This Delaware town tried to take a widow's land. Then, its citizens rose up

MILFORD — When the sheriff’s department knocked on her door, Annette Billings knew what they wanted even before she opened the envelope.

It was Jan. 24, early in the morning. Her three dogs — boisterous waist-high Labradors — were bounding at the door. Billings didn’t have her glasses on yet. But even bleary-eyed she could make out the words “Superior Court” on the envelope that the deputy carried.

The deputy kept asking: Are you Annette Billings?

“I don’t know, am I?” Billings remembers thinking. “I didn’t know if I wanted to be Annette Billings right then.”

Billings, a chicken farmer for the past 30 years, does not live in Milford — a sleepy southern Delaware river city with a picturesque downtown and a history of shipbuilding.

But she knew nonetheless: The city of Milford had come for her land.

It was land where her grandparents once milked cows, and her grandchildren now play. It is land she wants to leave to her children one day, she says. Finally, she put her glasses on and sat down with the documents she’d received. She saw the fateful words: eminent domain.

“I was shaking. I was mad,” Billings said now, from her kitchen a few miles outside Milford. “It’s a terrible feeling.”

Her family’s former dairy farm, like her house, sits just outside Milford’s southeastern border. But Milford’s city charter, ratified by the state, gives Milford permission to take possession of land outside city limits in cases of public necessity.

In this case, the necessity was a bike trail.

In plans percolating for years, the city of Milford had mapped out a network of biking and running trails just outside the city, meant to connect a future 19-acre park to both the city and a new crop of densely uniform housing developments outside town with names like “Watergate” and “Windward by the River.”

Billings’ snaking 8-acre parcel of tree-thick wetlands, at the edge of her family’s former dairy farm, was the missing piece the city needed to fulfill an idyllic municipal vision of bicycles and swimming pools and pickleball courts.

For years, city officials had tried to buy Billings’ land. They’d bought her brother’s neighboring 19-acre plot in 2021 for $550,000 to form the proposed new park.

But stubbornly, Billings refused to sell her plot. She rebuffed multiple attempts — and finally told city officials to stop asking.

They stopped asking. In September 2023, the City Council instead voted to take the land in a process called condemnation. The city would get the land, and Billings would be reimbursed $20,000, a figure the city has since called generous.

Billings received no notice of the September vote on her land until a deputy showed up at her door, she said. She calls $20,000 for 8 acres not generous, but insulting. She had privately assessed her family land at about $50,000 an acre in 2007.

Billings tried to find a lawyer but didn’t know how. No firm would take her case. Finally, someone at her church gave her a phone number. It was a local firebrand of a radio host named Dan Gaffney.

Call this number at 6 a.m., she was told. And so she did.

“They tried to bamboozle me,” she told Gaffney on his radio show Feb. 5, saying the city wasn’t being honest in their dealings.

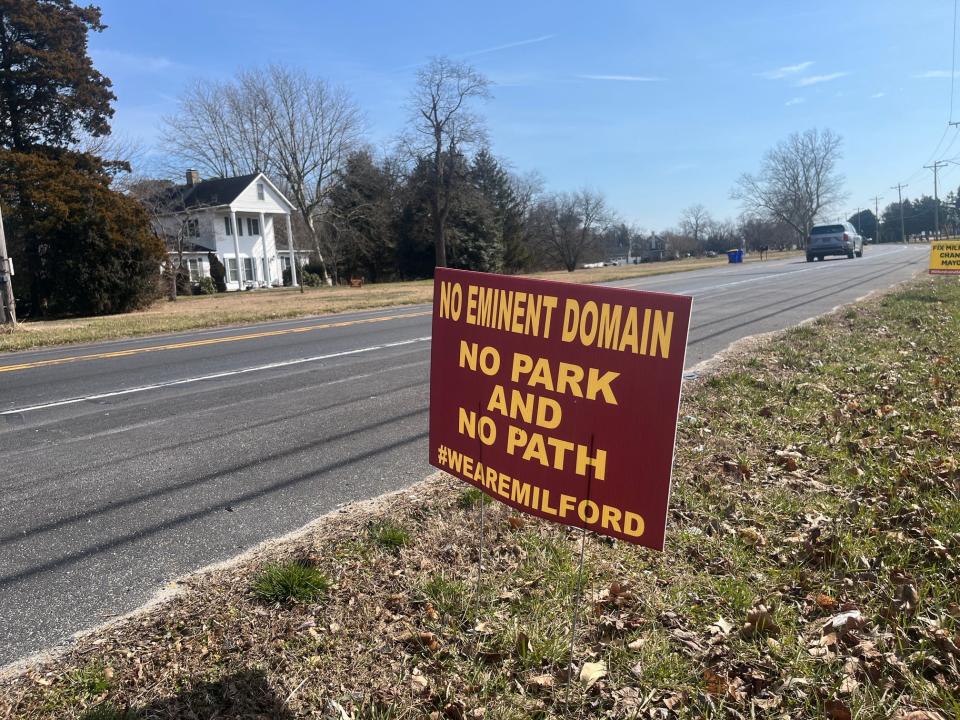

The rest is town history, setting off what locals call the biggest controversy Milford locals say they’ve seen in years: a citizen uprising over the eminent domain proceedings that has led to protests at Town Hall, and threatened to uproot the town order with a new slate of candidates for the City Council.

