Big Pharma’s great lab monkey shortage: A crackdown on smuggling is causing chaos in America’s vital drug development pipeline

When Masphal Kry was taken into a back room for questioning at New York’s J.F.K. International Airport one morning in November 2022, it wasn’t immediately apparent to him that he was going to miss his connecting flight.

The director of wildlife and biodiversity for Cambodia’s Ministry of Agriculture, Forest, and Fisheries (MAFF), Kry was en route to an international wildlife conference in Panama when agents of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service ushered him into the interview room. They informed the 46-year-old bureaucrat that the United States had a warrant for his arrest, charging him with smuggling wild primates. Kry assured them they had made a mistake, according to a transcript of the encounter later released in court proceedings.

“I’m from a conservationist background,” he told them. He encouraged them to check his bag (perhaps to show it contained no monkeys) and to talk with his friend, a more capable English speaker, who was headed to the same conference and out in the airport with Kry’s luggage.

The transcript suggests that Kry was confused, a man whose day had taken an unexpected turn but who was mostly worried about making his plane. He could not have guessed then, of course, that more than a year later he’d still be in the U.S.—on house arrest, awaiting trial on charges that carry a maximum sentence of 145 years in prison.

Nor could he have imagined that his arrest would entangle him in an epic, messy, international drama that’s still dragging on. It set off a chain of events that has left more than 1,200 monkeys in caged limbo in U.S. corporate labs, shaken a lucrative trade sector for his country, and kneecapped America’s multibillion-dollar pharmaceutical testing industry—critical for the development and approval of drugs and medical treatments.

Operation Longtail Liberation

For the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, apprehending the Cambodian official was a victory in a yearslong investigation. “Operation Longtail Liberation” had uncovered deep and alarming flaws in the supply chain of captive-bred lab monkeys used in America’s biomedical research and pharmaceutical industries. Implicated in the scheme was one of the trade’s supposed regulators: Kry’s employer, the agency charged with protecting wildlife in Cambodia, which was and remains responsible for issuing permits to ensure the legal trade of animals. (Cambodian government offices in the U.S. and Phnom Penh did not respond to requests for comment. In a statement at the time, MAFF said it was “surprised and saddened” by Kry’s arrest and that it upheld the laws and principles of international wildlife trade.)

The eight-count, 27-page indictment, unsealed after the arrest, alleges a sprawling criminal scheme enabled by officials at the top of Cambodia’s bureaucracy. Kry, along with the Forest Administration’s top boss and six employees of a Hong Kong–based company with monkey breeding farms in Cambodia, is accused of conspiring to sell hundreds of wild-caught monkeys, packaged with falsified permits, into the highly regulated pipeline of captive-bred animals for laboratory testing. Two unnamed American companies are also mentioned as “unindicted co-conspirators.”

There is even grainy cell phone video that purports to catch Kry in the act. In the video, submitted as evidence in the court case and viewed by Fortune, Kry, dressed in a blue gingham shirt and sunglasses, watches as workers unload caged monkeys from the back of a pickup truck at the Cambodian breeding facility.

In the scheme, the U.S. government alleges, wild monkeys were given identification tags transferred from sickly captive-bred animals that would later be euthanized. And, it alleges, the wild-caught macaques were exported to the U.S. with Cambodian government-issued permits that falsely identified them as captive-bred.

“The practice of illegally taking [macaques] from their habitat to end up in a lab is something we need to stop,” declared Juan Antonio Gonzalez, then–U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, after Kry’s arrest. “Greed should never come before responsible conservation.”

The monkeys aren’t the only victims, said Edward Grace, assistant director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in a press release. Wild-caught monkeys passed off as captive-bred can present disease risks, and can skew scientific research: “The health and well-being of the American public [is] put at risk when these animals are removed from their natural habitats and sold illegally in the U.S. and elsewhere.”

Few would disagree with that rationale. But in America’s $586 billion biopharmaceutical industry, Kry’s arrest created a crisis: It effectively halted the import of Cambodian long-tailed macaques, which had made up some 60% of the industry’s lab monkey supply. Known in the field by the more clinical, distancing term “nonhuman primates,” or NHPs, these animals were used in the quick development of vaccines for Ebola and COVID, and in research involving everything from fertility disorders to gene therapies.

The sudden severing of the industry’s main monkey supply chain was a jolting debacle for drug development companies that rely heavily on monkeys to test the safety of new medicines. (Pharmaceutical companies generally don’t do this work themselves, but outsource it to contract research organizations.)

