By denying claims, Medicare Advantage plans hurt rural hospitals, say CEOs

For decades, Rose Stone counted on the Alliance HealthCare System in rural Holly Springs, Mississippi, for her medical needs. But after she retired and signed up for a Medicare Advantage plan, she was surprised to learn it didn’t cover her visits to nonprofit Alliance, the only health-care provider within 25 miles. Stone had a choice: use her own money to keep seeing her regular doctor or drive out of town to see a physician she didn’t know but whose costs were covered.

“It was a mess,” Stone told NBC News. “I didn’t go to the doctor because I was going to have to pay out-of-pocket money I didn’t have.”

Some 31 million Americans have Medicare Advantage plans, private-sector alternatives to Medicare introduced in 2003 by Congress to encourage greater efficiency in health care. Just over half of Americans on Medicare are enrolled in one of the plans offered by large insurance companies, including UnitedHealthcare and Humana.

Problems are emerging with the plans, however. Last year, a federal audit from 2013 was released showing that 8 of the 10 largest plans had submitted inflated bills to Medicare. As for the quality of care, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, a non-partisan agency of Congress, said in a March report that it could not conclude Medicare Advantage plans “systematically provide better quality” over regular Medicare.

Even worse, because the plans routinely deny coverage for necessary care, they are threatening the existence of struggling rural hospitals nationwide, CEOs of facilities in six states told NBC News. While the number of older Americans who rely on Medicare Advantage in rural areas continues to rise, these denials force the hospitals to eat the increasing costs of care, causing some to close operations and leave residents without access to treatment.

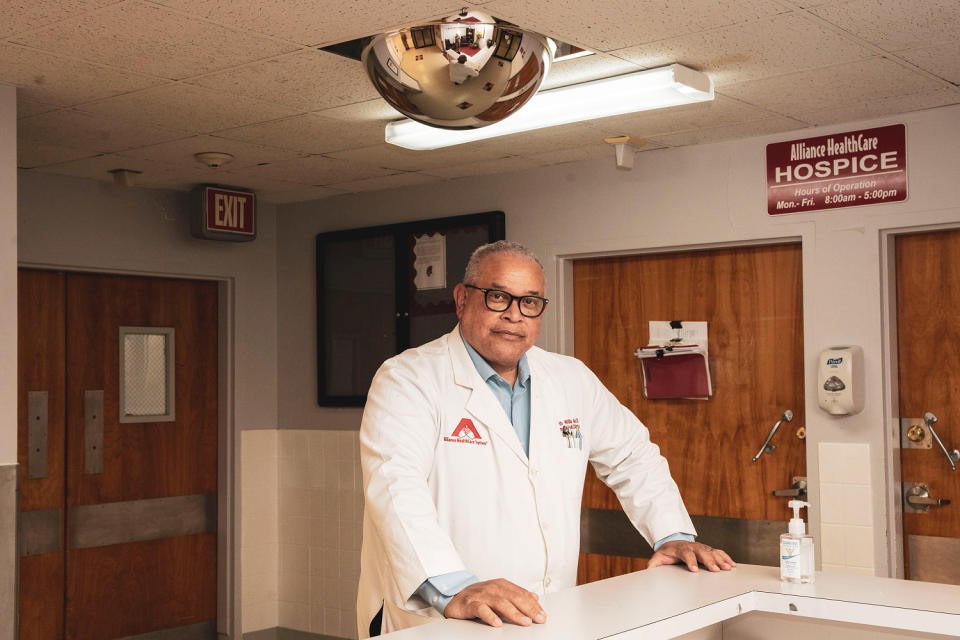

“They don’t want to reimburse for anything — deny, deny, deny,” Dr. Kenneth Williams, CEO of Alliance HealthCare, said of Medicare Advantage plans. “They are taking over Medicare and they are taking advantage of elderly patients.”

