Facebook’s Chris Cox was more than just the world's most powerful chief product officer

In late 2003, during his senior year at Stanford, Chris Cox, the future Chief Product Officer at Facebook (FB), embarked on a 78-day National Outdoor Leadership School expedition to Patagonia, in Chile.

The trip began with sea-kayaking in driving rains along the Chilean coast and then progressed to mountaineering in white-out, blizzard conditions in the Andes, Cox recalls in an interview. There, the students learned glacial traversing and how to build buffers around their tents to ensure they wouldn’t get snowed under in their sleep.

Asked what he learned from this trip, Cox inquires if I’ve ever seen the film “Meru.”

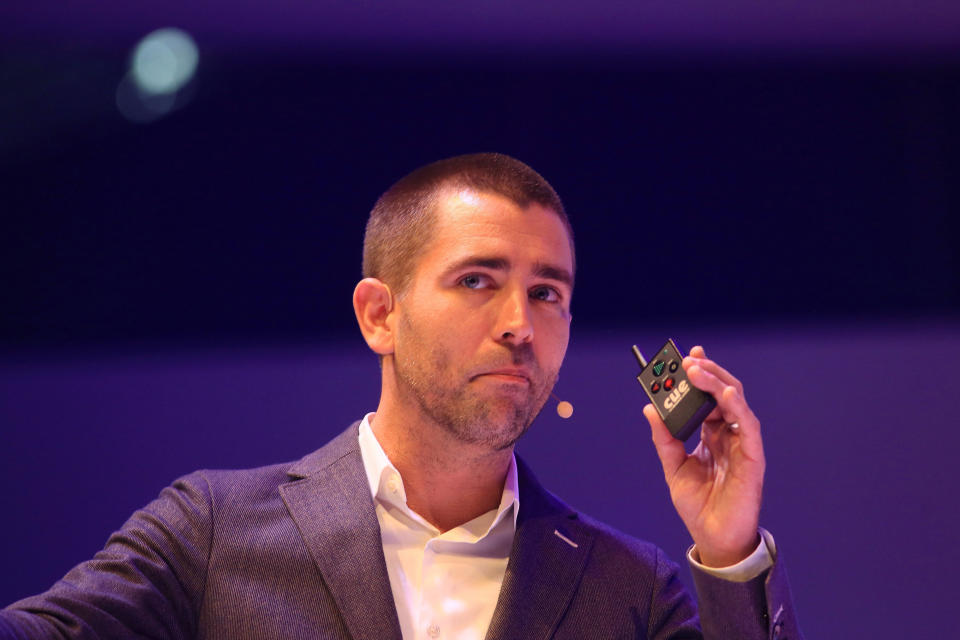

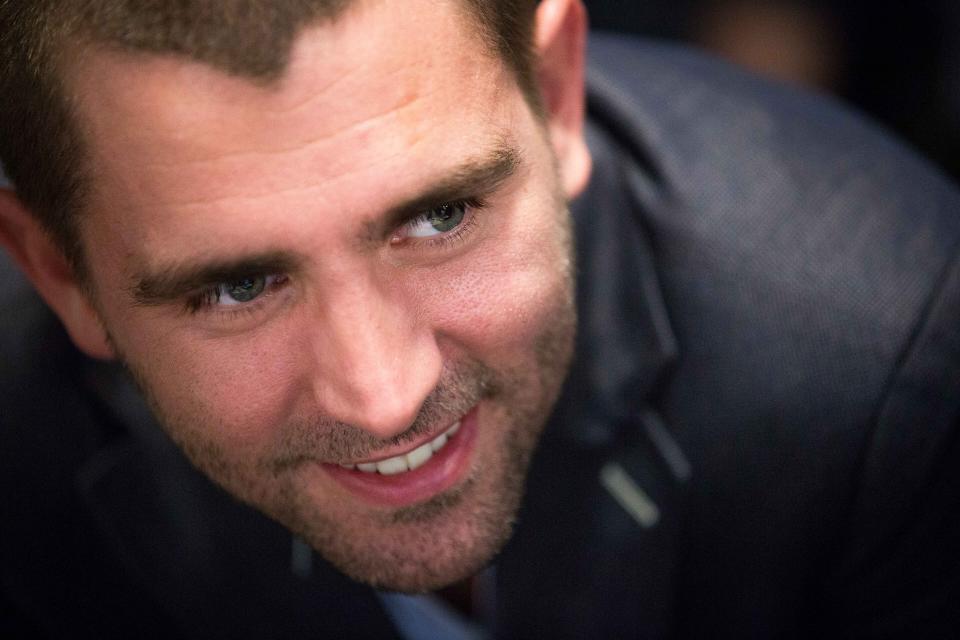

“You’ve gotta see this film,” says Cox, who is 5’10”, fit, good-looking, with a crewcut. It’s about three mountain climbers ascending an unscaled summit in the Indian Himalayas. The movie was shot and codirected by Jimmy Chin—a friend of Cox’s—who is also one of the climbers. “One of things you notice about Jimmy is: He’s always buoyant,” Cox says. “In even the worst conditions, he’s helping everyone focus on moving forward. You have to be creating progress and motion and buoyancy. That’s a lesson that I have found really useful in all the really hard parts of the Facebook experience.”