For much of the past year since Kry's arrest, the homepage of the National Association for Biomedical Research has screamed, “ADDRESS THE NHP CRISIS TODAY!” and warned that the throttling of the Cambodian NHP supply chain “has put the development of new drugs to treat thousands of diseases for which there is no treatment or cure at significant risk.” Some in the industry even argue that the U.S. is ceding its scientific edge—and national security, especially in another pandemic—to China, which has both a robust monkey-breeding infrastructure and world-dominating biotech ambitions.

And industry insiders whisper that the crackdown isn’t so much about conservation or the purity of the lab testing supply chain as it is about catering to the interests of their longtime adversary: animal rights activists, who want to put a stop to all primate testing. (Read more about why Big Pharma can't seem to quit animal research here.)

In any case, the controversy has thrown a spotlight on an aspect of biomedical work that many prefer to keep in the shadows—the uncomfortable and unpopular reality that medical progress, at least for now, depends on sacrificing some of our closest mammalian relatives. (If lab animals don’t perish in pharmaceutical testing, they are generally euthanized.) And it adds new urgency to an age-old question: Do benefits to humans justify undeniable harm to so many other living, breathing, sentient creatures?

Industry insiders and critics agree, the best long-term solution is to not use animals in research at all. But the technology is not there yet. For now, America still needs its lab monkeys.

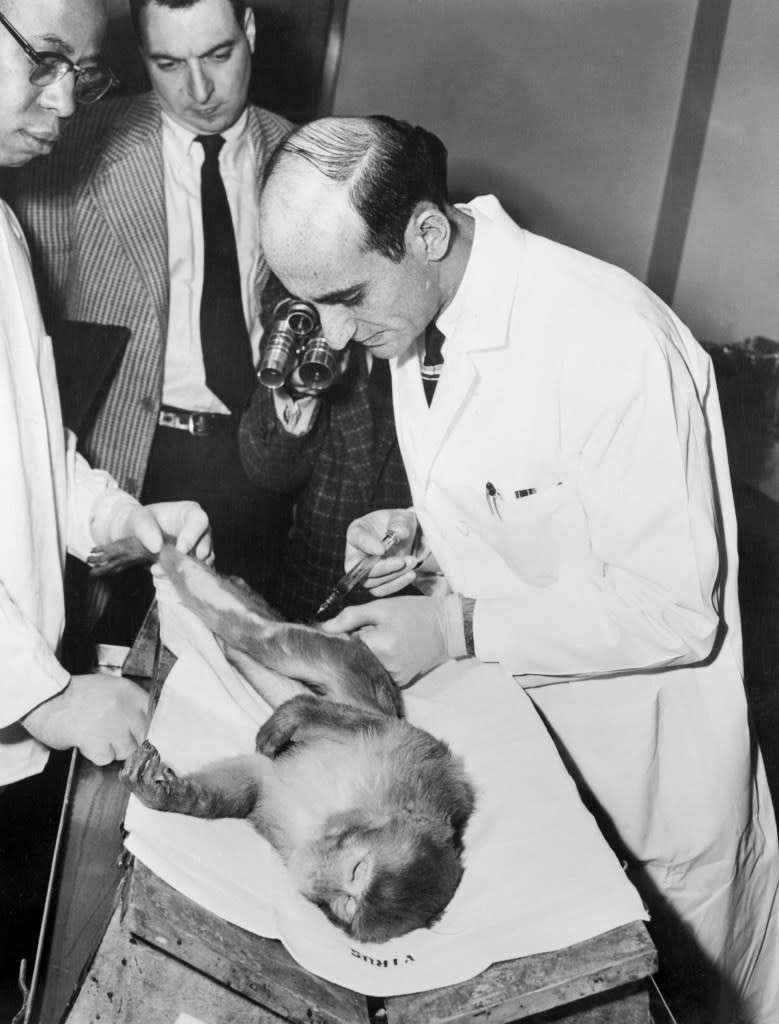

Man’s reliance on monkeys for medical insight goes back centuries: Galen, famed physician of ancient Rome, used macaques for his influential anatomical studies in the second century AD. Today, monkeys make up just 0.5% of all animals used in scientific research, but they are in high demand for some of the most urgent areas of science: Their close relation to humans makes them key to infectious disease and brain research, and they are often considered the only relevant animal model for testing the fast-growing class of drugs known as biologics. At least 20% of drugs use NHPs in their required safety testing.

Fortune talked to dozens of primatologists, research scientists, conservationists, animal rights advocates, and biotech industry representatives. Each sees the issues at the core of this still-unfolding story as incredibly high-stakes—a matter of life and death, really—but for vastly different reasons, and for different beings.