Williams is something of a local hero in Holly Springs. When the area hospital was in danger of closing in 1999, he marshaled resources and bought it to keep it open. Alliance serves a county with 38,000 people.

Still, this spring he had to shut down a long-time geriatric psychiatry program that had served the community for over eight years. Coverage denials from Medicare Advantage plans killed the program, Williams said.

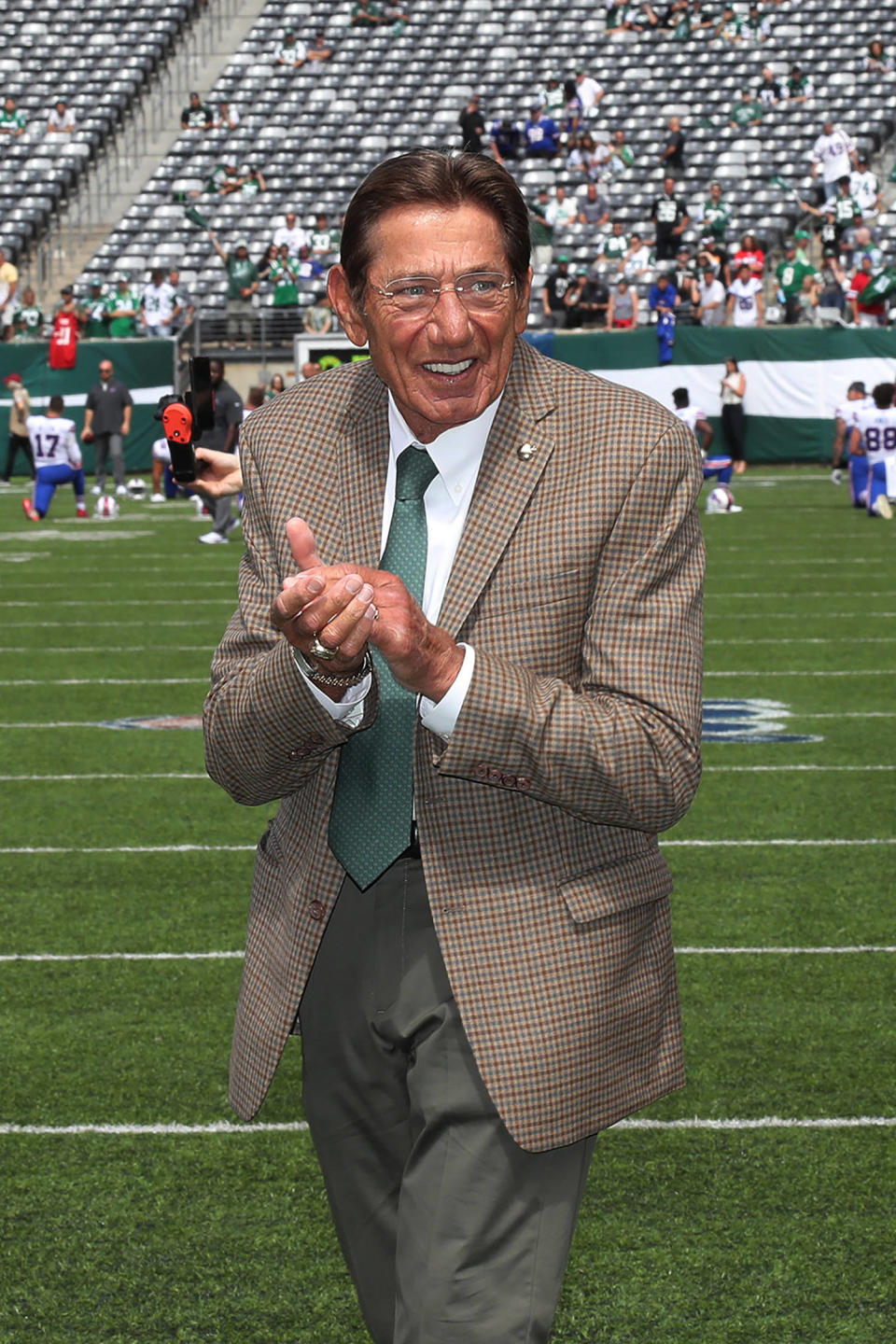

Medicare Advantage plans are sold assiduously by celebrity pitchmen — one is Joe Namath — as a better way for Americans who qualify for Medicare to get insurance coverage. Many plans add services such as dental and hearing care and wellness programs not offered under traditional Medicare, for which beneficiaries pay extra.