The case has also led to a newfound source of community for Milford, Billings said.

Annette Billings case has become a lightning rod in Milford

The city of Milford is by all accounts a quiet place. The sidewalks of its picturesque downtown stood serene and mostly empty on a recent February weekday, save for the steady foot traffic in and out of a little Puerto Rican bakery cafe called My Sister’s Fault.

But Billings’ plight has struck a raw nerve in a fast-changing city whose population has about doubled since the turn of the millennium.

In 2000, the city had just 6,700 residents. Now, it’s up to around 13,000, expansion that has mirrored rapid growth all over southern Delaware, as previously rural tracts have sprouted into rowhomes and suburban-style infill.

“Your charming little town is getting dangerously close to becoming just another run of the mill sprawling conglomerate of single family homes where nobody even wants to know their neighbor,” warned Milford resident Larry Passwaters at a City Council meeting on Feb. 12.

That day, he was among a hundred or so citizens who flooded the council meeting to voice their discontent with Billings' eminent domain case.

“If this was a Hallmark movie,” Passwaters told the City Council, “you’d be the bad guys.”

Among those upset was state Sen. David Wilson, who said he didn’t know why the city of Milford would go after land outside city limits.

Some public commenters declared the process of eminent domain as indecent or immoral. Others, without any particular evidence, have linked the attempted condemnation of Billings’ land to proposed transitional housing for the homeless, or to the city’s presumed expansionist impulses. A series of modest annexations have expanded the town’s borders by about 60 acres since 2018.

Eminent domain attracts conversation and media attention

Ask a person in Milford about Annette Billings, and they tend to have an opinion on the case.

One sidewalk passerby, a lifelong Milford resident, believed the city was trying to cheat Billings out of a fair price. The next, a former facilities employee at the University of Delaware, figured everyone probably blew the situation out of proportion.

“It’s the biggest thing to hit Milford since … ever,” said Angela Kalesis, a bartender at downtown’s Milford Tavern, who says these days even high school students talk about the case at school. When’s the last time you heard of high school students talking about city council? Kalesis mused aloud.

After a pint or two in late February, her patrons walked out of nearby Milford Tavern en masse to give the city government a piece of their mind, Kalesis said — the first time she’d seen her customers erupt with a sudden civic conscience.

And then there’s that billboard. At the southern edge of town, a billboard on land dotted with signs for local Realtor Jamie Masten had the character of a Wild West wanted poster.

“WANTED MILFORD CITY COUNCIL — ATTEMPTED THEFT,” read the billboard, which went up in mid-February. The billboard showed head shots of Milford’s mayor and its city manager, alongside the seven members of the City Council who'd voted to appropriate Billings’ land.

“City of Milford is taking local widow’s land… Stop the Madness,” read the billboard, erected within view of the city solicitor’s office.

Masten has not responded to inquiries about the billboard, but posted his dissatisfaction with the town’s actions on his Facebook account. Billings was his neighbor, he wrote, and Milford should respect a woman’s right to say no.

The billboard became a curiously viral phenomenon, appearing on TV news stations from Maryland to Philadelphia. Local outlets in Milford, meanwhile, offered day-by-day coverage of each twist in the Billings saga.

Milford officials say they are enacting the will of voters

Milford city officials, for their part, say nothing nefarious is afoot. They were merely responding to taxpayer wishes for more green space, desires that residents had expressed in 2021 during the city’s comprehensive planning process.

“Over the last four years, City Council and Staff’s only interest in pursuing the project was with the intent of providing open space and walking/biking paths, as well as other passive and active recreational opportunities for not only now, but far into the future,” read a statement from the city on Feb. 21.

Without her land, the new park would not be easily accessible from the city.

“That sounds like a you problem, not a me problem,” Billings said she told them. The city’s misjudgment in acquiring landlocked property should not take away her rights as a property owner, she says.

The city's lawyer, David Rutt, argued that Billings is fighting dirty by pleading her case publicly with what the city calls misinformation. Indeed, Billings had speculated broadly about the city's intentions on her initial radio appearance with Gaffney.

In filings at Sussex County Superior Court on Feb. 19, Rutt wrote that Billings has engaged in an “unfettered and unwarranted media blitz” since being served notice that the city intended to take possession of her property, and that media coverage had led to harassment of public officials.

Billings denies that the media was her first resort.

“I’m not a public speakin'—I'm a farmer,” she said. “I don't talk. I work.”

But lawyer after lawyer turned her down at first, she said. Her attorney, Ron Poliquin, became aware of her case, and offered to take it, only after her initial radio appearance.

Eminent domain cases outside city limits are far from unusual

Perhaps the aspect of the case that has drawn the most attention is that Billings’ property is not within Milford city limits, and yet is subject to eminent domain by the city.