They disagree over nearly every aspect: Is Kry a craven wildlife trafficker, or simply a government official who carried out orders on the job, in the interest of public health? Is the biomedical supply chain riddled with monkey-smuggling, or are crimes like those described in the indictment rare, isolated incidents? Are long-tailed macaques endangered, or a “hyper-abundant” nuisance? Does the industry desperately need monkeys to create lifesaving drugs—or could we be doing better, more humane science without them?

Most urgently: What’s to be done now? More than a year after that fateful day at J.F.K. airport, Kry’s case moves slowly through the federal court system of Florida’s Southern District. A key supply chain that feeds America’s pharmaceutical research apparatus remains snarled. And the future of a primate species mankind has relied upon for medical advancement hangs in the balance.

For the biopharmaceutical industry, a chaotic aftermath

Kry’s arrest and its knock-on effects arrived at the worst possible moment for the biomedical research community, which was already years into a cascading, geopolitically fraught monkey supply crisis. The Kry incident was just the latest domino to fall.

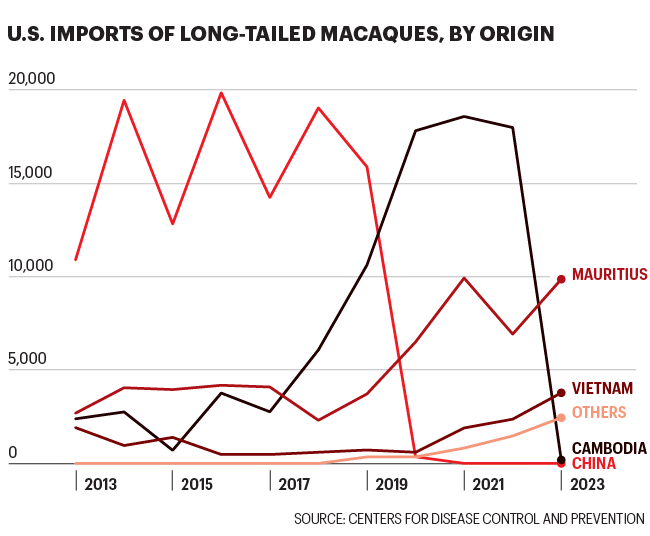

When China, previously the largest source of lab monkeys for the U.S., cut off exports of the animals at the beginning of the COVID pandemic, the looming shortage that had long been an anxiety for scientists and researchers became acute. U.S. importers pivoted almost overnight to breeding farms in Cambodia to fill the massive shortfall. Between 2020 and 2022, Cambodia provided the U.S. with about 18,000 of the roughly 30,000 nonhuman primates that were imported each year. Still, as the COVID vaccine race ramped up, there simply weren’t enough monkeys. In that period, prices increased tenfold, soaring from around $2,000 per animal to more than $20,000. Unborn Asian monkeys were even being purchased as “futures” in the frenzy, one U.S. government official said.

The high-profile arrest and its aftermath threw another major wrench into the works—and as Cambodian macaques disappeared from the market, the price of monkeys rocketed up even higher, to $55,000 per animal or more in some cases.

The problem now, gripes the industry, is the federal government. Its effective ban on Cambodian long-tailed macaques is clear to see by the numbers: In 2022, 17,992 Cambodian long-tailed macaques traveled to the U.S., and in 2023, just 189 made that journey. (Imports from Vietnam and Mauritius have increased in that period.)

Since late 2022, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has refused to clear shipments from Cambodia without incontrovertible evidence that the animals were genuinely bred in captivity. That’s a hurdle the industry still hasn’t managed to clear. It’s working on potential solutions including genetic testing to prove monkeys were bred in captivity, but more than a year later, industry representatives grumble that the agency has never explained the abruptly implemented policy or what’s required of them.

Fish and Wildlife disputes this characterization. In an email to Fortune, a spokesperson said that “the Service hasn’t implemented any new policies,” but is simply upholding its obligations to ensure wild-caught macaques are not illegally imported or exported. To the U.S. regulators, the role of Cambodia’s wildlife permitting authority in the alleged conspiracy raised questions about the legality of all monkey trade from the country. Meanwhile, a spokesperson with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration suggests that the industry’s concerns about the NHP shortage are, at least for now, overblown, telling Fortune, “We are not aware of a slowing of innovation.”

Caught up in the confusion are those 1,200 Cambodian monkeys, which Charles River Laboratories, one of America’s largest contract research organizations, imported between late 2022 and early 2023. Those animals, an “inventory” worth $20 million by the company’s estimate, now inhabit an odd and indefinite limbo—residing at the company’s labs but off-limits for scientific use.