The U.S. government pays most of beneficiaries’ premiums to the insurers offering the plans.

If the government hoped Medicare Advantage plans would reduce the costs of care, that has not been the outcome. Medicare pays the plans 6 percent more than it would spend if plan enrollees were covered under regular, fee-for-service Medicare, the MedPAC report found. Medicare payments to the plans will total $27 billion more in 2023 than if patients were enrolled in traditional Medicare, the report projected.

A new enrollment period for the plans began this month. State insurance commissioners told NBC News they, too, receive many complaints from customers saying they were sold Medicare Advantage plans without understanding their limitations. A major complaint, said Mike Chaney, the Mississippi Insurance Commissioner: “Consumers are not aware their doctors are likely to change under the Medicare Advantage plans.”

‘We can’t pay our bills’

Medicare Advantage plans have grown in popularity in recent years, with enrollment more than doubling nationwide since 2013. One explanation: The plans are often cheaper than paying for a Medicare supplement, sometimes referred to as Medigap.

Another reason for the growth may be the significantly larger commissions the government pays to brokers selling Medicare Advantage plans. In 2024, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid will pay brokers a commission of between $611 and $762 for the first year of a Medicare Advantage plan, depending on the state, and roughly half that on annual renewals. On Medicare supplements, by contrast, brokers receive around $300 on average in year one.

Brokers selling the so-called advantage plans aren’t the only ones making money on them. UnitedHealth Group, the largest Medicare Advantage provider with 7.6 million people in its plans, generated $257 billion in premium revenues in 2022, some 13% over the previous year. A significant driver of that growth was its Medicare Advantage plans, the company’s financial filings said. Humana, the next largest provider, counts 5.3 million Medicare Advantage customers; during the six months that ended June 30, almost 80% of Humana’s $51 billion in premium revenues came from individual Medicare Advantage plans, its filings show.

Meanwhile, CEOs of rural nonprofit hospital systems in Arkansas, Colorado, Mississippi, Missouri, South Dakota and Texas told NBC News that Medicare Advantage plans repeatedly refuse to reimburse them for the care they provide. Some 170 rural hospitals are at risk of closing in those six states alone, according to a report from the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, a nonprofit advocacy organization.

While there are multiple reasons for rural hospitals’ financial woes, coverage denials from Medicare Advantage plans play a big part, said Harold Miller, president of the Center that conducted the study. For years, Medicare Advantage plans had been rare in rural areas, now they are becoming ubiquitous. In 2022, enrollment in Medicare Advantage plans grew 13 percent in rural areas versus 7 percent in urban zones, according to the MedPAC report.

Mary Beth Donahue, president of the Better Medicare Alliance, an advocacy group that supports Medicare Advantage plans, said in a statement: “We acknowledge the challenges facing some health systems, but we need to ensure coverage is maintained for millions of seniors. As Medicare Advantage continues to grow, it is essential that hospitals provide access for seniors and people with disabilities who rely on this program.”

A UnitedHealthcare spokeswoman said in a statement, “Over 6,000 hospitals participate in our UnitedHealthcare network, and we have built collaborative relationships with them to help ensure we are meeting our shared goal of providing quality care to the people we serve.”

