Credit Suisse dives as banking turmoil takes hold in Europe: What's new in the SVB crisis

The collapse of SVB Financial Group’s Silicon Valley Bank on March 10 left global financial markets in their worst state of panic since 2008 on March 13, when cascading bank failures in the United States and Europe caused credit markets to seize, triggering what came to be known as the Great Recession.

Things aren’t that bad this time. But they aren’t good either. Here’s what you need to know:

Here’s what’s happening now

Credit Suisse, Switzerland’s second largest bank, plunged to fresh record lows after its biggest shareholder said it would not raise its 10 per cent stake. Trading in the shares was halted a number of times as volumes soared and the stock plummeted.

Bank stocks in Europe are down in general. The index has lost 13 per cent since last Wednesday, the biggest weekly loss since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last February.

“Markets are wild. We move from the problems of American banks to those of European banks, first of all Credit Suisse,” Carlo Franchini, head of institutional clients at Banca Ifigest in Milan, told Reuters.

The cost of insuring the bonds of Credit Suisse against default in the near-term is approaching a rarely-seen level that typically signals serious investor concerns.

Here is what has happened

U.S. President Joe Biden addressed the nation on March 13, stating he will do “whatever is needed” to protect bank deposits after three mid-sized American banks failed in a matter of days.

The U.S. Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department scrambled the weekend before to erect financial backstops that they said would protect depositors of California-based Silicon Valley Bank and New York-based Signature Bank, which were closed by state regulators on March 10 and March 12, respectively.

In the United Kingdom, authorities seized the British operations of SVB over the weekend and sold them to HSBC Holdings PLC for the equivalent of US$1.21.

Canada’s banking regulator took over the Canadian operations of SVB on March 13, the first such action since OSFI wound up the Canadian operations of Germany’s Maple Bank GmbH in 2016.

Backstory

California’s banking regulator closed SVB Financial Group’s Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) on March 10 and asked federal authorities to sell the assets amid a run on the financial institution’s deposits. It was the second-biggest bank failure in U.S. history and stirred memories of the events that preceded the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009.

SVB wasn’t a typical bank. It was formed in the early 1980s in Santa Clara and quickly became the bank of choice for the region’s burgeoning technology industry, boasting that it banked “nearly half” of U.S. startups that had received funding from venture capitalists, and that 44 per cent of venture-backed technology and health-care companies that went public in 2022 were SVB clients.

Tech was a good place to be for much of the past couple of decades. But it also meant that SVB had a lot of eggs in one basket. As inflation and interest rates soared last year, investors grew less willing to get behind companies that were putting growth ahead of profits, causing a chill among a set of companies that hadn’t had to work very hard to raise money during an extended period of ultra-low interest rates. That meant SVB didn’t have as much money coming in.

Higher interest rates squeezed SVB from the other side of its balance sheet, too. Its clients were so flush with cash that SVB couldn’t deploy all their deposits by way of new loans, which is typically the way a bank makes money. Instead, it used its excess deposits to buy bonds, which is also standard procedure for financial institutions. But those bonds steadily dropped in value as interest rates rose because there was less demand for older securities that came with lower yields.

Eventually, depositors grew nervous about the health of SVB’s balance sheet and started a run on its assets last week. That’s when regulators shut it down.

In the aftermath, some commentators dismissed comparisons to the 2008-09 financial crisis, given SVB’s troubles are related to mistakes by management and its overexposure to a single industry. However, regulators in New York state on March 12 closed Signature Bank amid signs of a run on its deposits. It was the third U.S. regional bank to collapse in five days, following SVB and Silvergate Capital Corp.

Both Signature and Silvergate were exposed to FTX, the cryptocurrency exchange started by Sam Bankman-Fried, who faces criminal charges over the implosion of his company.

Why the fuss over a few mid-tier banks?

There’s a general uneasiness in financial markets over whether the global economy can handle the sharp increase in interest rates orchestrated by the Fed and other central banks over the past year. Labour markets in the U.S., Canada and elsewhere have held up surprisingly well so far, but inflation also remains high, and history suggests the only antidote for runaway inflation is a painful economic downturn.

Fed chair Jerome Powell shook traders on March 7 when he said better-than-expected economic data meant he would have to keep raising interest rates to offset inflationary pressure. Previously, he had indicated that he thought the worst was over. The zigzag caused some investors to lose confidence in the central banks’ ability to snuff out inflation without causing a recession. In other words, plenty of people were waiting for another shoe to drop and are now betting SVB was it.

Even if the negative takes on SVB are wrong, there’s no denying the bank’s troubles herald a difficult period for lenders. Bigger banks with more diverse sources of revenue face little risk of collapsing, even if there’s a recession. But many will be caught in the same jam that squeezed SVB: less money coming in, while assets on their balance sheets deteriorate in value. Most big banks should be profitable enough to survive, but those profits will shrink for a period of time. Smaller lenders that are overly dependent on single industries or businesses might not be.

Washington was unwilling to take its chances on the optimistic scenario. In a series of extraordinary actions that brought back back memories of the 2008-09 financial crisis, the Fed and the Biden administration extended rules that were put in place to govern too-big-to-fail banks to cover smaller SVB and Signature, declaring that depositors would be “fully” protected.