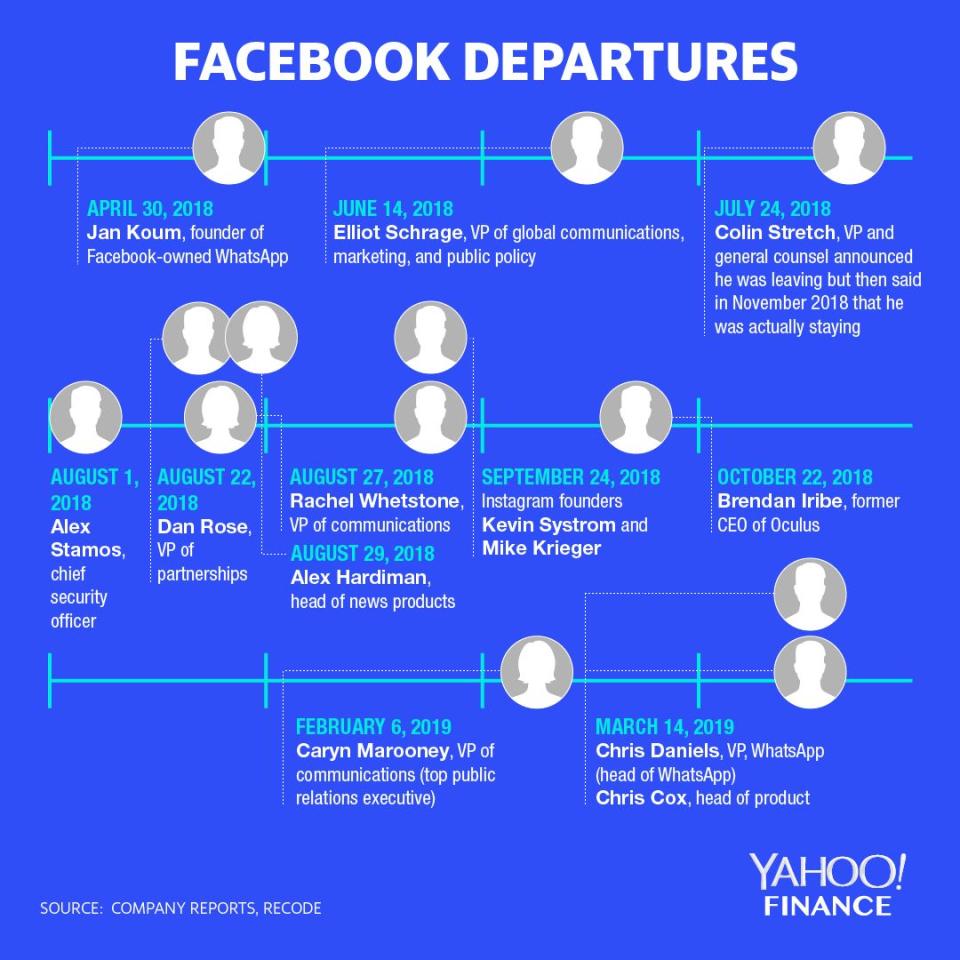

Last month, Chris Cox, 36, decided to leave Facebook after 13 years—his entire, post-university, working life. He joined in November 2005, when Thefacebook, as it was then still called, was only open to college and high school kids—about 5 million of them. He was the thirteenth engineer, he believes, and employee number 40 or so. In 2008, he became the company’s vice president for product and, then, in 2014, its Chief Product Officer, making him the company’s third most powerful executive. Last May, his portfolio was broadened to include Facebook’s family of apps—Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger. As Wired’s Nicholas Thompson noted at the time, the move effectively put him in charge of product for “four of the six largest social media platforms in the world.”

From 2014—when his earnings became subject to SEC disclosure—through the end of last year, he earned more than $390 million in salary, bonus, and vested stock awards. (Some of those restricted stock awards reach back to 2009, and reflect Facebook's soaring share value since then.)

Even so, by officially relinquishing the CPO post in April, Cox walked away from more than $170 million more in unvested stock, according to the filings.

‘Artistic differences’ with the CEO

He is leaving because of what he calls, only half jokingly, “artistic differences” with CEO Mark Zuckerberg, he says. “But I respect and care about Mark so deeply,” he adds, “that I would never really want to get into more detail than that.” (Below is his Facebook post announcing his departure.)

According to three people familiar with his thinking, he disagreed with Zuckerberg about his decision to integrate the Facebook “family of apps”—Facebook, Messenger, Instagram, and WhatsApp—and also with Zuckerberg’s more surprising and dramatic pivot, announced March 6, to create more end-to-end encrypted spaces on the platform for individual and small group communications.

As for the integration, Cox felt many end-users preferred the diversity of choices available today, according to the sources, though he also recognized the logic behind Zuckerberg’s approach—efficiency for the company and greater convenience for some users.

His precise qualms with end-to-end encryption remain unknown to me, although such technology, by placing conversations beyond the reach of Facebook itself, makes it impossible for a company to patrol hate speech, propaganda operations, terrorist plotting, and other bad acts on its platform—a major focus for Cox in recent years. (At the same time, it better protects users’ communications from intrusions by hackers or surveillance by autocratic governments.) When Zuckerberg unveiled his new product directive, he promised the near impossible, vowing to provide encrypted spaces while also protecting society’s safety. Had Cox stayed, his job would have included squaring that circle.

‘Vast company authority’

The meaning of the CPO title in Silicon Valley is an elusive one. “It’s a title that did not exist much at all until recent years,” says David Kirkpatrick, the founder and editor-in-chief of Techonomy Media, “but is used with expediency to describe certain people who have vast company authority, who are deeply respected by company leadership, but whose responsibilities cannot be slotted into conventional definitions.”

Since at least 2014, Cox has effectively been Zuckerberg’s chief of staff for executing product strategy. But throughout his career there, Cox has been intimately involved in crafting the defining features of the company’s products, beginning with the granddaddy of them all—News Feed—which is now the personalized, real-time newspaper for about 2.4 billion people worldwide.

He has also served as the company’s key “internal ambassador,” as his former roommate and early Facebook colleague Ezra Callahan puts it. He has helped define how the company would like to see itself by leading countless “onboarding” talks to new employees, Q&A discussions, and all-hands’ meetings, and by helping shape its mission statement and core company values.

