Put another nickel in: How Cincinnati helped make jukeboxes cool

Wurlitzer is one of the oldest and most respected names in the music industry. The Rudolph Wurlitzer Co. began in Cincinnati in 1856 and went on to worldwide recognition for its pianos, theater organs and jukeboxes. For more than 130 years, Wurlitzer was, as the company slogan said, “The Name That Means Music to Millions.”

As with many Cincinnati institutions, Wurlitzer had German roots.

Founder Franz Rudolph Wurlitzer was born Jan. 30, 1831, in the Saxony village of Schöneck, now part of Germany. That region is known for its fine musical instruments, and for 400 years, generations of the Wurlitzer family have been instrument makers, notably of violins and lutes.

Rudolph’s father, Christian, bartered high-end musical instruments from local craftsmen to sell. After completing his studies, Rudolph expected to join the business, but his father planned to eventually hand it down to his youngest son, Constantin, who was just 6 years old at the time.

Frustrated, Rudolph borrowed 350 marks (about $80 then, or $3,000 today) from his Uncle Wilhelm and went to America in 1853 at the age of 22. Knowing very little English, he struggled to get work in Hoboken, New Jersey, then Philadelphia, before settling in Cincinnati, where he found camaraderie with fellow German immigrants.

'You're killing the game': Amazon delivery driver helps Chicago teen with tie before homecoming

Wurlitzer imported musical instruments from Germany

He got a job as a porter at Heidelbach, Seasongood & Co., a wholesale clothing and dry goods store at Third and Main streets, making $4 a week. (Some Wurlitzer histories call Heidelbach, Seasongood & Co. a banking firm, but the city directory shows it was a dry goods wholesaler.) To save money to repay his uncle, he was allowed to sleep in a crate in the store. He was soon promoted to bookkeeper at twice the salary.

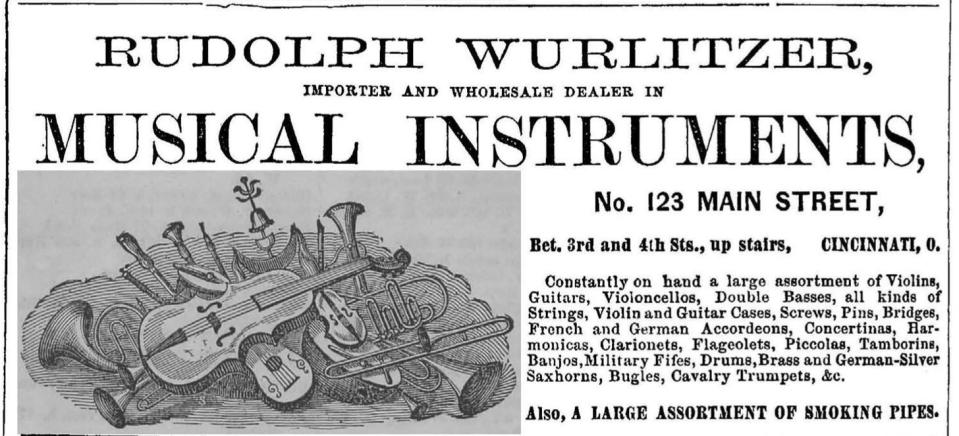

Rudolph did not play any musical instruments himself, but he loved music and knew about quality craftsmanship. He was astonished at the high prices for what he considered to be inferior instruments offered in the Cincinnati music stores, so he decided to import some from back home.

According to the Wurlitzer company history, in 1856 Rudolph invested $700 ($23,000 today) and asked his family to ship over a variety of instruments. (It is unclear how Rudolph obtained that much money.) When he offered the imported instruments to a local music shop, the owner was suspicious that they were stolen because Rudolph was charging so little. He refigured his costs, claiming he had made a mistake in calculating customs and transportation expenses, and the shop owner was assured Rudolph was honest. Rudolph pocketed $1,500 – a more than 200% profit.

He eliminated the middleman, importing the musical instruments directly from Germany to the shops. He opened a store on Main Street, between Third and Fourth, then in 1891 settled at 121 E. Fourth St., which was the company headquarters until moving it to Chicago in 1941.

Rudolph’s brothers, Anton and Constantin, joined him in America to work as clerks in his business. During the Civil War, Rudolph provided drums and bugles to the Union Army. Anton served with the Cleveland Zouave Cadets, but was wounded in the battle of Winchester, Virginia, in 1862 and was discharged.

Anton later became a partner in the company, which for a few years was called Rudolph Wurlitzer & Brother.

Meanwhile, Rudolph married Leonie Farny, the sister of famed Cincinnati artist Henry Farny, in 1868. Rudolph died Jan. 14, 1914, and is buried in Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati. His three sons – Howard, Rudolph Henry and Farny – carried on the family business, expanding it in new directions.

Wurlitzer branched out to selling Regina music boxes, coin-operated player pianos, automatic harps and Steinway pianos. It acquired the Melville Clark Piano Co. and the De Kleist Musical Instrument Manufacturing Co., plus their factories in DeKalb, Illinois, and North Tonawanda, New York, where Wurlitzer began making its own instruments.

Wurlitzer had retail stores in dozens of cities across the country, including on Disneyland’s Main Street.

