Stubborn Germany is weakening Europe’s most powerful economy

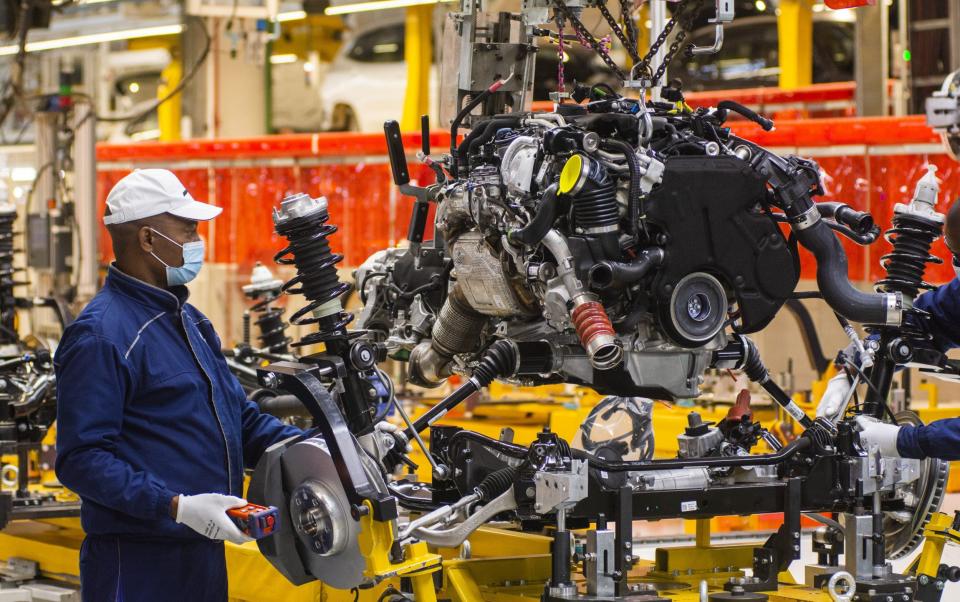

It was one of the great German inventions. It was the foundation of the country’s economic success. And it still accounts for more than a million jobs, sustains some of its largest companies, and embodies much of its national as well as economic identity.

In fairness, no country has more at stake in the survival of the internal combustion engine than Germany nor as much to lose from its replacement by batteries to power our cars. And it is perfectly understandable that it is fighting a fierce rearguard action within the European Union to keep it for as long as possible.

In reality, Germany’s big bet on petrol will turn into an epic failure of industrial policy.

Sure, we can all work out why it wants to hang on to it. The trouble is, it means it will mean it gets left behind by smarter competitors; it will hold up investment in new industries; and it will entrench the power of vested interests that are inevitably opposed to change.

In truth, clinging onto old technologies never works – and Germany will only end up weakening what remains the continent’s most powerful economy.

The rest of the world might be competing furiously on green energies, on subsidies for battery plants, and on building the charging infrastructure that will make the traditional petrol station a historical relic, but Germany, it seems, has decided that the internal combustion engine is the future.

The EU had been planning to ban the sale of new petrol-driven cars by 2035, the same year that they will be phased out in the United States, Britain, and many other major economies.

Over the last few weeks, however, Germany had been putting up stiff resistance to that, demanding that the ban be delayed, or include an exception for synthetic fuels. Last week Austria joined its larger neighbour’s cause, with the Chancellor Karl Nehammer committing to fight the ban. It remains to be seen what happens over the next few weeks.

One point is surely clear, however. Within the EU, Germany generally gets its own way. We can expect the ban to be watered down to insignificance. While the rest of the world focuses on switching to electric, with hydrogen as a potential back-up if the technology can be made to work, Germany will double down on diesel and petrol instead.

Of course, we can understand what the German industrial establishment is up to, even if it is, to put it mildly, a little surprising that the only major economy with the Greens as part of the governing coalition is fighting to preserve fossil fuels.

The petrol engine is crucial to the prosperity of the German economy. It accounts for a million jobs directly, once parts suppliers are included, and many more are dependent on the wealth it creates.

It generates $120bn (£99bn) in exports every year. And it delivers the profits and growth the country needs to keep expanding. In many countries, the car industry is important, but in Germany it is crucial.

Sure, Volkswagen, BMW and Mercedes are all pouring billions in investment into electric cars, and may hope to emerge as leaders eventually. For now, however, they are still a long way behind.

In the last quarter of 2022, VW had a 4pc share of the global markets for EVs, a third of Tesla on 12pc, and a fifth of China’s BYD, on 20pc. Without petrol and diesel, Germany is not a world leader in autos anymore. If that is not worth a fight to hang onto, it is hard to know what is.

Here is the problem, however. Clinging onto old technologies is seldom a winning strategy. First, you inevitably get left behind by smarter competitors.

It is striking just how fast the marketplace for electric cars has changed in the last year alone, with BYD moving from a 5pc global share to 20pc, and Tesla dropping from 17pc to 12pc. This is a market still in rapid flux, as you would expect for what remains a relatively new technology.

There are still going to be lots of new companies entering the fray (although sadly probably not from the UK), but if you spend all your time defending your position in petrol cars you will inevitably be left out of that. By the time you catch up, the game will be over, and the market leaders will be impossible to dislodge.

Next, investment gets delayed. True, VW is spending a lot of money overhauling its product line, with more than €100bn invested in electric vehicles, but if it is still selling lots of diesel and petrol cars across Europe because the ban has been delayed, that will inevitably slow down.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, it will entrench the power of all the vested interests that are opposed to reform. If the UK often seems to be a health system with a country attached, Germany often appears to be an auto industry with a nation tacked on.

Its politics, culture, and economy are dominated by cars, and the longer it hangs on to the combustion engine, the harder it will be for it to ever change. At just the moment when Germany should be re-inventing its economy it is choosing to go backwards instead.

The UK is making a mess of the transition to EVs, but that is hardly critical since our auto industry is no longer vital to our prosperity, and hasn’t been for many years.

France is betting big that it can accelerate the transition, and smaller countries are carving out niches for their own manufacturers. But Germany is digging its heels in, and doing everything it can to make sure the petrol engine survives for as long as possible.

It is a huge gamble, and one that is not likely to succeed. Some time in the 2040s Germans might still be whizzing along the autobahns in their petrol-fuelled Mercs. But the rest of the world will have moved on. And clinging on to petrol will prove to be a huge strategic mistake for Europe’s largest economy.