“It’s extremely hard for me to imagine Facebook without Chris Cox,” says designer Soleio Cuervo, who worked at Facebook from 2005 to 2011, “both from the technical standpoint and, probably more importantly, cultural standpoint. He contributed to its code, to the language that it used, and to how it explained itself to itself.”

After the 2016 presidential election, the world changed. Politicians, media, and popular sentiment turned on Facebook, viewing nearly everything to which Cox devoted the first 11 years of his career through a radically different lens. Though Cox himself has not been the target of criticism, his close friends, Zuckerberg and chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg, certainly have.

In addition, Facebook’s products—Cox’s bailiwick—are under the microscope, subjected to dozens of critiques. Do News Feed’s algorithms promote political polarization, amplify sensationalism, and reward hatred and lies? Does the company’s business model lead ineluctably to privacy abuses? Can its vast platform ever be adequately policed to protect elections against coordinated misinformation campaigns? Has engineering designed to promote engagement ended up promoting metaphoric—or even literal—user addiction? (The company said this week that it likely faces $3-$5 billion in liability for a Federal Trade Commission inquiry into whether its privacy practices violated a 2011 consent decree. At the same time it is reportedly the subject of a Securities and Exchange Commission inquiry in the Northern District of California and a federal criminal probe in Brooklyn, which also appear to focus on its privacy policies. No reporting has implicated Cox in those matters.)

Despite Cox’s crucial importance to this crucially important company—he has been the most important chief product officer in the world—Cox is relatively little known outside the company. And while widely hailed for his personability, he’s also “difficult to deeply get to know,” according to one long-time friend. In this article we offer the most in-depth profile to date of a gifted and still very young man, who has played a seminal role in molding a now feared and polemicized behemoth.

Cox and Facebook—he is still affiliated with the company, and will continue to play a transitional, “advisory” role for an unspecified period, he says—provided wary assistance for this article. Cox gave two interviews, although the first—an hour-and-a-half stroll around a beautiful Palo Alto neighborhood—was conducted, at his insistence, without note-taking or a recording device. Those conversations have been supplemented with interviews with 23 friends or colleagues, including five current and 13 former Facebook employees. Facebook declined to make Zuckerberg, Sandberg, or other high executives available. (Dozens did not return inquiries. Some declined to speak, citing disappointment with previous media coverage of Facebook. Even long-departed employees may be influenced by non-disclosure agreements, non-disparagement clauses, retained stock holdings, and the power of Facebook.)

‘Everything Mark wished he could be’

Among those who agreed to speak, the superlatives were thick. The most common theme was Cox’s rare melding of technological chops, business skills, and personal empathy and charisma. (He is also a talented musician, who, despite the crushing demands of the job, continued performing professionally in local reggae and Afrobeat bands until 2014, when his wife gave birth to the first of their two children.)

“He is an incredible combination of engineering-level IQ combined with EQ,” says Brandee Barker, who headed Facebook’s communications unit in the early days, from 2006 to 2010. “That makes him not only brilliant, but approachable.”

“There’s no left brain. No right brain,” says Callahan, who left Facebook in 2010 and now heads the Arrive hotel and restaurant chain, which he founded. “He’s good at everything.”

While IQ is easy to come by at Facebook, EQ is a scarcer resource. Though not typically a salient feature for a Silicon Valley chief product officer, it’s been crucial to Cox’s role.

“Mark [Zuckerberg] was the better computer scientist,” observes Callahan. But in all other respects, “Chris was everything Mark wished he could be. Chris was cool, outgoing, tons of friends, a natural performer. He had no trouble going on stage and commanding an audience.”

“Mark is obviously not the most relatable guy,” says another early Facebook employee, who requested anonymity. “Chris had the ability to connect with Mark,” he continues, “to understand what he was trying to do, and to translate that” in an inspiring way to the rest of the company. “He could humanize Mark.” (As pictured above, Cox’s farewell post to his Facebook site includes a photo of the CEO and him with arms around each other’s shoulders.)

While Facebook representatives—including Cox—emphasize that he has trained gifted executives to take over in his wake, the lost chemistry between Zuckerberg and Cox is irreplaceable.

‘Highly perceptive from birth’

Chris Cox was born in Atlanta on September 2, 1982. When he was one month old, his family moved to Chicago. Cox grew up mostly in the wealthy suburb of Winnetka.

His parents, Dan and Mary Beth, were both interviewed for this article. Dan, has sometimes been described as an actuary, but that doesn’t do justice to his own Type A career. Born into a blue-collar family near Burlington, North Carolina—Dan’s own father worked in a knitting mill—Dan was hired by Aon in 1982 to start what became Aon Consulting. By 2000 he had built it into a $750 million business, with over 5,700 employees in 18 countries. After leaving Aon, he ran several other enterprises, selling the last to JPMorgan in 2006, and retiring as a JPM managing director in 2010.

One thing Cox learned from his father, he remarks, is that he should always be among the first in the office each morning, no matter how high he rose in the organization.

Cox’s mother, Mary Beth, stayed at home until he reached the seventh grade, and then worked as a high school English teacher.

Cox was the youngest of three kids. His sister and brother were six and eight years older, respectively, and Mary Beth believes the age gap contributed to Cox’s early maturity.

“He was highly perceptive from birth,” she recalls, “and we didn’t talk down, baby stuff, to him.” He closely watched what his older siblings were doing, and played with the family’s Apple II GS from an early age.

When he was about six or seven, Mary Beth noticed that, after Cox’s older sister took her piano lessons, he would go to the keyboard and try to play what she had been working on. Mary Beth got him lessons from their church organist—mainly classical music and hymnals.

By the time he reached sixth or seventh grade, Mary Beth noticed that he was improvising. “I guess you would call it jazz,” she says.

