Faux Fuel: Can Chemistry Save Internal Combustion?

From the October 2021 issue of Car and Driver.

As the world's carmakers and governments turn toward electrification amid ever-dire climate predictions, some stakeholders are looking to keep gas-powered engines on the road without traditional petroleum-based fuel.

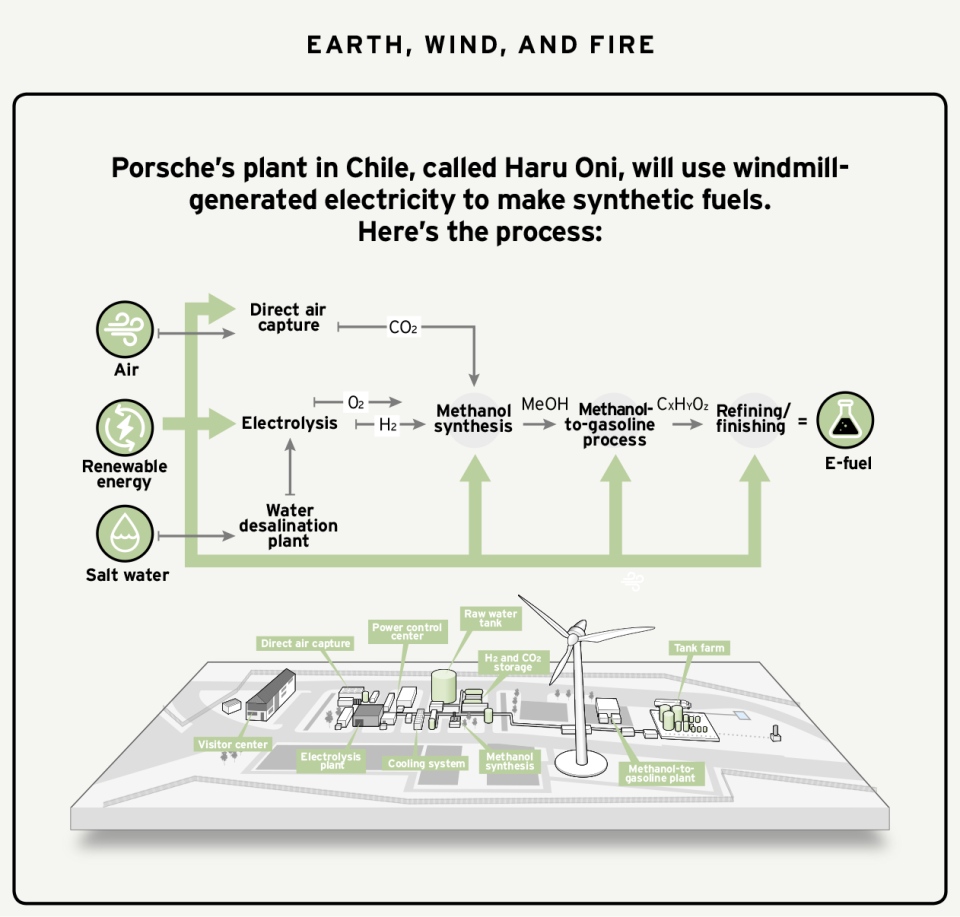

For the sake of the 911 (and plenty of other cars), Porsche, with partners that include Siemens Energy, has invested around $24 million in a large-scale commercial synfuels plant. The pilot plant, in Chile, could begin operating next year. BMW has also invested in a synfuels company, while McLaren is said to be readying a synfuel-powered prototype.

Porsche's goal is to produce a fuel by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity generated by a wind turbine. The hydrogen would then be combined with atmospheric carbon dioxide to create synthetic methanol, from which synthetic gasoline, diesel, and kerosene can be refined. Sounds clean, right? Just water and wind.

Well maybe, if that's how it's actually made, but historically, synthetic fuels have come from our old friend coal. The technology dates back to the 1920s, when German chemists Franz Fischer and Hans Tropsch developed a method to make liquid fuel by superheating coal. The Fischer-Tropsch process powered Germany through World War II and has been used for decades in countries with minimal oil reserves and large coal reserves, such as South Africa.

Today's spin on synfuels is that not only coal but also natural gas, biomass from crop waste, or CO2 itself—as in the Porsche plant—can be heated at temperatures exceeding 1800 degrees until it forms carbon-monoxide molecules. They're joined to hydrogen molecules in the same long hydrocarbon chains that make up the petroleum-derived fuel we know and, with some reservations, love.

Not everyone agrees that the technology is worth pursuing. Transport & Environment, a European lobbying group with an interest in electrified transportation, calls synfuels' environmental benefits "a mirage" and believes that lawmakers setting CO2 standards for new vehicles should remain focused on tailpipe emissions. Others have said synfuels are a product of the past. Downsides include the continued use of CO2-emitting carbon-rich fossil fuels, such as coal and natural gas, whose extraction harms the environment even before they're burned.

In 2012, Princeton University researchers projected that a complete transition to synfuels could eliminate up to 50 percent of vehicle greenhouse-gas emissions, but retrofitting U.S. refineries, according to the researchers, would cost more than $1 trillion and take 30 to 40 years.

Porsche is candid about the limitations of synthetic fuels. In announcing the plant, Porsche CEO Oliver Blume said: "Our goal is and remains electric mobility. This is the future. It must be emphasized that we do not see the use of e-fuels as an alternative, but as an addition to the all-electric drive."

You Might Also Like