Some say this government crackdown is overdue, and that the biomedical research industry has willfully ignored smuggling in the monkey supply chain for years—an explosive allegation. The Cambodian NHP pipeline runs to the labs that serve America’s largest pharmaceutical companies and most renowned institutes (some of them, like the National Institutes of Health, belonging to the U.S. government itself). None of these entities were eager to contemplate the possibility that monkeys they used to develop American medicines were nabbed from the woods or streets by traffickers in Southeast Asia.

Meanwhile another storm cloud hovers for the industry: the possibility that the long-tailed macaque, the monkey most used by far in private industry, will be declared entirely off-limits. In 2022, the respected International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classified the species as endangered, naming demand for research animals as one of its primary threats. The designation doesn’t immediately impact the monkey’s trade, but it leaves the industry fighting another awkward accusation: that it’s driving the long-tailed macaque to the brink of extinction. It’s a narrative that the industry outright rejects, arguing that the creature is plentiful, running rampant in Southeast Asia.

Meet the macaque

At the very center of this global, high-stakes tug-of-war is the long-tailed macaque (pronounced ma-CACK), a scrappy everyman of the monkey kingdom that ranges across Southeast Asia and is the world’s most traded primate.

In the U.S., 95% of monkeys imported for lab work are long-tailed macaques, the species Kry was accused of smuggling. A monkey of many names—Macaca fascicularis, the crab-eating macaque, and the cynomolgus monkey (cyno, for short)—the brownish-gray primate is about the size of a very large house cat, possessing neither the physical majesty nor the spectacular colors of the great apes.

As its name indicates, the long-tailed macaque does have an impressively long tail, which it uses to balance as it leaps great distances, as well as sharp teeth, close-set eyes, and a tuft of Trumpian hair that can spike into a fluffy gray mohawk. It can be seen swimming and scurrying, and is so adept at using tools—to, say, forage for food or floss its teeth—that its own intelligence is a hot topic of academic study.

Above all, the long-tailed macaque is adaptable, a trait that has served it well as deforestation and development have transformed Southeast Asia. “Macaques seem to do really well in complicated, edgy, messed-up habitats,” says Agustín Fuentes, a Princeton professor and primatologist who has studied the species for decades. They actually prefer living near people—"interacting, competing, getting along”—to the deep cover of jungle, he adds.

These days, the animals often amass at temples and other tourist sites, where they’re well fed and engage in spectacles—showing off their dexterity by “taking selfies” with tourists, for example. They tend to thrive in human proximity, growing fat, reproducing prodigiously, and creating a sense they’ve taken over. They’re known to raid crops, break into homes and stores, and snatch things like cell phones to cleverly ransom back for food.

You can’t blame monkeys for being monkeys (especially when they’ve been displaced by people), but managing the human-macaque interface is a real issue for governments in Southeast Asia. Facing public outcry, some resort to sterilization or even mass culling.

Opportunistic trappers are also out to get the long-tailed macaque, for sale into the TikTok-fueled pet monkey market or other channels of their illegal trade. According to the indictment, Kry and his superior also found a way to profit from the country’s wild monkeys—funneling them into the biomedical supply chain.

The long-tailed macaque only became industry’s favored lab monkey in recent decades. It was the rhesus macaque that played a starring role in the polio vaccine race: Between the 1930s and the 1950s, America sometimes imported more than 100,000 per year from India—monkeys that were taken from the wild, as was common practice then. That brisk trade ended in 1978, when India, already concerned about depleting stocks, banned exports after learning the U.S. used some of the monkeys in military experiments during the Cold War arms race.

Readily available across Southeast Asia, the long-tailed macaque emerged as a winning alternative. The species had the virtue of being slightly nicer (less likely to bite handlers) and smaller (saving money on drugs in preclinical studies) than the rhesus macaque.

A ripple effect

As it turns out, the monkey-breeding operation that Kry is accused of conspiring with in Cambodia, part of the Hong Kong–based company Vanny Bio-Research, is no bit player in the industry. (Vanny did not respond to requests for comment, but in a statement at the time of Kry’s arrest, the company denied any wrongdoing.)

