What really caused the sriracha shortage? 2 friends and the epic breakup that left millions without their favorite hot sauce

On the day that the foundation of Craig Underwood’s business collapsed, he was on vacation—at the beach with his wife, daughters, and grandchildren in Hawaii.

It was November 2016, and the fourth-generation California farmer had just completed a perfect pepper harvest—another high point for a business, Underwood Ranches, that had grown exponentially over three decades on the strength of a single crop. As the sole supplier of the juicy red jalapeños for sriracha, Huy Fong Foods’ iconic fiery-red chili-garlic sauce, Underwood’s empire of peppers had spread from a 400-acre family farm in the 1980s to 3,000 acres across two counties outside Los Angeles.

Sriracha’s rise had by then become the stuff of business legend. That spicy, slightly sweet, good-on-everything sauce, in the instantly recognizable bottle with its white rooster emblem and bright green nozzle, was the brainchild of David Tran, who had first devised the recipe and sold the stuff in L.A. in 1980 as a Vietnamese refugee starting a new life for his family.

Tran’s business motto is “make product, and not profit,” but Huy Fong had become the No. 3 hot sauce brand in America—all as a private company, without selling even the smallest share to the country’s Big Food titans. At the time, Tran’s green-tipped bottles could be found in one in 10 American kitchens and on the International Space Station.

Sriracha’s success grew from the firm ground of Underwood and Tran’s business partnership: Underwood supplied all Huy Fong’s chilies, and Tran was Underwood Ranches’ only pepper buyer. By 2012, Tran had built a gleaming 650,000-square-foot factory less than two hours from Underwood’s Ventura County headquarters. On a tour of the site, he told Underwood that together they would fill it with chilies.

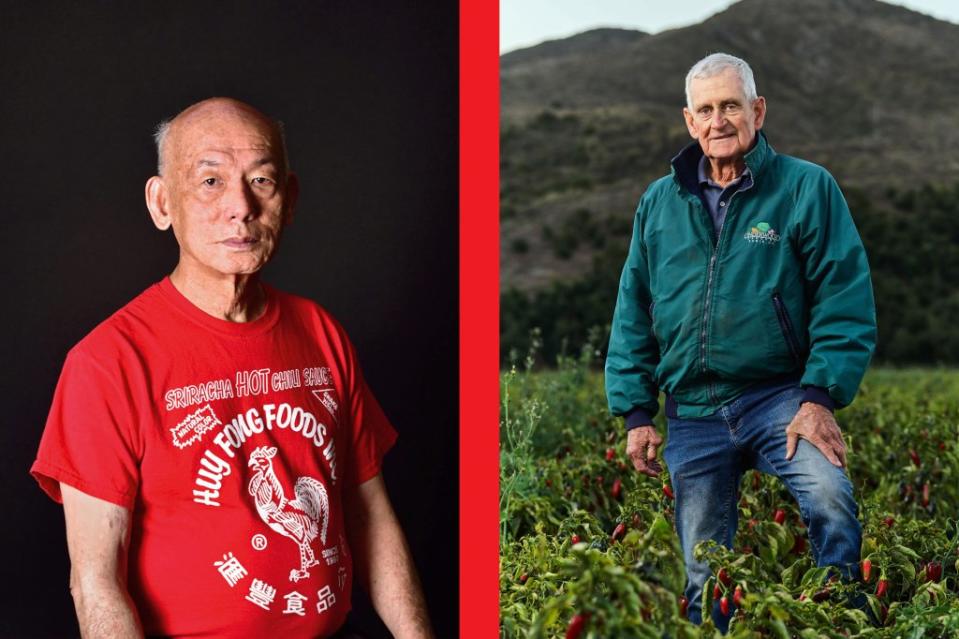

The two men came from different worlds, but they had a lot in common: Soft-spoken patriarchs with kind eyes and faces craggy with laugh lines, both had remained workaholics well into their seventies. Over the 28 years they’d been in business, the two had broken bread together with their wives, watched each other’s children grow up, stood together through hard times and business crises. They had even met up, with their families, to talk about succession.

Just days earlier, after the last truckload of the 2016 harvest had been delivered, Underwood and Tran had sat together and mapped out the 2017 growing season, and what Tran would pay in advance for the tens of millions of pounds of peppers Underwood promised him. As usual, the agreement was verbal, sealed with a nod and a handshake, not contracts or lawyers.