When he got to New Trier High School—one of the most affluent public schools in the country—he became the keyboardist for one of its jazz bands, and started a second set of lessons each week, just for jazz. Though Cox played freshman tennis, music soon crowded sports from his schedule.

“It was an obsession,” Cox recounts. “Everything I heard I wanted to play.” He played in several rock bands and picked up guitar and drums on his own.

Academically, Cox was placed two grades ahead in math, but his favorite class was a Great Books course, taught by Raissa Landor. Seventeen years later, in 2017, when he went back to New Trier to accept an alumni award, he vividly recalled one of her assignments. She had asked the students to debate the existence of God—not as an idle rhetorical exercise, with assigned positions—but discussing their actual views.

“For 50 minutes on a freezing, snowy day in Winnetka we talked loudly over the buzzing of the radiators and the fluorescent lights. … For so many of us it was the first time we’d been challenged to arrive at our own conclusions about God, rather than taking notes or dictations on another’s truth. … The lesson that day wasn’t about God. … It was simple: Consider the great questions. Debate them earnestly, but listen carefully to each other. Arrive at your own conclusions based in reason and in experience. And then ask what this means for your role in the world, and do something about it. Go off and fight for what is fair and good.”

In an interview, Landor remembers Cox as a “natural leader” who “never dominated” others. She remembers a point halfway through the year, when some of Cox’s classmates were growing frustrated with the fact that there were no right answers to the questions she was posing.

“Chris spoke up,” she recalls, “and in a very articulate, compelling way said, ‘You’re missing the whole point of this class. Ultimately we have to decide what are the values to draw from these texts and to apply to our own lives.’

“The atmosphere changed,” she said. “I felt he’d really made a difference.”

“Aristotle says that the prime quality of a good prince is magnanimity,” Landor continues, “meaning generosity, empathy—whatever.” That’s the quality he possesses, she says. “Whatever he does, people will turn toward him. Will feel heard. And, when called for, he’ll help them see things in a different way.”

A serious student with a love for Afrobeat

Stanford offered freshmen its own optional, intense, one-year variant on a Great Books program. It was called Structured Liberal Education, or SLE (pronounced “slee”). Cox enrolled in it. It had been set up in the 1970s by Mark Mancall, a history professor who specializes in the religions and culture of central and southeast Asia. All 80 or so SLE students lived in the same dorm, ate in the same dining hall, and had close interactions with the faculty who led it, including Mancall.

Mancall, now 86, soon bonded with Chris, and remains a mentor and close friend today. “Chris took almost every course I ever taught,” he recalls, and went on an academic trip to Bhutan that Mancall organized.

He was “a very serious student,” according to Mancall. “I don’t mean dull. Never dull. Took issues seriously. Had a strong sense of values and would argue for his values.” Mancall felt that the depth of Cox’s grasp of both intellectual and technological issues was rare. “Here in the Valley, particularly, many of us feel the intellectual side has sort of slipped away.”

Cox remembers learning from Mancall the importance of words and language, beginning with one of the first texts they pored over, the Old Testament.

“God speaks the world into existence: ‘Let there be light,’” says Mancall, explaining what Cox is alluding to. “Language is what creates the world.”

On the musical side of his life, Cox took off in a new direction at Stanford. The university has long featured a Taiko Drum ensemble, a Japanese artform that combines music, martial arts, and performance.

“It was stunning,” Cox says, remembering when he first saw it. “I said: I want to be part of that.”

About a hundred students auditioned for about five open slots. “I was good rhythmically, but I didn’t look that great on stage,” he says. He made the cut, and eventually became co-artistic director. The other artistic director was a biology student named Visra Vichit-Vadakan.

“Visra had studied Thai sword fighting, so she looked amazing on stage,” he recalls. Vichit-Vadakan came from a prominent Thai family that professor Mancall already knew well. (Her grandfather, Luang Wichitwadakan, was a statesman, playwright, poet, and historian who is widely credited with having helped modernize Thailand.) Vichit-Vadakan, too, went to Bhutan with Mancall. Cox and she became friends, best friends, and, in 2011, husband and wife.

After SLE ended, Cox majored in symbolic systems and artificial intelligence. At Stanford, computer science is part of a rigidly defined engineering program, while “symsys” permits a more flexible curriculum, including courses in linguistics, language philosophy, and neurology, which are relevant to building artificial intelligence. (Other notable symsys grads include LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman, former Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer, and Instagram cofounder Mike Krieger.) Cox was particularly interested in natural language processing—teaching computers to understand written and oral human language.

It was only then that Cox began to learn software programming. He took to it quickly, though. “You can do this,” he remembers his instructors telling him.

At the same time, his musical experiences further diversified. He played in campus rock and cover bands, but also with a Stanford blues prodigy, David Jacobs-Strain. In Cox’s senior year Jacobs-Strain invited him to tour with him—a stint that included opening for Taj Mahal one night.

By then, Cox had also become involved with Highlife and Afrobeat music—West African jazz artforms. After learning that some legendary players lived in Oakland, he sought out lessons from a couple of them—Baba Ken Okulolo and Adesoji Odukogbe—and performed with their bands. Odukogbe had played with Fela Kuti, one of the most revered pioneers of Afrobeat, who had died in 1997.

“It was still another way of learning about what music was,” Cox observes. “I was coming at it through jazz, classical, through the Japanese lens, and now from Nigeria and Ghana.”

Jumping forward nearly two decades, to February 2017, these experiences culminated in what Cox calls one of the highlights of his life. On a tour of West Africa for Facebook, he took a sidetrip to the New Afrika Shrine outside Lagos where he performed keyboards—Fela Kuti’s instrument—with an Afro-Beat band led by one of Kuti’s sons, Femi. (You can hear one of his performances here.)