Up until then, Vanny had been the principal monkey supplier to one of America’s top importers of nonhuman primates, the Indiana-based contract research organization Inotiv. In 2022, Cambodian monkeys accounted for a quarter of the company's revenues, roughly $140 million. Fish and Wildlife’s investigation into Inotiv’s NHP sourcing began years ago, with two of its subsidiaries receiving grand jury subpoenas in 2019 and 2021. In May 2023, Inotiv was notified that the SEC was investigating its monkey imports. (Inotiv also made headlines in early 2022 when the government seized 4,000 beagles, 446 in acute distress, from its Virginia dog-breeding facility.) Inotiv did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

At Inotiv’s Boston-area competitor, Charles River Laboratories—which uses more nonhuman primates than any other American company and had sourced 60% of them from Cambodia—executives quickly heard of Kry’s November 2022 arrest, which set the industry aflutter. But they weren’t worried about their own monkeys, says Birgit Girshick, the company’s chief operating officer. Vanny was not among Charles River’s direct suppliers, and its own Cambodian breeder had been a trusted partner for some years (and has not been indicted).

But by February, Charles River had become ensnared in the government’s investigation too. That month, it received a grand jury subpoena from the Department of Justice related to shipments from its Cambodian supplier. Since then, the company has disclosed that it’s the subject of parallel federal criminal and civil investigations, as well as an SEC probe, related to its nonhuman primate sourcing from Asia. The company stresses that it’s cooperating with the investigations and believes it has done nothing wrong.

Speaking on an earnings call several days after the company received its subpoena in February 2023, Charles River CEO James Foster framed the government’s effective block on Cambodian monkey imports as an industry-hobbling headache. “We have to get through this logjam,” he told investors. “This is not an acceptable situation for patients or for drug development.”

It was also potentially very bad for business: In recent years, the lucrative work of conducting preclinical safety tests for pharmaceutical companies had delivered blockbuster growth for Charles River, in part because of the soaring price of monkeys and the panic over their scarcity. In 2021 and 2022, drug companies were booking animal-testing services two years in advance, simply to reserve a spot in line. The Cambodian NHP impasse with the U.S. government could shave up to $160 million off Charles River’s revenues in 2023, Foster warned.

Indeed, the freeze on Cambodian monkeys had the whole industry spooked. NHPs are a particularly tricky supply chain to rebuild because monkeys aren’t widgets. Captive-bred monkeys take years to breed, and the global competition for those animals is stiff. Rumors swirled: Would the government go after Vietnam’s breeders next?

What made the situation “frustrating,” Foster said, was that this urgent supply crunch had an obvious solution. “It’s not like there literally aren’t enough animals in the world to satisfy demand,” Foster told analysts. “The animals are available.”

Adding insult to injury, Charles River already had enough monkeys in its labs to fill a large elementary school—those 1,200 from Cambodia that it had already purchased, imported, and transported to its facilities. It just wasn’t allowed to use them.

An important, often invisible, cog in the drug industry

Charles River Laboratories began humbly 77 years ago when a bow-tie-sporting veterinarian named Henry Foster purchased 1,000 rat cages from a Virginia farm and set up a one-man lab in Boston. Before long, he was breeding rodents for other researchers in the region. (Their progeny later included the Astromice, the first earth animals exposed to moondust.)

Over time, Charles River became an increasingly sophisticated, full-service partner to life sciences companies and researchers. Today, under the leadership of Henry’s son James, the company doesn’t just provide the animals; it designs and runs studies, identifying drug targets and evaluating the safety and efficacy of new medications. Its clients include big pharmaceutical companies and the National Institutes of Health, as well as small biotechs, academic researchers, and even the occasional parent trying to develop a cure for a child’s rare disease.

In the wider business landscape, Charles River doesn’t particularly stand out: Its $4 billion in annual revenue makes it just America’s 745th largest company. But the contract research organization based in Wilmington, Mass., with 21,000 workers has quietly become an outsize player in America’s pharmaceutical and biotech industries: It works with every major drug company and on more than 80% of the medications that come out of them.

Put simply, Girshick says, “They couldn’t get drugs to market without us.”

When I first spoke to Girshick last April, Charles River had enough monkeys in the U.S. to do its scheduled studies, but Girshick said they were down to a couple of months’ supply. “The time is really ticking,” she told me.

Meanwhile Matthew Bailey, longtime president of the Foundation for Biomedical Research as well as the National Association for Biomedical Research (NABR), industry groups that represent academic institutions and multinational companies like Charles River, wasn’t just frustrated with the federal crackdown on Cambodian NHP imports: He was also suspicious.

