,” said Greg Clay, who served on a task force that wrote the district’s equity and social justice policy in 2019. He added that council and mayoral candidates who say, “That’s not my responsibility” when asked about education won’t be well-received.

‘A change in the demographics’

With more white and affluent residents drawn to Atlanta’s tech and financial sectors, the city is considered to have the widest wealth gap in the nation.

Those population shifts are fueling a threatened secession by the high-priced Buckhead neighborhood, where rising crime — including a 40 percent increase in homicides this year — is the top concern. A separate Buckhead City would be a financial blow to the district’s tax base. One analysis estimated the district would lose $232 million — about a quarter of its local tax revenue. The legislature would still have to pass a bill to bring the question before voters in November 2022.

“The status of nearly 5,500 APS students who live within the boundaries of the proposed city would be in limbo,” according to a statement from the district.

For now, parents in Buckhead and other north Atlanta neighborhoods have more immediate concerns — traffic gridlock, underfunding of International Baccalaureate and dual language immersion programs, and a splitting of some elementary schools that has put an added strain on parents. They say they fight the perception that they’re spoiled and always get their way. “There is commentary at times about how North Atlanta gets everything at the cost or sake of other clusters,” board candidate Jennifer McDonald said at a September candidate forum. “Frankly, I don’t feel like that’s accurate or fair.”

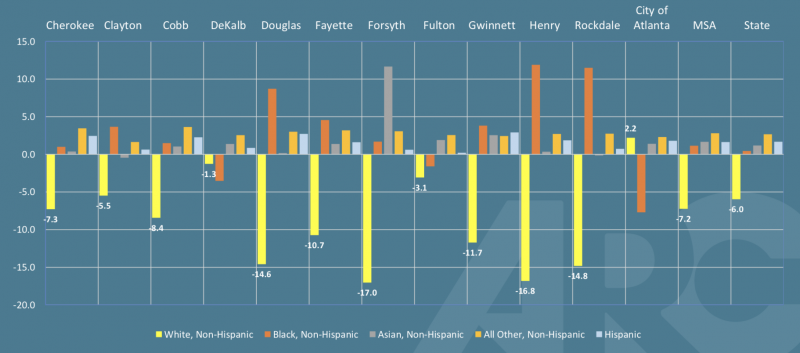

Black families, meanwhile, are increasingly moving to the suburbs, where housing is more affordable. Between 2010 and 2020, the growth of the white population in Atlanta was almost five times that of Black residents, according to data compiled by the Atlanta Regional Commission.

“We’re going to have a lot of voters who know very little about what is going on in the schools,” said Esteves, adding that those who put their children in schools in the city’s wealthier neighborhoods, north of downtown, might not understand why a school on the south side receives more funding per student. “We have been … focused on equity and distributing resources based on need. A change in the demographics of the city requires us to continually talk about how Atlanta Public Schools does things and why.”

But Martinez said higher per-student funding hasn’t changed the culture of low-income schools. His organization’s equity report argues that the district needs to do a better job learning what makes a team of teachers successful at one school and replicate those practices at schools that haven’t seen academic growth in years.

The fate of stagnating schools is another issue facing the new board. Earlier this month, members approved a plan that directs Superintendent Lisa Herring to implement a “high-impact intervention” if a school doesn’t improve after three years. Those actions can range from merging under-enrolled schools to allowing charter school organizations to run them. Olympiadis was the only one on the board to oppose the policy, arguing that charter schools drain resources from the district.

According to a 2021 budget document, 17 percent of district funds go toward charters, a share that’s still growing as charter schools add more grade levels. “All that money goes out the door before we figure out how we’re going to disperse funds across the rest of our schools,” Olympiadis said in an interview.

While school choice hasn’t been a major point of debate in the campaign, Equity in Education, a nonprofit that trained 23 potential candidates for this year’s election, has endorsed those who support “expanding school options,” said founding executive director Anthony Wilson. The organization’s platform is for students to have a “high-quality school within walking distance of their home,” he said.

Whether Herring can ensure more families have access to those high-quality schools is one issue the newly elected board will consider when it decides whether to renew her contract in 2023. Several candidates have acknowledged that she could not have stepped into the role at a worse time, and has done her best considering the challenges of the pandemic and remote learning. As with urban districts nationally, educators and parents worry the pandemic has only worsened achievement gaps. Districtwide, the percentage of elementary school students scoring in the lowest level in reading increased from 34 percent in 2019 to 46 percent this year.

In fact, yawning achievement gaps played an important role in the decision to hire Herring in the first place. Under former superintendent Meria Carstarphen — who helped the district move past a 2013 cheating scandal — there was overall growth in the percentage of students scoring proficient on state tests. The graduation rate has reached 80 percent, up from 51 percent in 2012.

But board members who voted to replace Carstarphen, and advocates for Black and Hispanic students, said those gains haven’t been spread evenly across the district. Seventy-seven percent of Black students graduate, compared to almost 97 percent of white students.

‘Struggling in the system’

Other candidates have reservations about Herring, saying she needs to seek more parent and community input before making decisions. During the September forum, some candidates noted that the district often blindsides parents by sending important messages on Friday afternoons. A plan to change high school schedules to accommodate longer school days for elementary students drew widespread opposition.

The district has since hired a marketing and communications firm to improve its relationships with parents, incumbent Erika Mitchell said during the forum.

Royce Carter Mann, a 19-year-old candidate who graduated from the district last year, is among those calling for greater transparency. Though young, Mann grew up in a politically active family with a grandmother who worked in the Carter administration. Named for the former president, Mann campaigned for Sens. John Ossoff and Raphael Warnock in a January special election that gave Democrats control of the U.S. Senate.

Mann nurtured his interest in education policy while interning for the Atlanta school board. He pushed for the district’s new Center for Equity and Social Justice and wants students to have more say in their education.

“When students are included, it’s almost as a reward for being a high-achieving student,” he said. “It’s the students who are struggling in the system that we need to listen to the most.”

Mann supported a campaign to rename his school Midtown High last year, dropping the name of Henry W. Grady, a Civil War-era journalist who didn’t support equality for freed slaves. Last week, another school was renamed for Atlanta baseball legend Hank Aaron, replacing that of Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader Forrest Hill.

While the symbolism is important, parents in the city’s predominantly Black southside neighborhoods want more than just school name changes. At the September candidate forum, board member Mitchell, whose constituents include those families, said, “We need to have equitable options in our schools so we can retain our students in our area, so they can be proud of the schools they’re attending.”

Lead Image: Atlanta Public Schools board members and officials celebrate the opening of the district’s new Center for Equity and Social Justice. (Atlanta Public Schools)