Asked how his musical life informed his work at Facebook, he declines the bait.

“I never really directly tried to apply any of this. It’s just a completely separate side of who I am. It was a hobby turned up to 11. In another universe, I’d have been a musician.”

‘Chris didn’t want us to think he was a quitter’

Cox graduated in 2004, worked for a year as a programmer in Stanford’s natural language processing lab, and then, in September 2005, started a graduate program in the same department. He was living in an off-campus coop known as Truckin’, named for the Grateful Dead song. According to friends who visited him there, he lived in a poorly insulated, converted garage, with a mattress on the floor, spartan furniture, and a Fender Rhodes electric piano. Tibetan prayer flags were strung across the back yard.

One of his roommates, Ezra Callahan, had started working at Facebook. Callahan urged Cox to interview for a slot as an engineer. (Facebook would pay Callahan a $5,000 commission, if Cox was hired.) Cox was skeptical, but agreed to humor his friend, bicycling over to Facebook’s then offices on 156 University Avenue in Palo Alto.

For some reason, Zuckerberg was not available that week, but Cox interviewed with company cofounder Dustin Moskovitz (one of Zuckerberg’s former Harvard roommates); Adam D’Angelo (the now-founder and CEO of Quora); Aditya Agarwal (a Carnegie Mellon engineer who later became CTO of DropBox); and Jeff Rothschild, who, at 51, was Facebook’s oldest employee by far. A former Honeywell and Intel engineer, Rothschild had, by then, already founded two software companies, and was a partner at venture capital firm Accel Partners, which had just invested in the startup.

Facebook’s key challenge at the time was to convince talented young engineers to choose them over Google, which had IPO’d the year before. Google’s technological gravitas was a given, while social media was seen as frivolous—like dating sites. Plus, the dot-com crash was still fresh in everyone’s mind, so startups were suspect.

“I was driving the push to be recognized as a technology,” recalls D’Angelo. “I think I asked Chris a bunch of questions, like, ‘How would you predict what someone’s favorite music was? Or movie?’”

Another staple of Facebook interviews at that time was a description of the “social graph”—or just “graph,” as Zuckerberg would tersely call it. The notion was that society is a dynamic system of ever-shifting, variously weighted, relationships among people—friends, former classmates, family members, employers—with everyone occupying a unique place in the tangle.

“If you want to be philosophical about it, who you are as a person is a function of those relationships,” says former Facebook designer Cuervo, who interviewed the same month as Cox, and joined up the same week. Facebook was going to effectively map out this graph and, in doing so, bring people more closely together, Cuervo explains.

Cox remembers being awed by the intellects of the people who interviewed him, and fascinated by the “simple and elegant” idea of the graph. “It struck me as both obvious, and yet I’d never thought of it before. It was a collaboratively created directory of people that is up to date and interconnected and authentic, and where each person is responsible for their own representation.”

As Cuervo remembers the graph, however, there was another piece to it. The graph held the prospect of generating “an advertising platform that would rival Google’s,” he remembers. Because Facebook then had a “friends-only” privacy model—only friends could see friends’ posts—people were expected to share more intimate details about themselves than they would on other web sites. So they would be providing data that could be used to target ads with unique precision.

That aspect of the graph played no role in his thinking, Cox asserts. “Advertising had nothing to do with it,” he says, flatly.

Cox then consulted his mentors. Should he drop out of the masters program he’d just embarked upon in order to dive into this risky startup?

Professor Mancall was opposed.

Then Cox asked his parents, who were visiting in nearby Inverness, north of San Francisco, in western Marin County.

“Chris didn’t want us to think he was a quitter,” his mother Mary Beth recalls, “but we didn’t at all.

“He had been so blown away by the kind of interviewing they did,” she continues. “The problems they gave him to solve were causing him to really critically and creatively think. … Dan and I were of exactly the same mind. So often a degree is a default,” she says, suggesting sometimes people seek degrees when they don’t know what to do next. “The degree certainly didn’t mean anything to us.”

“I said, ‘Chris,’” recalls Dan, “‘You’ve made pretty good decisions up to now. I think you should probably go for it.’”

An intense startup environment

Cox started as an engineer on November 7, 2005.

“We had a lot of loud personalities,” remembers Cuervo, citing Zuckerberg, Moskowitz, Callahan, and early engineer Andrew Bosworth, who is now VP of Facebook’s augmented reality/virtual reality division. (A famously raw, internal memo Bosworth wrote in 2016, discussing the “ugly” aspects of Facebook’s business model, caused a stir when leaked in 2018; Bosworth disavowed and deleted it.)

“Although Cox was also a big, sometimes booming, personality,” he continues, “he was very well liked, well respected, very considerate. And like a really great party host, he was good at instigating comraderie and conversation between people, especially as we were scaling and growing, making sure everybody was getting along.” Many people recall Cox greeting them with a hearty, protracted “holla.”

“People forget,” he adds, “this was a really intense, startup environment.” Facebook didn’t overtake MySpace in terms of [domestic] monthly users until 2009. “A lot of people looked at Facebook and said, ‘Why are you guys even bothering? There’s already a category-winner here.’”

Cox’s first assignment was to build the feature that today seems so central that most people today can’t imagine the site without it: News Feed. Instead of having users laboriously browse between their friends’ static pages, the company would provide a feed that would periodically push out updates on what was new. So as not to overwhelm the user, though, it had to be algorithmic. It would figure out, by weighing dozens of different factors, which posts would likely be of greatest interest to which users.

“Chris was thrown into far and away the most extensive, computer science endeavor Facebook had ever embarked upon,” says Callahan.

It was a team project, but Cox and Bosworth pulled the laboring oars. (Cox is listed as a coinventor on 32 Facebook patents—13 granted and 19 pending—most of which concern iterations of News Feed. He doesn’t seem to know much about these, though. “Lawyers would come in every so often and ask us what we were doing,” he says, shrugging.)