To the career lobbyist, hardened by years of battles with the industry’s most persistent nemesis, the whole federal case smacked of animal activism—from the code name, Operation Longtail Liberation, to the deployment of undercover video, a common tactic of People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and similar groups. A Fish and Wildlife spokesperson said "the Service's Office of Law Enforcement rejects the idea that its decisions are driven by activist pressure; its actions are driven by its conservation mission and its obligations to enforce the law.” (A former investigator noted agents often engage in creative wordplay when selecting code names—as with “Operation Ornery Birds.”)

The activist battle

On a warm Friday morning in April 2023, a handful of protesters from PETA stood in a line outside a Miami federal courthouse. A few hoisted signs—“No gag order on monkey-smuggling evidence!”—while others held macaque masks over their faces.

Lisa Jones-Engel, a senior scientific advisor with the organization’s laboratory investigations department, previewed the day’s expected proceedings in front of a camera for a PETA broadcast, while a middle-aged man in a suit who didn’t identify himself filmed the scene—a menacing gesture, Jones-Engel thought—on his cell phone.

Once a globe-trotting field primatologist, Jones-Engel is now four years into a battle to dismantle the industry she once worked for, on a mission to end the use of primates in biomedical research, full stop.

She celebrates Operation Longtail Liberation as a blow to a despicable and corrupt trade, and had come all the way to Florida from her home in Utqiagvik, Alaska, to watch the case against Kry unfold. She gasped when the video of Kry at Vanny’s farm played in the courtroom—disturbed, she told me later, by the distinct vocalizations of young long-tailed macaques in distress.

The suffering and death of animals for the sake of science has always been an ethically fraught and divisive issue. Animal rights organizations and the scientific community have been duking it out for years. Vocal activists tend to dominate the public debate, arguing that animal research, which they consider a form of intolerable cruelty, is unnecessary (couldn’t technology do that?) and misleading (can we really understand a human disease by studying a monkey?).

Scientists and industry representatives reflexively rebut both those points—and complain mightily about the misinformation that some animal advocates spread. But many prefer not to engage for fear of being targeted by a group like PETA, a 9-million-member-strong organization whose tactics have included protesting at researchers’ homes and infiltrating labs. (The general public is split on the matter, with 52% of Americans opposing animal research in a 2018 survey by the Pew Research Center.)

It’s worth noting that the question of whether animal testing is right or should continue is not what’s at issue in the case against Kry and his codefendants, or the restrictions on Cambodian monkey imports. The animal advocates outside the courtroom in Miami were there to cheer on the government’s case, but Fish and Wildlife’s Operation Longtail Liberation is not, on its face, aligned with their efforts to end all animal testing on moral grounds.

Conservation—the protection of wildlife and upholding of the rules governing its international trade—is the focus of the federal case. (Read more about the thorny question of whether the long-tailed macaque is endangered here.)

The industry of captive breeding farms that took root in Southeast Asia was supposed to reduce pressure on the wild population of long-tailed macaques. Still, the 2022 IUCN assessment asserted that demand from the biomedical trade is one of the threats endangering the species. If U.S. or international wildlife regulators adopt a similar stance, the industry faces a far more serious supply disruption: A ban or severe restriction of the species’ trade could end its use in research for good.

PETA’s Jones-Engel, who has petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to do just that, talks openly about this being her end game. And if the effort is successful, Bailey, the industry lobbyist, says that would be a disaster: “I think the net effect is that preclinical research for this species in the United States is over.”

Industry insiders and critics agree, the best long-term solution is to not use animals in research at all. The FDA opened the door for pharmaceutical companies to use nonanimal alternatives in safety testing several years ago. And promising tech, including AI and organs-on-a-chip—miniature systems that mimic the properties of human tissues and organs—are advancing quickly and helping reduce the number of animals used in studies. But those technologies are not yet robust or established enough to adequately assess the risk of drugs to humans in most cases, the FDA told Fortune.

In other words, America still needs lab monkeys.

The tip of the iceberg?

The biomedical community professed shock at the allegation that a wide-ranging wild-caught macaque smuggling scheme existed in its supply chain. Industry representatives said they believe smuggling is largely prevented by in-country regulation and company audits.

Girshick of Charles River Laboratories told me that she remembers being “dumbfounded” when she first heard about Kry and Vanny’s alleged crimes: That a breeder would take the risk of infecting the captive-bred population with diseases from wild monkeys just didn’t make sense, Girshick said, purely from a self-interested business point of view.

But conservationists, primatologists, and others who have tracked the issue in Southeast Asia say the Kry case is the tip of the iceberg, and that for years wild long-tailed macaques have been smuggled into the region’s breeding farms to prop up the industry’s inadequate supply chain.