Then, on Nov. 10, at his vacation rental on Kauai, Underwood got a call with news that he could barely take in. His farm’s chief operating officer, Jim Roberts, told him that the relationship had ended, severed in one afternoon by an argument over payment for next season’s crop. Underwood Ranches and Huy Fong Foods would never do business together again.

“That’s one way to ruin a vacation,” Underwood now says ruefully.

The schism turned out to be even more catastrophic than either side could have imagined. It left Tran without the peppers he needed to meet the ever-growing demand for his sriracha. Since he lost Underwood’s chilies, his massive factory in Irwindale, Calif., has operated sporadically, at a fraction of its capacity. For the first year after the split, Huy Fong got by on stockpiled mash and Mexican chilies, which were cheap because of a glut. But supply has often been spotty since then: In the first half of 2023, Huy Fong had no chilies at all.

Underwood, meanwhile, faced financial ruin: The vast swaths of land that he had purchased or leased to grow jalapeños couldn’t be planted without a buyer. He was locked into 25-year leases on much of the land he had expanded into, and he didn’t have cash on hand to pay his own suppliers. He took out loans, sold some parcels, and laid off 45 workers.

Both businesses lost millions. The two men became bitter enemies—and they offer sharply contrasting accounts of what went wrong.

At first, Underwood recalls, he was confused and hurt. “We were trying to figure out what the hell’s going on,” he tells me when I visit his offices in Camarillo, Calif., in December. “Because we were really vulnerable, both in the percentage of our business that he commanded—and I guess our belief that we were going to have a long-term relationship.” But he soon became convinced, Underwood tells me, that Tran’s intentions were bad, and had been for some time. “Basically, he really was out to destroy me,” he says. “He didn’t give a damn about me or our family or all that we’d done together.”

Over at Huy Fong, feelings were similarly raw. Tran felt betrayed, and blindsided by accusations that he had been underhanded. For most of three decades, he had remained loyal to Underwood as his only pepper producer, and each year he had handed over millions on the promise of a harvest, a gesture that he saw as an act of faith. Now all that trust had collapsed in a petty argument over money.

Tran has come to believe that Underwood was trying to drive him to bankruptcy, then steal his sauce business. “I helped him because he grew chili for me,” he says. “He made money, he owned land. But it is not enough. He wanted to take over my business.” It felt like being “stabbed in the back,” adds Donna Lam, Tran’s sister-in-law and executive operations officer.

Tran came to believe that Underwood was trying to bankrupt him: “He made money, he owned land. But it is not enough. He wanted to take over my business.”

Following the 2016 blowup, months of tense negotiations between the two parties to try to resuscitate the business arrangement failed. In 2017, Huy Fong Foods sued to recover an overpayment for the 2016 harvest, and Underwood Ranches countersued, alleging fraud and breach of contract. A jury found in the farmer’s favor, awarding him $13.3 million in compensatory damages and $10 million in punitive damages. It also found that Huy Fong had overpaid Underwood $1.4 million for the 2016 growing season, and ordered Underwood Ranches to reimburse that amount.

But the legal resolution didn’t ease either company’s struggles. Meanwhile, the fallout from the breakup continues to leave sriracha lovers scrambling to get their fix. Those once-ubiquitous bottles became scarce and at times disappeared from supermarket shelves. Headlines about the Great Sriracha Shortage led to stockpiling, and the sauce started selling on the online resale market for up to $80 a bottle. Dozens of copycat srirachas have thrived amid the original’s scarcity, including versions from the likes of Tabasco and Roland, and generics from supermarket chains.

There’s a cruel irony to the predicament of Craig Underwood, who’s now 81, and David Tran, 78. One man with thousands of acres of pepper fields, but nobody to buy his peppers. Another with a massive pepper factory, and not enough peppers to keep it running. Meanwhile, an adoring fan base pines for the product the men made together, even as the two remain estranged—victims, perhaps, of their own runaway success.

What makes sriracha special? Tran’s sauce is a simple uncooked and unfermented puree, made by grinding together fresh red jalapeños, sugar, garlic, vinegar, and two preservatives. And it truly is good on everything, food writer and chili sauce aficionado Matt Gross says: “It’s just a really great, balanced blend, and it adapts well. It’s not too spicy. It’s not too garlicky. It’s not too vinegary.”

Tran’s striking product design helps: The iconography of the rooster picture (to commemorate the year of Tran’s birth, 1945, in the Chinese astrological calendar) and that jaunty green nozzle make a Huy Fong sriracha bottle hard to miss. “It is a gorgeous, gorgeous object,” Gross says.