News Feed launched in September 2006, 10 months after Cox’s arrival. Famously, it was a fiasco. Having been given no prior notice or opportunity to fine-tune privacy settings, users were horrified to see their postings broadcast indiscriminately to every one of their friends. Within four days, 700,000 people had joined a Facebook group called Students Against Facebook News Feed (SAFNF)—by far the largest Facebook group ever formed to date, according to “The Facebook Effect,” authored by Kirkpatrick in 2010, before he founded Techonomy.

Cox was crushed, he recalls, but remembers no internal recriminations, perhaps because Zuckerberg never waivered in his belief in the product. The very fact that the anti-News Feed group had formed so quickly demonstrated News Feed’s extraordinary power: users knew of SAFNF’s existence only because News Feed was alerting them that their friends had joined it.

Cox, Bosworth, and another early programmer, Ruchi Sanghvi, madly implemented a set of privacy tools within 48 hours. Thereafter, News Feed was seen as a fabulous success. As the anti-News Feed group dissipated, a vast, new group ballooned up out of nowhere. It was “Save Darfur,” a humanitarian effort to help the starving people of Sudan.

While Facebook users had viewed a total of 12 billion pages the month before News Feed launched, they viewed 22 billion pages the month after, according to Kirkpatrick’s book. Indeed, the title of that book, “The Facebook Effect,” refers to the unprecedented, breathtaking impact News Feed had in virally propagating news and spurring people to collective action—for better or for worse.

An unorthodox choice to head HR

By late 2007, Facebook was growing up as a company. It needed policies for a range of messy, nitty-gritty, human-resources issues that, as a startup, it had neglected: formalized performance reviews, career development plans, guidelines for gender issues, and so on. A conventional hire from outside the company had not worked out. Employees worried that the once hacker-inspired startup was turning into a faceless, bureaucratic behemoth.

Zuckerberg made an odd, but inspired choice. He asked Cox—a software engineer—to become head of human resources.

“Everyone knew him,” says an employee who was there at the time. “He was a very, human, charismatic person. It was a strong way of signaling that we were not turning into a corporate thing overnight.”

Before accepting the move, Cox consulted with his father. Cox recalls Dan advising, “If you understand product, HR, and finance, then you understand business.”

The thing his father remembers about that conversation, on the other hand, is what Cox told him: “He said, ‘I’ve kind of analyzed myself, and I really enjoy taking on things that I almost can’t do.’ I think that’s a pretty good description.”

While heading HR, Cox thought it would be helpful for the company to publish a mission statement and a statement of core company values.

“The values needed to reflect both the company and the founders: Mark, Dustin, and Chris Hughes,” Cox explains. He began working closely with Zuckerberg on this project, and believes it was then that the two first bonded as friends.

“You didn’t want the values to be hollow, like a top-down edict,” Cox continues. So he held four town halls to get employees involved. “The format essentially was, ‘Here’s what I’m hearing. Are we missing anything? Is this the language that rings true to you about why you’re here?” When the values were finally announced, each was read by a different employee, chosen to both exemplify the value and reflect inclusivity in terms of gender, age, department, and so on.

The original mission statement was: “Facebook helps you connect and share with the people in your life,” while the original values were: “Focus on Impact; Move Fast; Be Bold; Be Open; Build Trust.”

“Everybody in the company felt they’d participated,” Cox says, “and Mark felt [the values] were his.”

While heading HR, Cox began delivering inspirational “onboarding” talks to new employees. It became an institutional function that he continued to own ever since, right up until he announced his departure. In recent years, he delivered one almost every Monday.

In preparing for these, and trying to understand Facebook’s place in media history, he read Marshall McLuhan, the elusive Canadian media philosopher of the 1960s, who coined the phrase “the global village” and is credited with having foreseen the ascendance of the World Wide Web some 30 years before it arrived.

If videos exist of Cox’s onboardings, Facebook declined to make one available. But they have been described by others. In his 2017 book, “Becoming Facebook,” Mike Hoefflinger, a former Facebook director of global business marketing, said he attended at least a dozen of them. In the talks, he wrote, Cox could not “contain his enthusiasm for … how the work of Facebook and others is a natural expansion of the pace and scale of media that goes back to the Gutenberg press and language itself.”

A more cynical take was sketched out by former product manager Antonio García-Martínez in his 2016 bestseller, “Chaos Monkeys.” Cox weaved a “seductive narrative” with “studied and flawless spontaneity,” Martínez wrote. “He then embarked on a common trope among Valley types, framing the product in some historical continuum of prior technologies, the product currently being discussed being the ultimate and inevitable final chapter in the triumphant procession. … Facebook … was the true teleological end goal of modern media.”

(Martínez also suggests that the power of Cox’s message was not hampered by his winning physical presence. As he puts it, Cox presented “a tempered masculinity encased in a cuddly package, custom-made for female desire.”)

Cox provided his own gloss on what he had been trying to do in those talks—though with some decidedly sober, post-2016 overtones—in his farewell post in March. “For over a decade, I've been sharing the same message that Mark and I have always believed,” he wrote. “Social media's history is not yet written, and its effects are not neutral. It is tied up in the richness and complexity of social life. As its builders we must endeavor to understand its impact — all the good, and all the bad — and take up the daily work of bending it towards the positive, and towards the good. This is our greatest responsibility.”