Dave Windley, a financial analyst who covers Charles River and Inotiv for Jefferies, has struggled to square the industry’s claims that it has sufficient safeguards to prevent these kinds of shenanigans with his own research. “We’ve dug out a bunch of news stories and white papers and things like that, that just talk about how prevalent smuggling is, and honestly how it’s been going on for a long, long time,” he says. (This reporter found a similarly robust and persuasive historical record.)

As for the Cambodian breeding facility, Vanny Bio-Research, that Kry is accused of delivering monkeys to, it should have been obvious that there was a problem, says Tim Santel, a retired Fish and Wildlife Service special agent who oversaw Operation Longtail Liberation until his retirement in 2020. “The light bulb was like, there’s actually zero way that the tens of thousands that are being brought in, [from] a facility that only has X amount of animals—it can’t be,” he says. “Those numbers don’t jibe.”

A lucrative business that's hard to scale up

Indeed, there’s an inescapable math that makes breeding NHPs a several-years-long, complicated process. Female long-tailed macaques aren’t sexually mature until the age of 4 or 5. They’ll give birth to a single monkey after a gestation period of 165 days; the baby will be weaned after six to eight months. Biomedical research and pharmaceutical testing require monkeys of varying ages, but most need to be at least three years old.

The European Union requires that monkeys used for research must be at least two generations removed from their wild forebears, and while the U.S. has no such requirement, it’s considered desirable here too. Because of all this, there are limits to a monkey farm’s potential productivity.

Even so, Cambodia somehow managed to ramp up its monkey exports very quickly, according to wildlife trade data. Between 2019 and 2020, the year that China stopped its outbound trade, Cambodia more than doubled its worldwide exports of captive-bred long-tailed macaques, from 13,992 to 29,466.

It’s a big business that some say is interwoven with the country’s government. Radio Free Asia has reported on links between powerful politicians and the nation’s monkey farms. In a country where the GDP per capita is $1,800, the economic incentive to catch and sell a macaque for a couple hundred dollars is strong.

On its web page, Vanny Bio-Research’s two Cambodia operations look more tropical resort than monkey farm, with stately white villas and lush topiary trimmed into the word “VANNY.” Media photographs and recent drone footage offer a somewhat different view: a vast expanse of cleared land dotted with rows and rows of uniformly placed monkey sheds.

Founded in 2000, the Hong Kong–based company has campuses in Phnom Penh and in Pursat, a mountainous province with dense forest. Up until the U.S. government indicted six of its employees, Vanny had the industry’s highest seal of approval—an accreditation from the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC International), the industry nonprofit body that audits breeding farms and animal laboratories in 50 countries around the world. AAALAC removed Vanny from its list of accredited organizations in the days following the indictment.

Vanny is accused of paying millions of dollars to several black-market distributors between 2017 and 2022 to purchase thousands of wild long-tailed macaques for the company’s farms, bolstering the numbers it was breeding in captivity.

Among the alleged black-market suppliers was Kry’s employer, Cambodia’s MAFF, which the U.S. government says sourced monkeys from national parks and protected areas. The agency collected $150 to $220 for each animal it delivered to Vanny, charging the higher $220 price for “unofficial” monkeys that it agreed to hide from local officials, according to the indictment. Kry is singled out for dropping off 92 wild monkeys at Vanny on four dates between August 2019 and June 2020 and, on one of those occasions, advising Vanny personnel to create a back road to the farm that would be “more safe for the smuggling.” (The latter incident is captured on a cell phone video surreptitiously recorded by a confidential informant, who was then working at Vanny; Fortune has viewed the video, which is an exhibit in the case.)

In a motion to dismiss the case, Kry’s defense attorneys argue that he was a bureaucrat simply doing his job, carrying out official duties that he was authorized to perform. Documents purporting to support this claim include communications from 2018 that show Cambodia’s MAFF granted Vanny permission to collect 2,000 long-tailed macaques from public places in order to “reduce the risks to people and tourists.” In exchange for “conservation and royalty fees,” the government allowed Vanny “to raise, care, and breed” the animals.

Kry’s defense attorneys argue that Kry had no idea whether Vanny planned to misrepresent those wild monkeys as captive-bred and export them to American labs. And they accuse the U.S. government of improperly launching “a full-on assault” on a foreign ministry. (It’s unclear who’s footing Kry’s legal bills, but he is represented by attorneys from Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld, an American firm that the Cambodian government had hired for lobbying purposes in early 2022.)

What's so hard about breeding monkeys in America?