By law, Medicare Advantage plans are supposed to base their reimbursements on Medicare rules. But there’s room for interpretation, says the Department of Health and Human Services. For example, insurers can use their own clinical criteria to determine whether to authorize or pay for care. A report last year by the department’s Inspector General found that in June 2019, the 15 top Medicare Advantage plans denied authorization for 13 percent of claims that had met Medicare rules. The plans also denied payment for 18 percent of claims that met Medicare coverage and billing rules, the report said.

Even when the plans pay, they reimburse providers far less than traditional Medicare, rural hospital CEOs and doctors told NBC News. The plans are effectively rationing health care, these providers said.

For example, the hospital officials cited specific cases in which plans take a week to approve care but agree to pay only for a three-night stay; deny coverage after approving it, clawing money back from hospitals; or contend a provider is “out of network” when it isn’t. They also deny routine tests and refuse to pay for rehabilitation, saying patients should go home before their doctors think it’s wise.

“Any study we order — X-ray, CT scan, MRI, stress tests — they’re going to deny,” said Craig Pendergrass, a doctor at Ozarks Community Hospital, a nonprofit critical access hospital in Gravette, Arkansas, in the northwest corner of the state. “With straight Medicare we just schedule it.” He estimated that his staff spends one-quarter of each week trying to persuade the plans not to deny the tests or treatment.

Large hospital systems with big staffs can dedicate time and energy to fighting claims denials, the American Hospital Association says. Small rural hospitals cannot. In response, some smaller systems are starting to reject Medicare Advantage plans. This summer, Jason Merkley, chief executive of Brookings Health System, a highly rated nonprofit hospital chain in South Dakota, stopped accepting the plans because of coverage denials and pre-authorization problems. Only a small percentage of the system’s patients had Medicare Advantage plans, Merkley told NBC News, but the effort required to battle the denials was considerable.

A Humana spokesman provided this statement: “In our Medicare Advantage hospital contracts, Humana pays rates, on average, that are above fee-for-service Medicare rates. Moreover, the fee-for-service Medicare reimbursement model is focused on patient volume and the quantity of services provided, whereas we are focused on delivering better outcomes for patients.”

In mid-September, Samaritan Health Services, a five-hospital system in Oregon, said it ended its contract with UnitedHealthcare, including its Medicare Advantage plans. “United Healthcare’s processing of requests and claims has made it difficult for Samaritan to provide timely access to the appropriate care to United’s members,” the system said.

Refusing to accept Medicare Advantage plans is not an option for hospitals with many plan customers and whose facilities are the only ones in their rural areas, the CEOs say. If they stopped accepting the plans, their communities would have to forego local health care.

“We’re a system with a proud history of taking all patients, insured or not,” said Paul Taylor, CEO of the 25-bed Ozarks Community Hospital. “But this makes it really difficult for us to continue to care for at-risk patients. We can’t pay our bills.” Medicare Advantage plans make up 40% of his reimbursements now, up from 20% a few years ago, he said.

Taylor recently conducted a two-year study of what his hospital received treating traditional Medicare patients versus what it received from Medicare Advantage plans. He found that the plans paid $4.5 million less than he received under Medicare for the same treatments. That’s roughly what his facility generates in revenues each month.

Ozarks Community, which serves approximately 30,000 people, narrowly averted a bankruptcy filing this spring, Taylor said. He is selling assets to stay afloat.

$29,458 of care denied

In late August, a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and Covid arrived at San Luis Valley Health Regional Medical Center, a 49-bed, level 3 trauma center in Alamosa, Colorado. The nonprofit hospital serves a six-county region in south central Colorado that’s home to about 50,000 people. Roughly the size of Delaware, the area is one of the poorer in the state, said Konnie Martin, San Luis Valley Health’s chief executive.

The doctor handling the patient recommended admitting her to the hospital, but her UnitedHealthcare Medicare Advantage plan balked. They agreed to pay only for “observation” of the patient, a lower standard of care that generates much smaller reimbursements.