Though Tran loosely based his sauce on a Thai fermented dip for eggs and seafood, and named it for the coastal Thai town of Si Racha, Huy Fong’s sriracha is quite different—thicker and less sweet. Still, its being named for a town meant that “sriracha” couldn’t be trademarked in the U.S.—a fact that became significant when other brands began using the product name.

Tran’s timing for launching sriracha was impeccable; it arrived just as American tastes were beginning to broaden and become more adventurous. In 1980, when Tran started bottling his sauce in an industrial space he rented near Los Angeles’ Chinatown, America was not yet a place of ghost-pepper-eating contests or tattooed hipster chefs touting bespoke chili-sauce brands. “I wasn’t thinking of selling it mainstream to the Americans,” he explained in 2013 for a Vietnamese American oral history project at the University of California, Irvine. “I was going to sell it to Chinese or Vietnamese.”

Huy Fong made three chili sauces, but it was sriracha that really caught on, first in California’s immigrant communities, and then on a much vaster scale. Kara Nielsen, a food trends researcher, remembers first encountering the sauce when she was a pastry chef in the 1990s at a farm-to-table restaurant in Berkeley. Although it wasn’t offered to customers, there was always a bottle of the “rooster sauce” on the table during staff meals, she says: “It was used by the Latino and Asian cooks to basically add chili heat to anything.” Within a few years, she says, foodies had taken to the product, eagerly squirting it on their Vietnamese banh mi sandwiches in San Francisco’s Tenderloin district.

As demand ramped up, Tran’s big challenge was finding a stable source of fresh, red jalapeños—the freshness being, in his view, the key to his sauce’s flavor. At first he relied upon local supermarkets and wholesalers at L.A.’s Central Market. But the supply was inconsistent and the timing was tricky: Most jalapeños are sold when they’re crisp and green, but Tran’s sauce requires the sweeter, less-grassy version of the fruit, after it ripens to red—but before it overripens and becomes soft. That makes it a finicky product for farmers to grow and transport.

The answer to Tran’s conundrum came in a letter. In nearby Ventura County, Craig Underwood was facing headwinds keeping his family farm going. California’s conventional vegetable farming landscape was changing, and Underwood had pivoted to growing baby vegetables and salad greens. The advent of “baby-cut” carrots (larger carrots cut to snackable size) threatened that business too. In 1988, a seed supplier mentioned to Underwood that he had heard about a guy pounding the pavement for peppers for chili sauce in L.A., Underwood recalls: “I wrote a letter to David and said, ‘Would you like me to grow some peppers?’ ”

Tran contracted Underwood to grow 50 acres—and so began a lucrative relationship for both men. Over the next three decades, they became, if not exactly close friends, at least friendly associates. When the city of Irwindale tried (unsuccessfully) to evict Tran’s new sauce factory in 2013, saying the chilies were releasing spicy fumes into the surrounding neighborhoods, Underwood testified on his behalf at a city council meeting.

Meanwhile, sriracha took off on a scale nobody could have predicted. As the American culinary palate has become more international, Huy Fong’s rooster sauce has grown ubiquitous. Huy Fong remained an independent company, turning down offers to buy or invest from large food corporations, and has never spent a penny on advertising. But the brand spread rapidly by word of mouth, creating a fandom that has made the sauce into a kind of identity statement, with festivals, online videos, rooster-branded T-shirts, and streetwear brand collabs. Huy Fong doesn’t disclose revenue figures, but according to the market research firm IBISWorld it had sales of $131 million in 2020.

Sriracha has achieved the rare feat of creating its own category of culinary product, a craveable flavor that has shown up in mass-marketed foods from McDonald’s chicken sandwiches to Doritos’ Screamin’ Sriracha chips, and in the kitchens of Michelin-starred chefs. “The lure of Asian authenticity is part of the appeal,” the New York Times food writer John T. Edge observed in 2009, describing the “polyglot purée” beloved by chefs including Jean-Georges Vongerichten.

The exclusive, symbiotic relationship that Huy Fong Foods and Underwood Ranches developed was “highly unusual in the processing business,” Underwood says in a 2013 documentary. “But as long as they’re selling more product, we have to be growing it for them. It’s a big job. A huge job.”

That film, Sriracha, now feels like a kind of time capsule—a snapshot of the two businessmen flying closer and closer to the sun. The relationship of the sauce maker and the farmer was the emotional heart of the film, and its director, Griffin Hammond, remembers finding the men’s relationship “beautiful”: “They both spoke so fondly of each other,” he tells me.