The company’s first crucial mobile app

In 2008 Cox returned to product, now heading the unit. The first iPhones had begun reaching consumers in June 2007, so he worked on the company’s crucial first mobile app. Though some predicted that the shift to mobile would put Facebook out of business, it turned out that the scrolling News Feed was perfect for smartphones, and once the company agreed to permit ads into News Feed, the bumpy transition succeeded. Cox also oversaw the introduction in early 2009 of a risky, major redesign of News Feed, too, which instituted real-time updating and put headlines into more of a first-person format, replacing the original, impersonal, news-ticker style: “Mark became friends with Chris,” or “Ruchi uploaded and tagged a photo.”

In December 2010 Cox and Vichit-Vadakan—by now a filmmaker—got engaged in a traditional ceremony in Thailand. The two then got married, in July 2011, near the cabin they were then living in on a five-acre plot of land in the La Honda, a bucolic area of rolling hills west of Palo Alto. The couple’s mutual mentor, Mancall, played a ritual role in the Thai ceremony and officiated at the wedding. (Cox’s high school Great Books teacher, Landor, was among the guests in California.)

To prepare the La Honda property for the affair, Cox hired a visual artist, Drew Bennett, who has been a close friend since high school.

“Chris was in all the advanced classes,” recalls Bennett, “so we were never in a class together.” But Cox had taught him to play guitar back then, with Bennett bartering for the lessons with his paintings—an indelible experience for Bennett.

“As teenagers, we’d joke around and do low-brow American stuff,” Bennett says. “But to spend an hour or two a week where he was teaching me triads, scales, structure, technique, music theory all at once—that was a much more intimate, sharing experience than most high school boys are having.”

In 2007, after Bennett had moved to the Bay Area, Cox and Zuckerberg commissioned Bennett to do site-specific art installations for Facebook’s four-story University Ave headquarters. (Later, from 2012 to 2018, Bennett would be hired to head Facebook’s artist-in-residence program, which commissions artwork at all its offices.)

For the wedding, Bennett was asked to build rustic “infrastructure”—outdoor showers, composting toilets, and a set of sinks and changing rooms for guests who chose to camp on the property.

The “sculptural centerpiece,” though, was the dinner site, which Bennett designed collaboratively with Cox and Vichit-Vadakan. Though there were going to be 240 guests, the couple did not want there to be a table 1, table 5, or table 12, with an accompanying sense of hierarchy.

So Bennett created one huge, triangular, tiered, picnic table, built into the gentle slope of a hill. Each edge ran 200 feet, with a gap in the base, so guests could enter the triangle and sit on both sides of the table.

“Chris and Visra sat at top of the hill, at the apex of the triangle,” Bennett explains. “The idea was that they could make eye contact with every guest at their wedding, and every guest at the wedding felt that they were sitting at the same table.”

Facebook gets a lot of bad publicity

By 2016, Cox was among a handful of the longest tenured Facebook employees. Several friends remember him as having talked by then about a possible next chapter. (Zuckerberg said Cox had discussed that subject with him, too, in his Facebook post accompanying Cox’s departure last month.) But that November, everything changed.

That month, the United States elected a president unlike any in memory. He was not just adept at using social media—Twitter, mainly—but seemed to many like a toxic byproduct of the whole genre. Whether by design or happenstance, his rhetoric seemed tailor made to provoke the “engagement” that social media metrics and algorithms crave and amplify. His statements were frequently inaccurate, sensational, outrageous, angry, and pugilistic, sometimes tip-toeing along the blurry frontiers of hate speech and racism.

Soon after the election it became clear that Russian government agents had opened phony accounts on Facebook and other social media sites in an effort to propagate messages favoring Trump’s election. Financially motivated spammers had also spread fake news across the site—often pro-Trump. Though it appears unlikely that the Russian activity could have actually tipped the election outcome—Facebook has maintained that their posts composed only “four-thousandths of one percent” of the 33 trillion political messages posted during the election—the results were close, so anything was possible.

Other, longer-standing critiques of Facebook—like the notion that News Feed’s invisible algorithms were creating “filter bubbles” that polarize users’ politics without them realizing it—suddenly gained greater traction than in the past. Then the Cambridge Analytica scandal erupted. The pro-Trump consulting firm had obtained the data of 83 million Facebook users, without their knowledge, for use in crafting hyper-targeted political ads. The revelation incited still more outrage, including inquiries by Congress and the British Parliament.

“When Facebook began to get a lot of bad publicity,” Cox’s father says, “I think that probably locked Chris in tighter at Facebook,” making him stay longer than he might have. “He thrives on that kind of challenge.”

“You get a real sense of people when things get tough,” says Caryn Marooney, Facebook’s vice president of communications, who announced in February that she’d be leaving after eight years. “You can freak out. You can blame other people. You can put your hands up and walk away. Or you can try to figure out what the biggest issues are and take them on.” The last is the hardest, she notes, because “people may criticize you even more. That’s what I saw Chris do.”

Cox does not buy the “filter bubble” critique—the notion that Facebook polarizes political discourse. He believes that sound academic research, like that of Pabló Barberá of New York University, establishes that Facebook actually widens the breadth of ideas its users are exposed to, at least when compared to other media, like talk radio and cable news. (Barberá posits that Facebook users’ friends typically include “weak ties”—like relatives or people known from high school—who don’t run in their current circles, and expose them to views at odds with their own.)

Cox also feels, according to one person familiar with his thinking, that at least part of the reason the press has turned so hostile toward Facebook is that the company is eating the media’s lunch in terms of advertising sales—a not uncommon perspective at Facebook.

At the same time, Cox recognized that some criticisms of Facebook were dead-on, and he set about addressing the company’s failings. He formed teams aimed at purging various kinds of misinformation from the site, securing election integrity, and exploring the special challenges of “critical countries,” like Myanmar and Cameroon, where ethnic violence and civil strife posed unique challenges.