But this practice is far from uncommon, said Robert McNamara, deputy litigation director of public interest law firm The Institute for Justice. The firm handles civil liberties cases all over the country, including in Delaware, on matters that include eminent domain.

“City leaders are, unsurprisingly, perhaps more willing to condemn land that belongs to people who cannot vote against them,” McNamara said. He notes that eminent domain outside municipal limits is most commonly used for things like roads and power lines, in states such as Delaware that don’t prohibit the practice.

Unlike many states, Delaware does not allow eminent domain on behalf of private enterprises such as casinos, but only for public use and the public good.

But the public good can be quite broadly interpreted. Milford’s city charter asserts its ability to condemn land for any municipal purpose whatsoever, “within or without the limits of the City.”

In Delaware, Milford is hardly alone in asserting this legal power. From Wilmington to Newark to Bethany Beach, most cities in Delaware whose charters were reviewed by the News Journal reserve the right to take land by eminent domain, both inside and outside city limits.

In general, these charters expressly require that just compensation be given when taking possession of property. Some, such as Wilmington’s, offer fairly tight proscriptions on using eminent domain — restrictions the city tried to fight in a failed bid to gain greater authority to take possession of "blighted" or vacant buildings in 2022.

More: Why Wilmington wanted expanded eminent domain authority to seize vacant property

Other charters, such as Milford’s and Dover’s, assert nearly no limitations. Bethany Beach’s charter specifically enumerates that it can take possession of any property, inside or outside the city, for the purpose of constructing paddleball courts, among a great many other things.

Because eminent domain powers are often broadly described and difficult to defend against, he said, defendants are often reduced to fighting over what constitutes just compensation, McNamara said.

“I have seen it repeatedly, in my own practice, for governments wielding eminent domain to act as if their powers are infinite,” he said.

Annette Billings prevailed in Milford, after public uprising

At least for now, Annette Billings will not have to try her chances in court.

In a Feb. 19 legal filing, City Solicitor David Rutt argued that Billings’ hearing should happen speedily and without delay, on the originally scheduled date of March 1.

Poliquin, Billings’ lawyer, argued that he needed more time to sort out the particulars of the case, and that a bike path is hardly an exigent city need that demands haste.

In petitioning the court to deny Poliquin additional time, Rutt made an argument Poliquin called unusual. Rutt argued that if the case didn’t wrap up soon, the building public pressure would be unfair to elected city officials who are up for re-election on April 27 of this year.

Elected officials' non-comment on a hot-button issue, while litigation proceeds, could “permit the continued attacks to occur without response,” Rutt argued, presumably giving an advantage to their opponents in the election.

Poliquin said he had “never seen this type of justification” for contesting a court continuance.

At least four of those council members are up for election in April, as is the town's mayor. Since the Billings’ case came to light, multiple townspeople have enrolled to run against sitting council members.

On Feb. 21, the city released a three page document outlining the city’s position, describing the proposed park's accordance with the city’s comprehensive plan, and its purpose in providing green space. The document also described Billings’ refusal to cooperate, over years of city requests for her land.

That same night, the City Council met for a special closed session to discuss litigation. As at every public meeting, public comment was allowed.

Again, the public arrived in force. At least one commenter seemed at the edge of tears. One called the councilmembers "domestic enemies." Ed Williams, a government acquisitions professional from the nearby beach town of Lewes, drove up to say he believed that Milford had not followed the appropriate federal and state guidelines — nor conducted the requisite wildlife studies.

Council receded from view, then returned with a surprise: They voted to terminate the eminent domain process. Billings would keep her family's land.

“I do not condone the notion of taking land unjustly,” said Councilwoman Katrina Wilson in a statement, before reversing her previous vote and moving to terminate eminent domain. She said she'd been moved by Billings' testimony about her family's land, and drew parallels to generations of unjust actions against people of color.

After the vote, Poliquin, Billings' attorney, said it was the people of Milford, and the court of public opinion, that had prevailed in his client's case. In an order signed Feb. 27, the city dismissed the eminent domain case and agreed to pay Billings' legal fees.

The 19-acre park outside Milford will still be built, said Milford City Manager Mark Whitfield. But the trail connecting that park to the city, and to new housing developments outside the city, will no longer exist.

Billings, for her part, says she's thankful for the people of Milford who fought on her behalf.

"The people really just did this. The people came together," she said. But she's shaken by the ordeal. On Feb. 22, the morning after receiving notification that the city’s litigation would stop, she found herself just sitting frozen in her truck, not moving or turning the ignition.

“I’m still in shock. I can’t sleep,” Billings said, finally, after opening her truck’s door to speak. “Ever since my husband died, I just feel like I’ve been kicked around. I need to stop complaining, I realize that. I need to be grateful.”

Matthew Korfhage is business and development reporter in the Delaware region covering all things related to land and money: openings and closings, construction, and the many corporations who call the First State home. Send tips and insults to mkorfhage@gannett.com.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: Delaware citizens rose up after Milford tried to take a widow's land