How did that beautiful relationship fall apart so quickly and brutally? It’s a question both Underwood and Tran still puzzle over, and sriracha fans speculate about online. But the basic story is laid out, starkly, in court papers from the lawsuit and countersuit that followed the imbroglio.

As Huy Fong’s business grew, so too did Tran’s need for massive quantities of chilies, and Underwood kept increasing the farm’s pepper fields, reducing his other crops. To reassure the grower that he wouldn’t be financially wiped out if one year’s pepper crop failed, the companies agreed in 2008 to switch to a system of acreage instead of volume, with Huy Fong assuming the risk by prepaying at the beginning of the growing season to cover the costs of seeds, equipment, and labor. Working this way, the two companies kept ramping up yields and production, to a height of 100 million pounds of peppers in 2015.

That's the year that trust between the two companies began to erode. Tran started a separate company, ChiliCo, to buy and sell chili peppers. Underwood didn’t want to work with ChiliCo because he feared it wouldn’t have the assets to guarantee payments. To make matters worse, Underwood says, Tran and Lam made several failed attempts to hire Roberts, his COO, to work for ChiliCo. (Lam says the offers to Roberts were always intended to supplement his income at Underwood Ranches, and not to poach him.)

Things came to a head that terrible afternoon in November 2016. Recollections differ, but what’s agreed upon is this: On Nov. 9, Roberts drove over to Huy Fong’s factory at Tran’s request, to look at some equipment. Tran and Lam called Roberts into his office for a conversation, which turned contentious.

They disagreed about what price Huy Fong should prepay for next season’s peppers, and whether Tran could get those jalapeños cheaper from overseas; whether Roberts should accept Tran’s offer to work for him; and whether Huy Fong had overpaid for the 2016 season.

The row raged on and on. Things were said that couldn’t be taken back. And by the time Roberts left a few hours later, a 28-year business relationship was effectively over.

Seven years after the rift, both companies are creaking along, doing the best they can to move forward.

On a visit to Huy Fong’s factory in December, I watched bottles of sriracha being filled, sealed, topped with green nozzles, and packed into boxes to ship out to 26 nations. Workers, mostly dressed in sriracha-themed T-shirts from the factory swag shop, wore hairnets and masks but seemed accustomed to the throat-tickling capsaicin fumes in the air.

Ominously, there were no unprocessed chilies on hand—none had come in lately. Part of the problem, Tran and Lam explain, is quality control: Freshness is what makes Huy Fong’s sauce better than the competition, and Tran says he often has had to turn away truckloads of that delicate red jalapeño because they didn’t make the journey from suppliers intact, were not properly refrigerated, or were picked when green.

Even with the disruptions in production caused by the ongoing chili supply crisis, Huy Fong hasn’t laid off any of its 115 employees, Lam tells me. “David paid out of his pocket to keep them there,” Lam says. “This is not the person that would cheat someone.”

Meanwhile, an hour and a half’s drive away, Underwood has launched his own chili sauce business. Underwood Ranches has a long way to go before it can put the disaster of the past few years behind it, but its fields are now planted with a mix of tomatoes for canning, potatoes, onions, Brussels sprouts, pumpkins, and other crops.

At Underwood’s processing facility in Camarillo, the ribbon mixers were churning out the last of a much smaller 2023 pepper harvest to make its own sriracha, known as Dragon Sriracha. It’s a brand that hasn’t broken through yet, but it’s growing—with a couple of big distribution deals on the horizon, Underwood says. He recently started shipping his sriracha to 24 Costco branches. However reluctantly, Tran’s onetime partner is joining his growing field of competitors.

The 800-pound gorilla in American hot sauce is, of course, Tabasco, which produces the nation’s most popular chili sauce. The McIlhenny Company, founded in 1868 on Louisiana’s Avery Island, launched its own sriracha in 2014. It wasn’t until 2022, however, that Tabasco’s version of Tran’s sauce really took off, and Lee Susen, McIlhenny’s chief sales and marketing officer, makes no bones about why: It was the “shelf voids” that the shortage of Huy Fong’s product left, he tells Fortune.

Tabasco wasn’t going to let Huy Fong’s crisis go to waste, so in September 2022 it launched the website srirachashortage.com. “LOOKING FOR SOMETHING?” it asks in large white block letters as a Tabasco sriracha bottle surges upward, looking at first just like a Huy Fong bottle (though with a nozzle that’s olive green rather than bright green).