What about Canada?

Canada’s federal banking regulator took control of SVB’s Canadian operations over the weekend, ending some of the unease over what might become of deposits that local technology companies had left with the Toronto-based branch.

Peter Routledge, the superintendent of financial institutions, stressed that no individual Canadians banked with SVB, so any fallout will be limited to technology companies and venture-capital funds. According to filings with OSFI, SVB had a loan book totalling $435 million in Canada and reported $864 million in total assets here as of the end of 2022. The country’s biggest banks can easily fill the gap.

Still, Canada’s tech entrepreneurs are uneasy. They have long complained that the stinginess of the country’s risk-averse banks was a barrier to Canada taking full advantage of the historic shift to a digital economy and greener sources of energy. Many welcomed SVB’s arrival in 2019 as both a new source of lending and a competitive jolt to Canadian lenders.

“While there is an immediate impact on Canadian companies that deal with SVB, the longer-term impact is the loss of a globally competitive and technology-company focused banking service,” Jim Hinton, a patent lawyer who works with many technology companies, said in an email. “SVB forced Canadian banks to be more competitive and savvier when providing services and understanding the needs of technology companies.”

It might be the wrong moment to determine whether Canada’s big banks will provide the kind of support that tech startups enjoyed from SVB going forward. Their stocks were all trading lower as of March 14 compared with five days earlier, dragging the S&P/TSX composite index down with them.

What does this mean for interest rates?

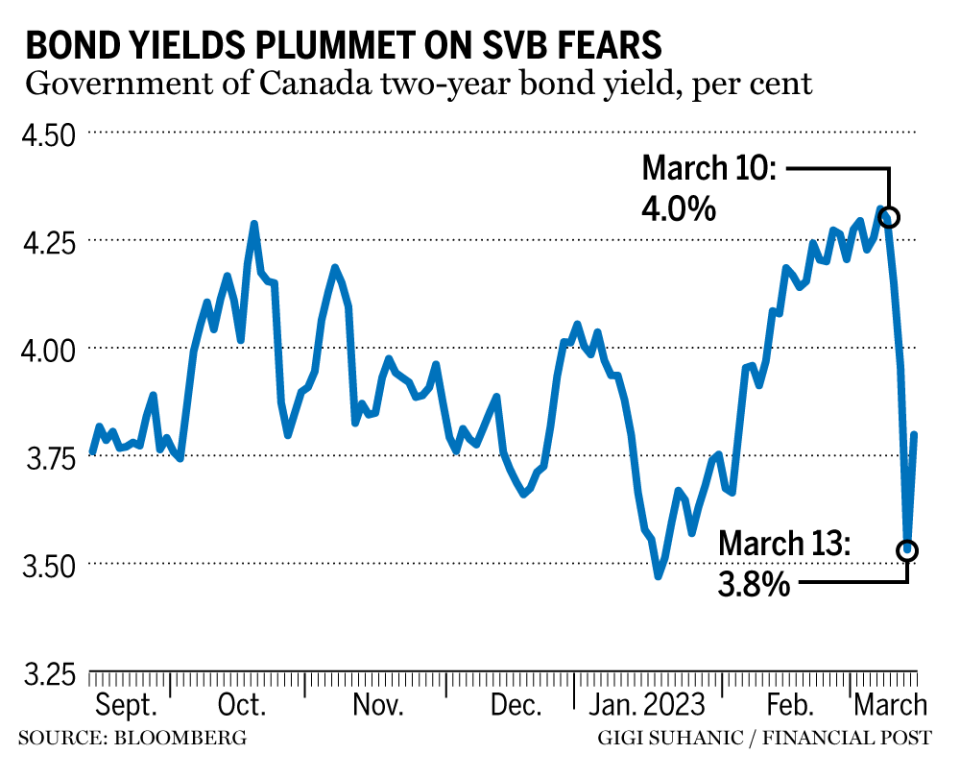

Ahead of the SVB collapse, investors were convinced that the Fed would keep raising interest rates aggressively. January inflation came in hotter than most were expecting, and Powell told lawmakers on March 7 that the “ultimate level of interest rates” will likely need to be “higher than previously anticipated.”

Some analysts reckoned the Bank of Canada would have to follow because a wider rate differential with the Fed would weaken the Canadian dollar, which would make imported goods more expensive.

Many of those bets are now off. The Fed has three jobs: price stability, doing what it can to boost employment and maintaining calm in financial markets. It’s difficult to do all three of those things at once. In fact, some economists say it’s impossible.

However, those economists don’t have a mandate from Congress to try anyway. New data on March 14 showed inflation stayed hotter than central bankers’ would like in February. Given the Fed’s responsibilities to maintain both price and financial stability, it probably will attempt to strike a balance and raise interest rates at a slower pace.

“Absent the recent turmoil in the banking sector, this data would likely have pushed the Fed to re-accelerate their pace of rate hikes,” economists at Deutsche Bank AG said in a note. “However, given the volatility, real-time risk management and the experience last year around the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine war argue for a more moderate increment or even pausing.”

With additional reporting by Reuters, Bloomberg

• Email: kcarmichael@postmedia.com | Twitter: carmichaelkevin