Kry and his associates stand accused of fudging paperwork certifying wild monkeys as captive-bred, but the implications are broader than that: Animals misidentified as captive-bred can bring unknown disease risks to one another and humans, and unwittingly introduce variables into the controlled scientific process.

Amid those concerns and the broader lab-monkey supply crisis, some in the industry argue the only way to guarantee the U.S. has a reliable, high-integrity supply is to expand domestic breeding.

But breeding monkeys in America “just doesn’t work,” Foster of Charles River Laboratories told an investor audience last March. He knows this from experience: Charles River tried to get into the monkey-breeding business in the 1970s when the company started a colony of rhesus macaques on two uninhabited islands in the Florida Keys. By the mid-1980s, the animals numbered over 1,000, and neighboring communities were complaining that the monkeys had destroyed mangroves, polluted the water with their poop, and even escaped to other islands. A judge finally evicted the colony, but not before Hurricane Georges hit in 1998—killing eight monkeys and loosing 150.

“There’s actually zero way that the tens of thousands [of monkeys] that are being brought in [came from] a facility that only has X amount of animals… Those numbers don’t jibe.”

Tim Santel, a retired Fish and Wildlife agent

Foster recalled the operation as “a nightmare.” Hurricane aside, Foster said, it had been a money pit—cash-flow-negative for 12 years. Meanwhile, he pointed out, the animals are “running wild in Asia and Africa.” All you have to do, he added, is take those feral animals and breed them. Put another way: The business of raising lab monkeys is easier and cheaper to do somewhere other than the United States.

That truth sets up a strange and jarring disconnect that underpins the global nonhuman primate supply chain: The monkeys that end up in America’s gleaming, high-tech labs often started their lives in open-air monkey farms in much poorer countries, where workers wearing only light PPE are paid little to raise and handle animals.

With only basic technology and the practice of keeping the animals in large pens, Girshick concedes that until recently, “recordkeeping was basically nonexistent” at such breeding operations “deep in the woods.”

Caged limbo

Will Cambodian NHPs ever return to America? Foster, Charles River’s CEO, isn’t so sure, and he doesn’t particularly care. For now, his company has averted the NHP doomsday scenario that Girshick had worried about with a crafty workaround: Canada.

As a global company, Charles River has labs outside the U.S. where it can ship Cambodian monkeys. It just had to move the contract work. (PETA has appealed to the Canadian government to block Cambodian monkeys, but the country stands by its process.)

The company still maintains that the government’s claims are without merit, but it is running a tighter ship when it comes to its monkey suppliers: stepping up audits that had fallen by the wayside during the COVID pandemic, and making further investments to help breeding farms upgrade their processes.

Meanwhile, demand for NHPs has eased with 2023’s biotech slump, leading Charles River to use 25% fewer NHPs in 2023—11,400 compared with 15,272 in 2022. Still, Bailey and others in the research community stress that the shortage remains dire.

PETA celebrates the reduction, taking its wins where it can. Last March, after flooding the Fish and Wildlife Service with calls and stationing members outside Charles River’s facilities, it declared victory in stopping the company from sending the 1,200 Cambodian monkeys back to Cambodia—to be “funneled back into the forest-to-laboratory pipeline,” in the organization’s words. (Charles River denies that it ever planned to send the animals back to their origin country.)

But PETA’s proposed solution—to send the stateless monkeys to a sanctuary—hasn’t yet worked out, partly because it’s dauntingly expensive. Angela Grimes, CEO of Born Free USA, which runs a primate sanctuary that holds 250 monkeys in Texas, says it would cost $125 million to buy the land, equipment, and supplies necessary to provide lifetime care for all those monkeys. She wants to help the animals, but says there’s no funding mechanism for such strange circumstances. So the monkeys remain at Charles River—in cages at a lab, but not used as lab monkeys.

Kry remains in a sort of caged limbo as well, awaiting trial in March and living under house arrest in the northern Virginia suburbs. Last summer, the judge granted the former wildlife official a few nightly walks around the neighborhood per week.

He is still the only one of the eight indicted individuals in U.S. custody. Cambodia continues to export monkeys for biomedical research—just not to the U.S. And Vanny is still in business. According to its website, it now offers paternity testing and microchipping to assure clients their monkeys didn’t come from the wild.

Kry remains the silent center of the case. Through his defense team, he declined to comment for this story. At the time of his arrest, his profile on the social media app Telegram offered, as a sort of personal statement, the saying often attributed to Mao: “Everything under heaven is in utter chaos; the situation is excellent.”

This article appears in the February/March 2024 issue of Fortune with the headline, “Big Pharma's monkey business.”

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com