Previously the challenge Tabasco faced with its sriracha, Susen says, was that “most consumers saw sriracha as a brand. They didn’t recognize it as a product type.” But when Huy Fong’s iconic bottles disappeared and were replaced by various other srirachas, that began to change: It became just another pantry staple. The brand loyalty that had been Huy Fong’s economic “moat”—business parlance for a competitive advantage one company holds in its sector—started to erode.

And that’s when the biggest hot sauce brand in America swooped in and took the crown. Tabasco had the bestselling sriracha in the country for the second half of 2023, according to NielsenIQ. Sriracha, the product, is more popular than ever—it’s now in one in three U.S. kitchens, according to market research firm Circana—but most of it is not Huy Fong’s. “It’s a very exciting time to be in the hot sauce business,” Susen says. “And certainly the sriracha business.”

Tabasco’s win is Huy Fong’s loss. And it’s an epic comedown for a great American brand, an ignoble ending to a storied American business partnership between a hardworking Vietnamese refugee and a salt-of-the-earth California farmer.

Maybe Craig Underwood and David Tran were, on some level, victims of their own success? “We hooked onto that wagon and it really took off,” Underwood says now. “And we never could have predicted it when we started.”

Indeed, when Tran was grinding chili sauce in his kitchen and Underwood was farming baby carrots, neither could have imagined that they’d one day be managing hundreds of employees and making deals worth millions of dollars. In retrospect, Underwood says, he wishes they had built in more legal safeguards to protect their businesses from the beginning. He wonders whether he should have spread out his risk, instead of treating the arrangement between the two companies as a partnership. He wishes sometimes that he had sold his pepper production operations to Huy Fong Foods (an offer he made at one point) and started afresh.

Both Tran and Underwood brought great qualities to the partnership: grit, inventiveness, passion, ambition. But the skills and disposition necessary to make a startup a success are quite different from the competencies that people running large companies need. That’s one reason many founders end up selling or taking investments, says Maurice Schweitzer, a professor of operations, information, decisions, and management at the Wharton School. Doing so can feel like “selling out,” but bringing in a more experienced partner can also be stabilizing.

“Nobody can understand what it was like,” says Underwood. “In this, everybody turned out to be a loser.”

It’s impossible to know for sure, but a change in ownership structure might have made all the difference, Schweitzer says. Human relationships are fraught, and almost always include an element of competitiveness. Unchecked, that competitiveness can grow like a weed and take over, especially when a business is expanding rapidly: “There’s going to be some point of friction; there’s going to be some miscommunication,” Schweitzer says. “We need some mechanism to correct that and put it back on track.”

For instance, when a dramatic leadership crisis erupted last November at the AI startup OpenAI, Microsoft’s role as a major investor helped force a quick resolution. “With Microsoft, there’s a grownup in the room,” Schweitzer says. “They can keep their eye on the ball.”

But with Huy Fong and Underwood Ranches, Schweitzer points out, “it’s just two people left on their own … There isn’t, like, some arbitrator or banker; there wasn’t a third party to bring them together.”

A broken business deal doesn’t quite rise to the level of tragedy. But there is something very sad about how David Tran and Craig Underwood were willing to walk away from each other, leaving all that they’d built in peril and untold millions on the table. Once their trust was broken, their enmity grew stronger even than their desire to succeed.

With so much at stake and so much opportunity remaining, I ask each man: Would they ever come back together?

Absolutely not, Tran tells me. “I need chili, but a guy like that? Why?” he says. “Without his chili, yeah, we make less money. But no.” Lam says her family has tried to put the affair behind them. “At the end it just got really messy,” she says. “And David and I, we don’t want to talk about it, because what’s done, it’s done. It doesn’t matter … What’s lost is lost. And that’s the sad part about it. We’re not going to think about the past. We need to think about the future.”

Underwood is similarly adamant when I ask whether he’d ever work with Huy Fong again. “Not with David,” he says. “If somebody else took over, purchased Huy Fong Foods, yeah, we’d certainly want to do business. But not with David.”

Looking back is hard for Underwood, too, he tells me, and he sometimes wonders how he got through those first few years after the breakup. “Nobody can understand what it was like to go through that whole thing,” he says. “I mean, it was hell.”

Of course there’s one person who probably could understand it. And seven years later, that’s one thing the former partners still have in common, as Underwood acknowledges: “In this,” he says, “everybody turned out to be a loser.”

—Jasper Chapman contributed reporting to this story.

This article appears in the February/March 2024 issue of Fortune with the headline "Hot Mess."

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com