The facility went ahead and treated her as an inpatient for two weeks, a stay that cost $29,458, all of which San Luis Valley Health absorbed, it said. Had the Medicare Advantage plan agreed to cover the claim, it would have paid one-third, the hospital estimated.

“This is the norm — they push back on people to try to keep them out of the hospital or delay their hospital care,” Martin said. The hospital’s staff has to spend time resubmitting claims, she added, saying: “It costs us 2 or 3 times the amount of labor and investment to collect on one claim.” Her staff provided documentation of four recent denials of coverage by United Healthcare in one week.

The coverage denials the CEOs described to NBC News are similar to those found in last year’s Health and Human Services report. They included erroneous rejections of MRIs and CT scans, paying only for “observation” rather than inpatient care, denials of long-term acute care, rehab, lab tests and medical equipment.

The Inspector General said that “human error” and “system processing error” caused most of the denials by Medicare Advantage plans. But the hospital executives NBC News spoke with say they believe the denials are a strategy by insurers to improve their profits by refusing to pay claims.

“This world of medical billing is so automated if you’re denying a claim, you’re doing it intentionally,” said Martin, of San Luis Valley Health.

UnitedHealthcare declined to comment.

The Cuero Regional Health System, a small hospital in Cuero, Texas, serves a population of 22,000. Its officials say Medicare Advantage plans often deny care based on the insurers’ internal determinations about the type of care required, overruling the physicians handling the cases. When the hospital questions a determination — called a peer-to-peer review — officials often have to argue with a physician who doesn’t specialize in the care the patient requires, said Lynn Falcone, its chief executive.

A Medicare Advantage plan recently denied a referral to long-term acute care for a patient with sepsis, Falcone said. When the family practice doctor overseeing the case asked for a peer-to-peer review, the insurance company physician defending the denial was an ob-gyn specialist. “A surgeon that delivers babies maybe isn’t used to handling sepsis,” Falcone said.

‘It had to be extreme’

Sandra Tate of Cuero, Texas, said her family’s Medicare Advantage plan created problems for her family in Feb. 2022. Her husband required physical and respiratory therapy after a 10-day stay in the ICU at Cuero Regional Health, she said; although a previous plan from Humana had paid for this treatment four years earlier, the second request for reimbursement was denied under her new plan from United Healthcare. After arguing with the insurer for 30 minutes, Tate, a former school nurse, said she was never told why.

“I pay my Medicare premiums and also my insurance premiums,” Tate told NBC News. “I don’t understand why Medicare Advantage is not wanting to pay the rural hospitals that are taking care of you.”

The UnitedHealthcare spokeswoman said the company could not comment on Tate’s experience unless she signed a waiver; Tate declined to do so.

In its financial filings, United Healthcare describes how rates paid by the government on Medicare Advantage plans can fall below what the insurer calls its “cost trends.” To combat these profit pressures, the insurer said, it “can seek to intensify our medical and operating cost management” and “adjust member benefits.”

For eight-and-a-half years, Alliance HealthCare System's inpatient geriatric psychiatry program helped older patients in Holly Springs, Mississippi, with depression and other mental health issues. The 15-bed facility offered group and family therapy as well as an inpatient program that could run from one to three weeks, said Ejerra J. Selma Dukes, its former director.

Medicare always paid for the services, Dukes said. But a few years ago, she started seeing more patients with Medicare Advantage plans declining to pay. The insurers would reject claims for patients with depression and dementia, she said, agreeing to reimburse only for those who were suicidal, paranoid or homicidal. “It had to be extreme for them to say we will allow you all to bring them in,” Dukes told NBC News.

On March 28, the program closed its doors, Dukes said, a result of the denials. “It was heartbreaking, especially with those who had been dealing with us a long time,” she recalled. “You know you can help, but you can’t bring people in for free.”

Meanwhile, Rose Stone is once again receiving care at Alliance HealthCare System. She junked her Medicare Advantage Plan and returned to Medicare, with a supplement. “Everything is fine now,” she said.

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com