Wurlitzer was the top name in jukeboxes

The Wurlitzer name really became known for the Mighty Wurlitzer theater organ, introduced in 1910 to accompany silent films, and its jukeboxes from the Big Band era of the 1930s and ’40s.

While the company didn't create jukeboxes, it certainly helped popularize them, as Wurlitzer was a generic term for jukebox.

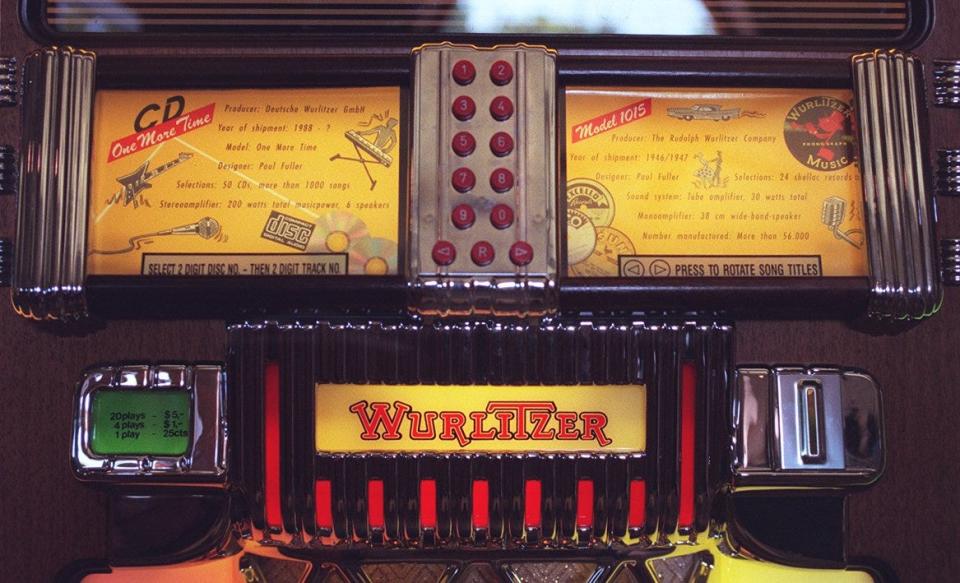

Its first jukebox, the Debutante model, was introduced in 1933, playing 78 rpm records before 45s became standard. Swiss-born designer Paul Fuller created Wurlitzer's iconic “lit-up” arched cabinet designs in the 1940s. The classic 1015 model from 1946, in art deco style with the rainbow bubble-arch, is considered the quintessential jukebox and is still highly coveted by collectors – selling for about $10,000 these days.

Jukeboxes were ubiquitous in bars and diners through the 1950s and are often used to symbolize the early rock ’n roll period. Jukebox record sales became the basis for Billboard magazine’s Hot 100 list. Like pinball and slot machines, they were also lucrative for the mob, a nickel at a time. The gangster Meyer Lansky reportedly controlled every Wurlitzer jukebox in New York.

But the music scene changed. Jukeboxes lost popularity in the mid-1960s, coinciding with the rise of FM radio. Japanese imports, such as Yamaha, cut into the piano and electric organ market.

Wurlitzer stopped making jukeboxes in America in 1974, but a subsidiary in Germany continued. Its retail stores closed. The last two in Cincinnati were taken over by Willis Music in 1982.

Wurlitzer’s piano manufacturing sold in 1988 to Cincinnati’s Baldwin Piano Co. (founded by D.H. Baldwin on Fourth Street in 1862), which was then bought by the Gibson Guitar Corp. in 2001. Gibson later acquired the Deutsche-Wurlitzer jukebox trademarks. Baldwin stopped using the Wurlitzer brand name on pianos in 2009.

Saving the Mighty Wurlitzer at the Albee Theater

One notable piece of Wurlitzer history remains in Cincinnati.

The RKO Albee Theater, the fanciest of the city’s movie palaces, opened at 12 E. Fifth St., opposite Fountain Square, on Dec. 24, 1927. Along with the marble staircases, brass fixtures and rococo detailing inside, the Albee featured a Mighty Wurlitzer organ, an Opus 1680, which cost $55,000 ($955,000 today).

Organists played music to accompany the action on the screen for silent movies. From the large organ console in the orchestra pit, the organist pressed keys that controlled air flow through 2,000 pipes located in the walls to make the sounds of 31 instruments, from whistles to tubas, violins and bass drums.

But shortly after the Albee opened, the sound era of movies began, and the Mighty Wurlitzer had little use.

In 1968, RKO sold off its theater organs. The Ohio Valley Chapter of the American Theater Organ Society bought the Albee’s Wurlitzer for $1 and relocated the organ to the Emery Theatre at 110 E. Central Parkway. It was moved again in 2009 to the Music Hall Ballroom, which is adorned with many fixtures from the long-gone Albee. The Friends of Music Hall presents two Mighty Wurlitzer concerts every year.

Sources: “Wurlitzer of Cincinnati: The Name That Means Music to Millions” by Mark Palkovic, “House of Wurlitzer” by Gary Rasmussen (AMICA Bulletin), “The Wurlitzer Story” by William Griess Jr., “Wurlitzer World of Music: 100 Years of Musical Achievement, 1856-1956,” Immigrant Entrepreneurship website, Friends of Music Hall, Mechanical Music Press, Wikipedia, Enquirer archives.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Made in Cincinnati: How Ohio helped make jukeboxes cool