He also told David Ginsberg, a newly arrived Facebook research director in 2017, to read the writings of, and reach out to, Tristan Harris, the technological ethicist, to understand and address his concerns about social media, Ginsberg recalls. Harris, who co-founded the Center for Humane Technology, has criticized technology companies for using behavior modification techniques to induce users into spending unhealthy stretches of time on their products, to the detriment of their psychic well-being.

Tessa Lyons, a Facebook product manager, worked on a team Cox set up to fight misinformation. She says he pushed her group to “engage deeply with academics, other tech companies, fact-checkers, media literacy organizations, and civil society groups around the world, getting their expertise and feedback—not just on our solutions and strategies, but on emerging problems that might not be manifesting yet but could be coming around the corner.”

Cox was a detail guy. “He wanted to see examples of the types of posts, articles, videos that we were seeing,” Lyons says. “We’d send him a document the night before a meeting with examples, progress, and plans. He’d come back that same night: ‘Why did this solution not work? Why is it going to take this long? Is that true across Instagram, and are our solutions going to be effective for them as well?’”

By the time people reached the conference room, she says, they could plow right into the details.

“He was not going to waste time,” says Marooney. If 10 minutes was all that was needed, that’s all it took, she says. “You never left a Chris meeting not knowing what to do next.”

Facebook maintains that it has made meaningful progress in fighting misinformation since 2016, citing the findings of four independent studies. It has changed its policies on political ads, and become more transparent. And it has added about 15,000 contract employees around the world to moderate allegations of hate speech flagged either by users or artificial intelligence.

But the cat-and-mouse game is perpetual. After this week’s deadly Easter church and hotel bombings in Sri Lanka, the government there preemptively blocked Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, and other social media sites altogether for fear that misinformation and hate speech on the platforms would worsen the crisis. And earlier this month The New York Times reported that Facebook was being overwhelmed by false posts and hate speech in India in the run-up to elections there. (Facebook has more than 340 million users in India, speaking more than a dozen languages.) Later that same day, Facebook took down 500 inauthentic Indian accounts, the company said.

In response to Tristan Harris’s criticisms, the company announced major changes to its News Feed algorithm in January 2018, designed, it said, to promote the “well-being” of users. The main shift was that it gave greater priority to family and friends’ posts over news posts. (The switch infuriated media publishers, who saw their referrals drop precipitously.) The company also implemented tools enabling users to track and limit the hours they spend on Facebook or sister sites Instagram, WhatsApp, and Messenger. (Critics derided those reforms as window-dressing. Harris did not respond to inquiries.)

The abuses that have occurred on Facebook’s site in Myanmar are among the most disturbing. In August 2018, both the UN Human Rights Council and Reuters issued detailed reports criticizing Facebook for having been “slow and ineffective,” in the HRC’s words, to police hate speech that was furthering a ruthless campaign against the Rohingya minority and other Muslims. (That month, Facebook did take the unprecedented step of banning several high-level military officials from the site, including the army’s commander in chief.)

Last December, former Facebook chief security officer Alex Stamos commented to me that the anti-Muslim hate speech in Myanmar was such a culturally intractable problem that he wondered if Facebook should just pull out. “You don’t make any money there,” he noted. “It’s all down side.”

I asked Cox about Stamos’s point.

He forcefully disagrees. When considering Facebook's role in any society in crisis, Cox says, the “macro-point” is this: “The binary decision—turn it on, turn it off—is nowhere near as nuanced as it needs to be when really understanding how a medium is being used in a crisis, both for good and for bad.”

To decide what to do, he says, you need to do what Facebook has done: “Go there. Talk to lots of people. Talk to NGOs who represent underserved communities especially. Try to really deeply understand how it’s being used.”

He then cites the research findings his people performed on the ground in Cameroon, a country now riven by civil strife, and where gruesome, violent images have sometimes been posted to the site.

“In the vast majority of cases these images weren’t being used to incite violence,” he says, “but were being used as an information service for helping people stay safe”—e.g., showing people, in real-time, where not to go.

“It’s almost like a telephone,” he continues. “If you shut off all the phone lines, is that a good or a bad thing in a crisis? That’s an issue that requires careful study.”

‘A new page in our product direction’

In January, Cox told Zuckerberg that he wasn’t getting joy from his job anymore, according to Cox’s mother, Mary Beth. Torn between his desire to move on and his loyalty to Zuckerberg and the company, Cox had been consulting his mentors—Mancall and his parents—about how to break the news that he wanted to go.

On March 14 he issued his official farewell post. Though it hinted at the disagreements, it was—well, as his high school teacher, Landor, would say—“magnanimous.”

“As Mark has outlined,” he wrote, “we are turning a new page in our product direction. . . This will be a big project and we will need leaders who are excited to see the new direction through.” He then named and praised the leaders who would succeed him, and thanked Zuckerberg for “creating this place, and for the chance to work beside a dear friend for 13 years.”

What’s next? He’s already “ramping things back up” in the music arena, starting to play with a reggae band and sitting in on some blues and jazz shows.

“I’ve received some interesting inquiries in the last two weeks,” he says, “but I’m going to take some time to think carefully about what’s next. I promised Visra I wouldn’t jump into anything for at least six months”

Mancall is urging him to affiliate with Stanford, starting or joining a think tank. “I do think these issues he’s working on are the most important of our age,” says Mancall.

Cox says a think tank holds some appeal.

But it’s hard to see that as his next big adventure. It doesn’t sound like it’s on the scale of traversing Patagonia, or playing keyboards with Fela Kuti’s son outside Lagos, or building a personalized daily newspaper for 2 billion people.

He needs to find something new that he almost can’t do.

See also:

Exclusive: Facebook ex-security chief: How ‘hypertargeting’ threatens democracy

Roger Parloff is a former editor-at-large at Fortune Magazine, and has been published in Yahoo Finance, Yahoo News, The New York Times, ProPublica, New York Magazine, and NewYorker.com, among others.